The world’s most Louahvul newsletter goes out every Friday. Subscribe at louisville.com/newsletter.

8.27.2021, No. 68

⏱️ = 5½-minute read (or so)

“I doubt it, dude. I doubt it. I strongly doubt it.” — U of L Heisman winner and current Baltimore Ravens QB Lamar Jackson, on if this is the season defenses will finally figure out how to stop him

FIVE.

1. Our new cover, with photography by Sophia Mobley, design by Sarah Flood-Baumann and quote from Anne Shadle of Mayan Cafe.

Thank you, service workers.

2. To give you a sense of how much live music used to sustain me, even just over the second half of 2019: At Forecastle in July I saw Anderson .Paak on Saturday night, then Chvrches on Sunday with Emilia, who was five at the time, on my shoulders; Tim McGraw at Hometown Rising in September; Foo Fighters and Fogerty at Bourbon & Beyond the next weekend; Slipknot, Marilyn Manson and Rob Zombie at Louder Than Life the next weekend; then Tool up in Cincy in November with two of my oldest friends. Haven’t been to a concert since.

But. BUT! Tomorrow, I’m going to Railbird at Keeneland, where Louisville’s own My Morning Jacket, who just announced a new album coming Oct. 22, are headlining. I’ve seen them at Forecastle and Bonnaroo and Headliners and the Palace and the Yum! and Iroquois Amphitheater and, believe it or not, I’m surely forgetting a venue or three. (Btw, is being required to show your vaccination card for the first time like flashing your I.D. on your 21st birthday?)

Gonna go ahead and give MMJ a premature slow clap for making me cry when I hear the first notes to whatever song they open with. (Please open with “Victory Dance,” though.)

👏…👏 …👏👏…👏👏👏…👏 👏👏👏👏👏👏

3. Last week, I mentioned a New Yorker piece, from September 1974, about Louisville titled “City in Transition,” which my friends Stephen George, president of Louisville Public Media, and Keith Runyon, the former editor of the C-J’s editorial page, brought to my attention for its prescience. In 2014, in an opinion piece for WFPL, Runyon said the New Yorker story was published “40 years ago, but it is still relevant today.”

The author, Fred Powledge, found a city “of manageable size” where “its citizens somehow feel it their duty to press upon a stranger…the information that they like Louisville because it is just a good place in which to live, work and play,” and where “change has come slowly.” One guy told him, “Everything comes later in Louisville. If an idea happens on the East Coast, you can look for it in Louisville two years later.” He wrote, “There is also a certain feeling of indolence, a feeling that what you don’t have time to do today can very well be done tomorrow, or even the next day.” (I feel exposed!)

Some enduring observations from the piece:

-“The city is not definitely Northern or Southern, Eastern or Western.”

-“An advertisement…points out ‘many of the nicest things about Louisville are distinctly Southern,’ but it also notes that the city is geographically closer to Windsor, Ontario, than to Memphis Tennessee.”

-“This town, from its beginnings, was kind of a loose town. There was a lot of New Orleans in it. A river town. Pleasuring has always been a part of life here.”

-“Downtown Louisville was pretty much deserted after the evening rush hour.”

-“…a lot of people were close to giving up on the future of downtown Louisville altogether.”

-“There is an old railroad bridge” — ahem, the Big Four — “over the Ohio which the railroad does not use but which…it says it is too impoverished to tear down, and some planners are suggesting that it be made into an interstate boardwalk.”

-Black people in Louisville, like in “most cities, seem to be getting the short end of the stick in terms of the quality of housing, the quality of public transportation, and the quality of employment opportunities available to them.”

-“Alongside apartments and office buildings, they proposed, someone should construct a parking garage.”

-“The document offered ‘a program for revitalizing the Center City area of Louisville.’”

-“In other words, will the plan end up on the shelf? That has probably been the biggest trouble with planning in this city to date.”

Powledge interviewed H. Wendell Cherry, the president and co-founder of Humana, who said, “Somewhere along the line, this city lost pride in itself. And the effort now must be to reestablish pride.” Amid an effort to “restore downtown Louisville’s friendly relationship with the Ohio River,” Cherry (apparently filled with pride?) said, “The river is the only thing of natural beauty here. Of course, it may be polluted, but it’s still pretty.” He went on: “You hear people say, ‘I don’t know whether I want Louisville to be too big.’ They make it sound like it’s a great big place already, but the truth is that the Kentucky Derby is the only damn thing we’ve got in this city, and that lasts two minutes and a fraction, once a year.” Powledge wrote, “Louisville has regained its pride, or a good deal of it, if pride can be measured in glass, steel, and concrete.”

I realize this section is getting lengthy, but I’ve gotta mention two more folks Powledge interviewed:

Democrat Harvey Sloane, new to his job as mayor, had said before the election, “We see the concrete evidence of brick-and-mortar progress all around us, and we have marveled at it and taken new pride from it. But you may have asked what does it do for you. And I think you seek assurance that this city of the seventies will also meet the simple human needs of people living in their own neighborhoods, building a future for their own families.” He said, “People, not buildings. We will not allow the neighborhoods that house and sustain our people to be split, gouged, and torn asunder by purposeless development. Those neighborhoods that have declined, whose houses have been blighted, abandoned or boarded up, must be renewed.”

Jim Segrest owned a brick row house in Butchertown and was a co-founder of Butchertown, Inc., which had purchased three rundown homes in the neighborhood, with a goal of renovating them and turning them into apartments. Powledge wrote, “In the middle and late sixties, Butchertown was discovered by a younger, more affluent group of people, who bought houses and set about renovating them.

“This has happened in a number of American cities, and the result has usually been that well-off suburbanites…buy their way into the neighborhood, driving the sale value of the housing ever upward until all the original, lower-income residents are gone.”

Segrest wanted to prevent that, saying, “We want everybody who’s here here. We have the idea that if there are people in this neighborhood who have problems — social problems, any kind of problems — we don’t want to ‘improve’ Butchertown’s situation by moving them someplace else. That’s an idea that lots of people have, I think: that if you’ve got a problem the best way to handle it is to movie it away.

“The whole idea of the neighborhood will be destroyed if all new people move in and the people who were here move out.”

4. Eden Bridgeman Sklenar, daughter of businessman and former U of L hoops star Junior Bridgeman, is chairing the new parent company that hopes to resuscitate Ebony and Jet, which at their peak were “leading chroniclers of Black life and culture,” according to the New York Times story “Ebony Returns to Chronicle a New Moment.” Sklenar, while growing up in Louisville, “leafed through issues of Ebony and Jet at the beauty salon, where she would go with her mother every week to get her hair styled in tight curls.”

In December, Bridgeman Sports and Media took the brands out of bankruptcy, buying “the assets of their parent company, Ebony Media, for $14 million.” The article includes a sort of mission statement that Ebony’s original publisher, John H. Johnson, wrote for the first issue, in November 1945: The magazine “will try to mirror the happier side of Negro life — the positive, everyday achievements from Harlem to Hollywood. But when we talk about race as the No. 1 problem of America, we’ll talk turkey.”

“We are hoping to uplift,” Sklenar said.

5. Loved this lede (and cover story) from Business First: “Andre Kimo Stone Guess, the new president and CEO of the Fund for the Arts, wanted nothing to do with his hometown for years.”

And also loved this relatable detail, as Guess recalled the uprising in Louisville’s streets in Breonna Taylor’s name: “I started getting a lot of phone calls, a lot of text messages with people asking, ‘Man, what’s going on with your city?’”

Support for Louisville Magazine comes from Ronald McDonald House Charities of Kentuckiana, which is raffling off a flight of five Pappy Van Winkle bourbons. Each of the 1,750 tickets is $100, with all proceeds benefitting families who stay at the House when they travel to Louisville for medical care for their children. Winner announced Oct. 14.

—–

Also, here’s what people are saying about The Power of Giving Away Power, by Louisville Magazine publisher Matthew Barzun:

“Josh, I thought you were going to send me a copy of Matthew’s book?” — a text from my dad.

You should check out Matthew’s website, and order The Power of Giving Away Power from my first love in Louisville, Carmichael’s. Do let me know if you need my dad’s address.

OH!

A little something from the LouMag archive.

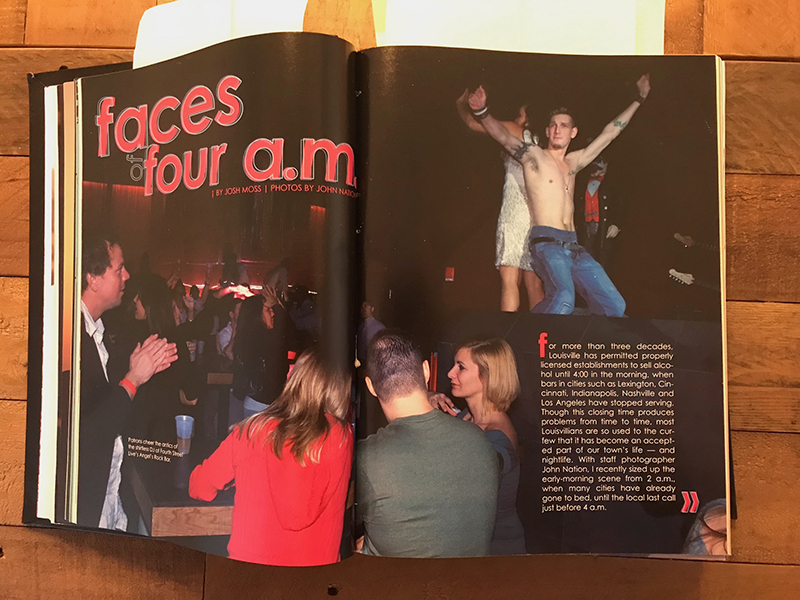

Amid a surge in gun violence, Metro Councilwoman Cassie Chambers Armstrong, whose district includes the Highlands, has filed an ordinance that, depending on a council vote, would prohibit alcohol sales beginning at 2 a.m. instead of 4 a.m., to be in effect until at least the end of the year.

The C-J quoted LMPD chief Erika Shields, who said, “The reality of it is we are so strapped for manpower that the added two hours may not sound like much, but it is when you have multiple incidents arise.” (WAVE-3 cited LMPD’s “250-officer shortage” as “an underlying source of the issues plaguing not just the Highlands, but the entire city.”)

In the C-J, Councilman Bill Hollander, whose district includes Frankfort Avenue, said, “I hope Council members will recognize that many people, including people in our hospitality industries and others, don’t work traditional day shifts and would be significantly impacted by this. We should keep those people — and businesses where there have been few or no problems — in mind.”

In early 2008, my editor asked me to spend a month’s worth of weekends at bars until 4 a.m. for a story. (“Because I’m 22 and will already be doing that?” I prolly replied.) Back then, the city categorized 225 establishments as a tavern, bar or nightclub, and 183 of them, or 81 percent, could serve until 4 a.m. (According to a recent WFPL story: “Of the 171 Louisville bars and restaurants able to serve alcohol until 4 a.m., most are concentrated in downtown and the Highlands.”)

In ’08, I wrote: “A Derby-inspired 1974 ordinance nudged the city down a track toward a yearlong 4 a.m. curfew. That ordinance established that alcoholic beverages could be sold ‘any time between 2 o’clock a.m. on the first Saturday in May of each year through 6 o’clock a.m. on the following Sunday.’ On Jan. 14, 1975, the Board of Alderman passed another ordinance on alcohol sales. Among its provisions: legal year-round sale of alcohol from 2 a.m. to 4 a.m. In a letter addressing the issue, then-Mayor Harvey Sloane” — yep, the same guy I mentioned above in No. 3 — “acknowledged concerns that such a law could ‘signal an atmosphere of permissiveness, increasing problems of uncontrolled drinking and contributing to traffic accidents and crime.’ But this wasn’t enough to prevent him from allowing the ordinance to become law, though he refused to sign, indicating his reservations. He wrote, ‘Police officers who have worked during previous Derby weekends said the longer hour did not appear to exacerbate the problems of law enforcement,’ adding that he was aware of the ‘benefits that longer drinking hours might provide in our efforts to attract the convention business that is so beneficial to Louisville’s economy.’”

Back then, I called Sloane, who was living in Washington, D.C., and he told me, “I don’t really remember it being a big issue. I don’t recall that we got any adverse reports from the police or the public on it.” A member of the band John Baxter and the Bottomfeeders, which played at Molly Malone’s on Baxter Avenue, told me one thing he found to be true: “People are definitely drunker as the night wears on. They pretty much eat up anything you play.”

TOO…

Emilia, my second-grader: “Dada, we need to keep brushing our teeth so they’re extra, extra sparkly when we finally get to take off our masks.” Take that, stereotypes about oral hygiene in Kentucky!

Josh Moss

editor, Louisville Magazine

josh@louisville.com

Read past newsletters here.