When I was a toddler, my mother set up my playpen in front of the new black-and-white television in our St. Matthews home. I wonder how many other children’s first memories include Chief Counsel Joseph Welch asking U.S. Senator and communist-fearing demagogue Joseph McCarthy, “Have you no sense of decency, sir?”

Fast-forward 20 years to the spring of 1973. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas was speaking at the University of Louisville, and he hailed the newspaper for which I worked: “This community is blessed with the Courier-Journal, one of about 10 newspapers in the country in the days of Joe McCarthy that stood up for the rights of people.”

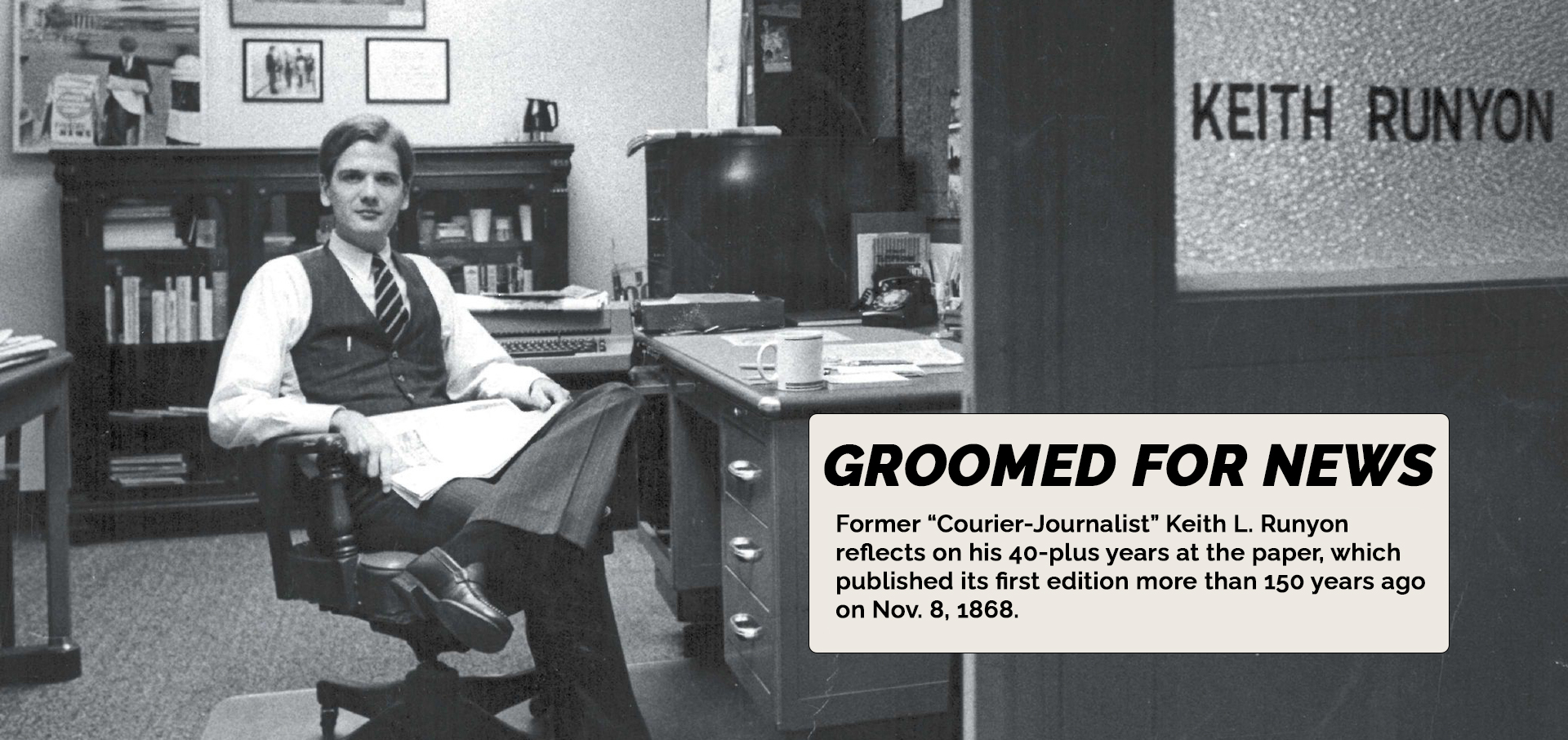

I came to work at the Courier-Journal in July 1969. The Vietnam War was raging and the newspaper was no stranger to the human impact. One of the obituary clerks was about to report for active duty in the Navy, and the paper needed a replacement. A longtime city editor had heard about me and suggested I meet the assistant managing editor, who was impressed that I already had experience writing obits at a newspaper in Evansville, Indiana. I was 18 and got the job, clearly the youngest person in the news operation.

Dec. 1 of that year remains vivid in my memory. That was the night of America’s first draft lottery since World War II. I was on the obit desk, but my priority was to answer the phone calls, mostly from young men who were my contemporaries and wanted to know what number they had been assigned. Every five or 10 minutes, one of our copy boys delivered a new strip of text from the Associated Press. As the numbers rolled in, so did the calls. It took some time before I learned that my own birthday — Oct. 3 — was number 244. While that was by no means safe, it was far better than the 243 other dates that preceded it.

Midway through the evening came a call from a guy who asked what his number was. “What’s your birthday?” I asked him.

“September 14th,” he answered.

I swallowed hard. “I’m really sorry,” I said. “You’re number one.”

He simply said, “Thanks.”

During the war, I would be handed AP stories listing Kentucky and southern Indiana military deaths. Generally we called the local funeral homes, which supplied information for death notices. But it was not always so with these young military victims. Sometimes days, or weeks, would pass before bodies were returned home. But my editors expected us to confirm that the AP reports were accurate. Sometimes I called the parents. One night, I placed a call to somewhere in rural Kentucky. A man answered and sounded confused as I explained why I was calling. “We don’t know anything about it,” he responded, choking back tears. Clearly the Defense Department had failed to do its duty if I was the messenger.

Journalists have to toughen up, and I did. On Thanksgiving 1969, I was writing obituaries when a report arrived of the death by starvation of a nine-year-old boy who lived on Eddy Alley in west Louisville. Robert Ellis’ tragic story led to major efforts to fight hunger and, in time, to the creation of the Dare to Care Food Bank. In later years I would be sent to other local calamities, as when, in November 1974, a house on South 22nd Street caught fire and three small children burned to death. Two others survived. I went with another reporter to interview them. Their home was in ruins and they huddled in the house of a next-door neighbor. Nine-year-old Darryl Knuckles remembered trying to wake his brothers, including four-year-old Elvin. “Something fell on Elvin – a lamp and something else – and I couldn’t wake him up. He was dead,” Darryl said.

Going to college was a sideline to my work at the newspaper. Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, I was due at the paper by 2 p.m., and work was pretty solid until about 9. By then, most of the day’s obits were written, and it was time for supper when the first edition went to press at about 8:45. Until I got off at 11, I would do my homework. It was good discipline. The fact that I had a job at the Courier-Journal was such sheer joy that I didn’t let the hard work bother me. In fact, I still say that even though I never took a journalism course after high school, I majored in “Courier-Journalism.”

Only months before I arrived, the staff had moved into a totally remodeled newsroom, the first major overhaul since the building at Sixth Street and Broadway opened in 1948. It became my second home. I worked in that building for 43 years, longer than the time in any home I’ve lived in. No wonder I still have dreams (and occasionally nightmares) set there. Philip Johnson, one of the great modern architects, declared in 1952 that the building looked “like a factory.” That’s what it was: a factory of news, entertainment and civic ambition. No structure symbolizes the city’s 20th-century greatness more than this one. Major figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt, Jimmy Carter, Muhammad Ali, astronaut John Glenn and Holocaust survivor Elie Weisel once strolled through the doors. It certainly belongs on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Bingham family owned the Courier-Journal and the Louisville Times (which ceased publication in 1987), and Barry Bingham Sr. resolved to create a living and breathing workspace for his newspapers and radio station (and, eventually, for WHAS-TV). Desks were modern, with side carrels for typewriters. The predominant colors were orange, tan and gray. In those days, the fourth floor was divided in half. The C-J editors and reporters were on the west side, the Louisville Times staff on the east. In the middle of the room was the copy desk, which was staffed around the clock for morning and evening news cycles. The air smelled of ink, paper and smoke from cigarettes and pipes. By about 5 in the afternoon, the newsroom’s roar was deafening. The combination of manual typewriters and ringing telephones required concentration skills that I cannot even imagine anymore.

An alcove contained a big Webster’s unabridged dictionary, with a tan leather cover and well-thumbed pages. We checked any word that seemed unusual, or possibly misspelled. A crusty chain-smoking reporter named Jean Howerton sat behind me, and every afternoon she poured something clear from a thermos into her tall glass of iced tea. As she drank, her cheeks got redder and redder, and her language saltier. My first big shock came the afternoon she exploded after slamming down the receiver. She yelled out a four-letter word that rhymes with “punt.” I was so innocent that, beyond “damn” and “hell,” I was ignorant of purple prose. I scurried over to the dictionary and looked it up. Jean saw me doing this and started to laugh. She yelled out to no one in particular: “Little Keith doesn’t know what c— means!”

In the summer of 1972, Louisville played host to a national political convention for the American Party. Along with another intern, I was assigned to cover the entire affair, spending long hours in hot and smoky Freedom Hall, where the delegates gathered. Over the course of a couple of days, I heard plenty of conspiracy theories and saw too many racist posters, bumper stickers and buttons. Those puzzled by Donald Trump’s supporters should have been with us in 1972.

Few people today realize how isolated Louisville was, as late as the 1970s, from newspapers produced outside the region. The Washington Post generally came one day late. The New York Times arrived by mail two days after it was published, though by about 1969, the Sunday edition was flown in and sold at a few spots in Louisville — Standiford Field, the Ramada Inn on Hurstbourne Lane and a seedy downtown porn shop euphemistically known as “Liberty News,” which was roughly where the entrance to the Hyatt parking garage is today. The fact that our local papers were essentially the only printed news sources placed a far greater burden on the editors here to provide a broad menu of information. Stories were generally shorter, but the array of information they offered was wide.

Barry Sr.’s shadow loomed over the city in the decades of his leadership at the Courier-Journal. For me, he became, in time, a respected mentor, a wise counselor and a friend. But when I first went to work at the paper, he seemed as unapproachable as the Wizard of Oz. And so he seemed in the spring of 1971, when I was invited down from the noisy fourth floor to the serene third, which was notable for its dark wood paneling, polished floors and thick carpeting. The outer office had a big vase of the daffodils Barry Sr. would bring into the office in big buckets, picked from his fields in Glenview.

I was ushered into his office, and before I knew it, Barry Sr. had jumped to his feet. At 65, he looked far younger. Unbeknownst to me and others who worked for him, he was preparing to turn over the reins of the publishing empire to Barry Jr. just three months later. Barry Sr. asked me all about myself. I mentioned that I was interested in going to law school, and he replied, “My father was a lawyer, but he found journalism to be far more satisfactory.” In a 1959 essay, Barry Sr. wrote: “Journalism…is the best of all jobs for those who have the temperament, the mental and physical toughness, and the sense of humor it requires.”

Barry Jr. was slender, with blond hair, bright eyes. The first time I saw him he wore a natty polka-dot necktie. He was always a willing listener, who expressed his delight by saying, “Don’t you love it?!?!” Many times over the years you’d pick up the phone and hear him on the other end, roaring about some news event. On Oaks Day, he hired the Churchill Downs bugler to ride the back elevators, stopping at each floor to toot the call to post.

If the Bingham family had a patriarch in Barry Sr., his wife, Mary Caperton Bingham, was its matriarch. She was often the true conscience behind the newspaper’s liberal editorial policies. Her charm was wrapped around an intellectual acuity and frankness that scared many at the newspaper. I would grow to not only appreciate her guidance but to look forward to it. Even if it included an acidic criticism.

By the summer of 1977, I was accepted to law school at U of L and, until mid-summer, was all set to go. But a vacancy opened up on the Louisville Times editorial staff, and I was able to sign up for a one-year stint. Being part of the editorial page would last for 35 years. I went ahead with my plan to attend law school, only I did it during the evening and avoided quitting the newspaper. Over the years, we wrote pleas for women, African-Americans, immigrants, the disabled, gays, the poor, the mentally ill, coal miners, farmers. We wrote about openness in government, fairness in taxes, equality in schools, affordable higher education, honest officials in public life. For me, some of these causes were far more than intellectual challenges. I passionately believed in racial equality, public education and libraries, and in honest government.

Every Monday and Thursday, at precisely 10 a.m., Barry Jr.’s secretary summoned us for our editorial conference. She rang a set of chimes that had once been used to call people to dinner, perhaps at the Bingham estate in Glenview. Her melodies were mysterious and different every time. But the message wasn’t mixed: It was time to get in your assigned seat. I sat at the foot of the table, directly opposite Barry Jr. When he sat down, the door was closed, and I don’t recall any of our meetings being interrupted. Former Mayor Charles Farnsley would regale folks by talking about this paneled inner sanctum, where neither phone nor radio interrupted the editorial board’s deliberations.

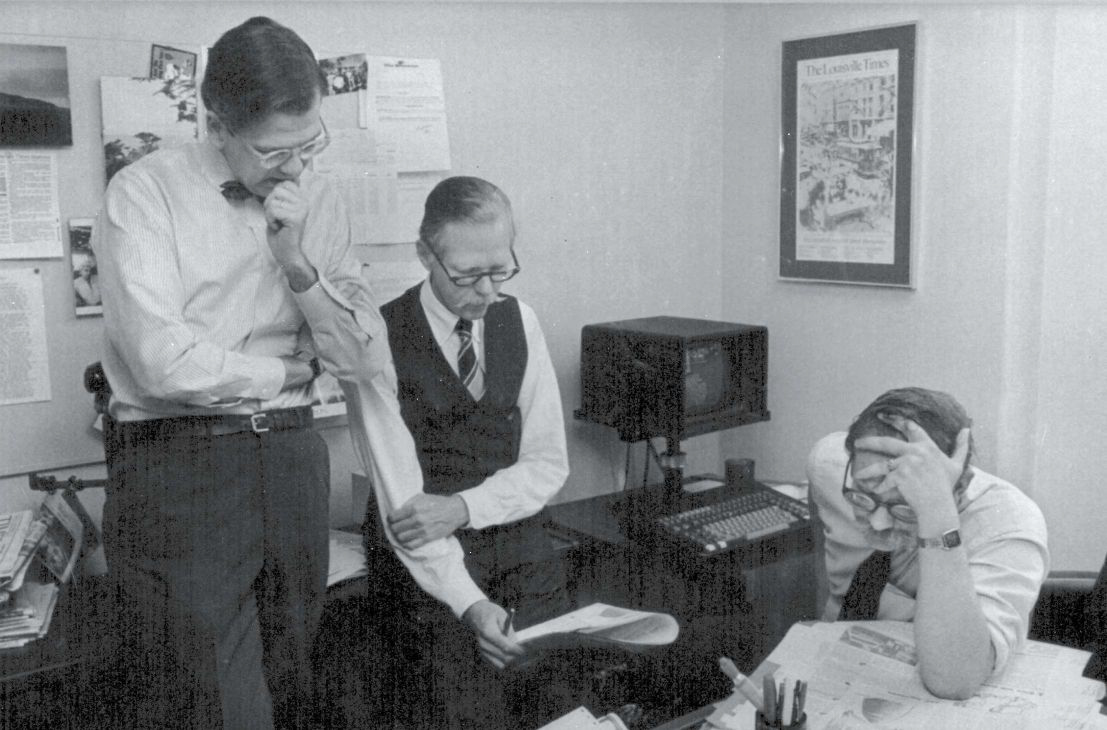

If the building was my second home, the staff became my second family. So many people left an impression. Probably the most notable of them all was David Hawpe, who came to work at the newspapers in 1969, just a few months before I did. He was born in Pikeville and moved to the city when he was four. I knew David’s mountain twang before I met him. While I was on the obit desk, he was a reporter in Hazard, Kentucky, and often he would call in stories for me to type. Among the most memorable was the night of the Hyden mine disaster, Dec. 30, 1970, a calamity that killed 38 men. He eventually became editor of the entire newspaper, and he presided over four Pulitzer Prizes: 1978 for coverage of the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire in Southgate, Kentucky; 1980 for international reporting in Cambodia; 1989 for reporting on the deadly bus crash in Carrollton, Kentucky; and 2005 for editorial cartooning.

There was also the time when one of our best city editors, Bill Cox, somehow arranged for Kentucky State Fair officials to let him ride a prize buffalo named Cody up the freight elevator and into the fourth-floor newsroom. Bill guided Cody straight into the office of executive editor Paul Janensch. Cody relieved himself on the rug. In time, that rug wound up in my office, and although there were no telltale signs of Cody’s deposit, I frequently shared the story with visitors.

I remember that the morning of April 3, 1974, was balmy, with a strange, high-level wind that seemed at odds with the sunshine. Late that afternoon, a tornado formed and was moving toward downtown. While most employees ran to the basement, a few of the photographers were up on the roof. The cyclone sounded like a locomotive. Larry Spitzer held his Nikon but was petrified. He froze. Bill Luster, another photographer, snapped: “Push the button, Larry! PUSH THE BUTTON, LARRY!!” Larry did. The one shot he got is immortal.

At Churchill Downs one Derby, aging cowboy movie star John Wayne, fresh off an Oscar win, approached Bill Luster, my diminutive colleague. The tall actor got down on his knees so Bill could get a close-up (it was great) and Wayne stuck out his hand, saying, “Howdy, little pardner!” Anther Derby, I remember the actor Gregory Peck sitting on the finish line huddled over the Racing Form. For the 100th Run for the Roses, in 1974, Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney threw their annual Derby Eve gala in Lexington, and the guest of honor was Princess Margaret (younger sister of Queen Elizabeth II), who was still married to Lord Snowdon at the time. I went to Rodes, bought a tuxedo and covered the party. I do not recall the exact circumstances, but somehow I wound up in a receiving line and met the princess. Before I knew it, I was told that she wanted me to be seated by her at dinner. When the orchestra began to play, the only polite thing to do was to ask her to dance. This was the spring that The Great Gatsby was in theaters, so together we did the Charleston.

Another friend and colleague, former New Yorker Betty Winston Bayé, once had an encounter with singer Rosemary Clooney. While she was interviewing the Kentucky-born star, Betty, who is African-American and was wearing black pants and a white linen top, was tapped on the shoulder by a stranger who asked her to get drinks for table 14. Clooney was so embarrassed.

The paper employed almost no black professionals when I started. Those who worked there either pushed a mop, cleaned the bathrooms or worked the back elevators. In my second summer, the city desk’s first black reporter, Joe Broadus, came on board. He and I were generally on the night shift, and we often ate dinner together. He was tall, skinny and very, very shy. It was a different story with Mervin Aubespin. He was a trailblazer who started his career in the art department. A Tuskegee graduate and former teacher at Central High School, his road to fame began in 1968, when the West End of Louisville erupted in riots not long after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Our white reporters had no sources in the West End; some didn’t even know the difference between Osage Avenue and Eddy Alley. That’s not to disparage them. Most of us who were white and lived in the East End were strangers west of 10th Street, where from time to time we boarded passenger trains at Union Station. Merv was recruited from the art department, handed a reporter’s notebook and went to the epicenter of the trouble. He sent dispatches back to the office from telephone booths. Eventually, the Binghams sent Merv to Columbia University.

Without question, a real perk of my job was meeting important people. And one of these encounters led to my saving Merv’s life. Henry Heimlich, the Cincinnati doctor who invented the life-saving technique called the Heimlich maneuver, met with a group of C-J staffers at the Old House Restaurant on Fifth Street, a popular spot for Courier-Journal lunch meetings. After the usual round of cocktails (the abstemious Barry Jr. always ordered something made with bitters), Dr. Heimlich, then a vigorous 55-year-old, enthusiastically talked about the benefits of saving lives by jabbing a victim’s diaphragm and pushing air up the windpipe. After dessert, we all stood up and began practicing on one another.

A few months later I was working the graveyard shift on Sunday with Merv. The cafeteria was closed, so generally we brought our own supper or went to the snack bar downstairs for junk food. Merv, as usual, brought a bag of pork rinds, and, true to his Louisiana roots, began to douse them with hot sauce. (He kept a bottle on his desk.) A little while later, I heard a strange sound coming from him at his desk across the room. His complexion had turned gray, and he was wheezing badly. I rushed to him, putting both arms around his tummy. I gave him a few stiff punches and — pop! — the offending pork rind flew out of his mouth and across the room.

Unlike his father, Barry Jr. was not to age gracefully in the publisher’s chair. In January 1986, having just turned 53, Barry Sr. put all the family companies on the market, effectively throwing his son out of work in his prime. For years, internal strife within the Bingham family had roiled the workplace and was the topic of much talk and concern in the city. Finally, Barry Sr. said, “Enough.”

As so often happened in those days, the announcement came through memos posted on the newspapers’ bulletin boards. As I walked into the building, I ran into Johnny Maupin, the chief artist, who was furiously puffing on his cigarette. “He’s done it!” Johnny cried, with tears in his eyes.

“Done what?” I asked.

“The old man’s put the papers up for sale!”

Over the years I came to see some of the wisdom in Barry Sr.’s decision. All across America, the great privately owned publications were falling one by one into the hands of corporations. At the time, the Louisville papers were sold to the Gannett Corp. for $300 million, then the largest amount ever paid for American newspapers.

My identification with the Courier-Journal is now, almost 50 years after I went to work there, unbreakable. Frequently, I am asked what I think of the newspaper today, or what I think could have happened to make things turn out differently. I’m afraid I just don’t know. What happened between 1986 and today happened slowly. There were periodic invasions by corporate “geniuses” who would never have been hired by the Binghams. And the bean counters kept cutting back. Now, newspaper executives believe that producing a local paper is the same whether you are in Phoenix, Fort Collins, Rochester, Indianapolis, Nashville, Pensacola or Louisville. But one paradigm doesn’t fit all. The beauty of local newspapers as we once knew them was that they translated the world and the nation to the perspective of a given community. The newspaper in Louisville should be fundamentally different from a newspaper in any other place.

My last encounter with Barry Sr. came just a short time before his slow and painful death of brain cancer in August 1988. I came with my wife, Meme, and our son, Lee (then only about seven months old), to the “Little House” on the Bingham estate, where he and wife Mary Bingham had lived in retirement. Barry Sr. was in a bedroom that had been outfitted like a hospital suite. He was in a white gown, one of his legs extended on a lift, and his face was badly disfigured by a swollen tongue that made speaking impossible. His head of gleaming white hair had given way to baldness. Still, I attempted a conversation, and with his famous blue eyes and his nodding chin, he made clear that he understood what I was saying. I promised him that we on the editorial staff would continue to pursue his goals and principles. A few weeks later I was an usher at his funeral.

I had a final visit with Barry Jr. just before his death in 2006. He was sitting in a recliner in his book-lined library at home, an oxygen tank attached to the side of the chair. Breathing was difficult for him. Barry Jr. loved classical music, and he particularly relished opera and the works of Hector Berlioz. The stereo played softly in the background. The windows were open and the early spring wind caused the curtains to ripple a bit.

Though he usually focused on the future, Barry Jr. was reminiscent that day, reflecting on our lives and on the work we had done together on the editorial page. He suggested it was time for me, at the age of 55, to leave the paper and find something else to do.

On the night of April 3, the 32nd anniversary of the great tornado, I received a call at about 10 p.m. from Barry’s little sister, Eleanor Miller, asking if I would come to sit with her and her sister, Sallie, as Barry was near death. It was a stormy night again, and, in the hours that followed, another tornado would blow through the city — just at the time Barry Jr. died near midnight.

A few days later, several of his friends and I carried his casket into the grand Christ Church Cathedral on Second Street. The Rev. Al Shands ended the eulogy by saying, “Barry kept the flame alive. The flame of this city. The flame of truth. The flame of embracing what is difficult, life-giving, fresh, energizing and inclusive. And maybe what he never quite realized was not only how much he meant to so many, but also that unknown to him he was doing the work of God.”

April 13, 2012, was the day I was to leave the Courier-Journal, after accepting a buyout. Friday the 13th. As I usually did on Fridays, I think I ordered lunch at my desk. Almost certainly a cheeseburger, chips and slaw.

In the end, I was happy to go. I had worked for four decades without a break, in a business where the pressure never really ceases. The thought of months of rejuvenation — reading, walking, perhaps traveling and spending more time with my family — had become far more appealing than worrying about the next day’s editorial pages. Or the ever-present fear of being laid off.

I couldn’t work late that night — although on so many Friday evenings I did — because there was a dinner planned for me at Buck’s. As sunset approached, I put on my raincoat, picked up my briefcase and walked alone down the third-floor corridor I had come to know so well and took the elevator to the first floor. As I exited, I looked at the inscription over the elevator doors. They were the words of Robert Worth Bingham, Barry Sr.’s father who bought the papers in 1918. “I have always regarded the newspapers owned by me as a public trust and have endeavored so to conduct them as to render the greatest public service.”

Share This Article

We want to hear from you. Who or what should more Louisvillians know about? Share here.