Who or what should be on a future cover of Louisville Magazine? I’d love to know what you think

— Josh Moss, editor, josh@louisville.com

Who or what should be on a future cover of Louisville Magazine? I’d love to know what you think

— Josh Moss, editor, josh@louisville.com

.

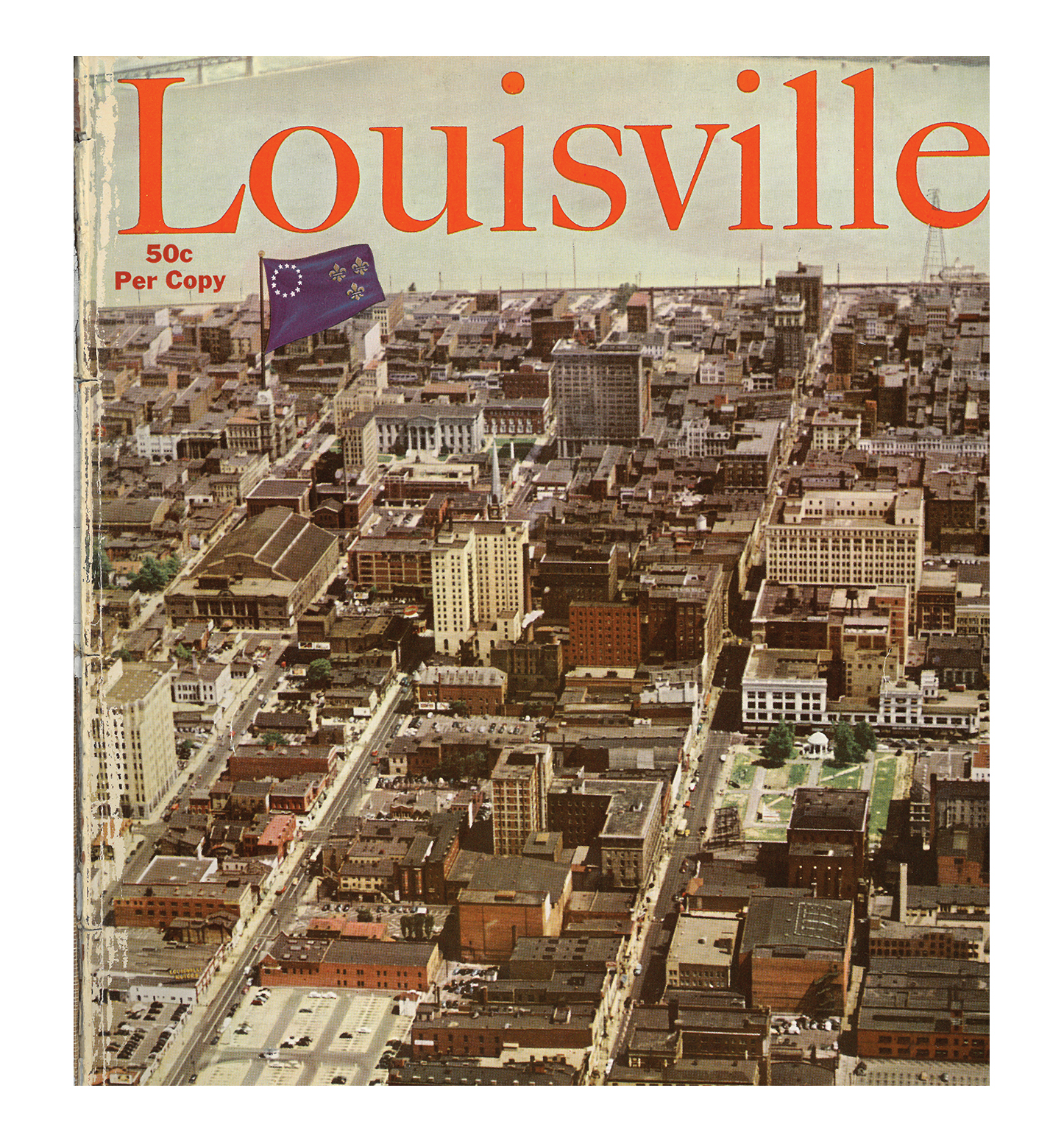

“As someone studying in New York, the City of Dreams, I think of home and, really, every city as a city of dreams — and dreamers. Looking at this cover, I wonder: What did they dream Louisville could be in 1950? I wonder if their dreams came true — and then — will ours? The author of The Little Prince says that a dream without a plan is just a wish. Religion, whether we practice one or not, says that there’s no faith without work. So, here we have: to feel the need, to plan for it, to work to make it happen. I know the most impacted of systemic issues have worked for generations and will work for more generations. I also see the same dynamics that have prevailed throughout history: those without power demanding, appealing to those with power, to give them their due. I wish for this, but I do not plan on it on its own. I don’t believe my voice to be that much more compelling than my ancestors’. To make Louisville the city we wish it to be, I believe that planning has to include a complete shift in dynamics and imagined possibilities. When we plan, do we see the other side? Do we think on how to maintain it? Is it generative or is it a goal that, when we capture it, we’ll look at each other asking: What’s next?

“A wish can be a dangerous thing when left unattended. It has to be held properly or it festers and twists into something…other. So my big question is: Who are we counting on to tend to our wishes? That’s the question I hear behind, ‘What will Louisville look like in another 70 years?’

“The beautiful thing is, we can all wish, we can all plan, we can all work. That already matters. When we do it together, there’s no established power more powerful.

“Show them. Make Louisville.”

.

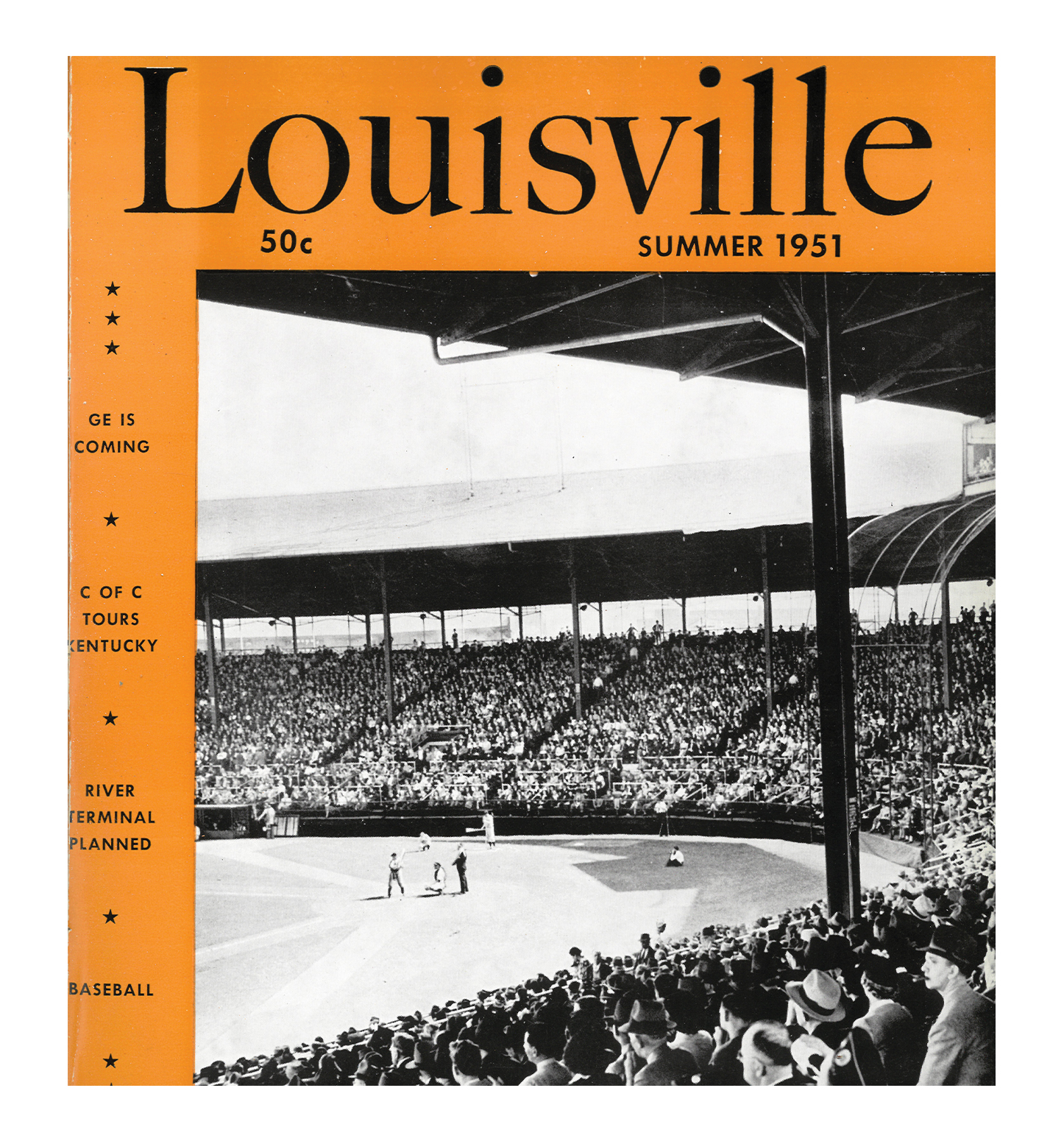

“I was a wide-eyed boy arriving at Parkway Field, home of the Louisville Colonels, to see his first professional ball game with a troupe of Little Leaguers from Corydon, Indiana. The parking lot was full of black Fords and Chevys, and the ballpark was an Erector Set of black-painted iron beams and gray concrete ramps. But up in the stands, that drab world opened onto an emerald-green diamond of carefully clipped grass, stretching away to red brick outfield walls, set below the then-modern Eastern Parkway overpass. A parkway field.

“The outfield wall angled 90 degrees to deepest center field, an astonishingly distant 485 feet from home plate — deeper even (by two feet) than the New York’s Polo Grounds. We learned that the only hitter ever to whack a home run over the Louisville center field wall was Babe Ruth, in an exhibition game. We also learned that Hall of Fame shortstop Pee Wee Reese began his pro career at Parkway Field, signed by the AA Colonels out of duPont Manual High.”

.

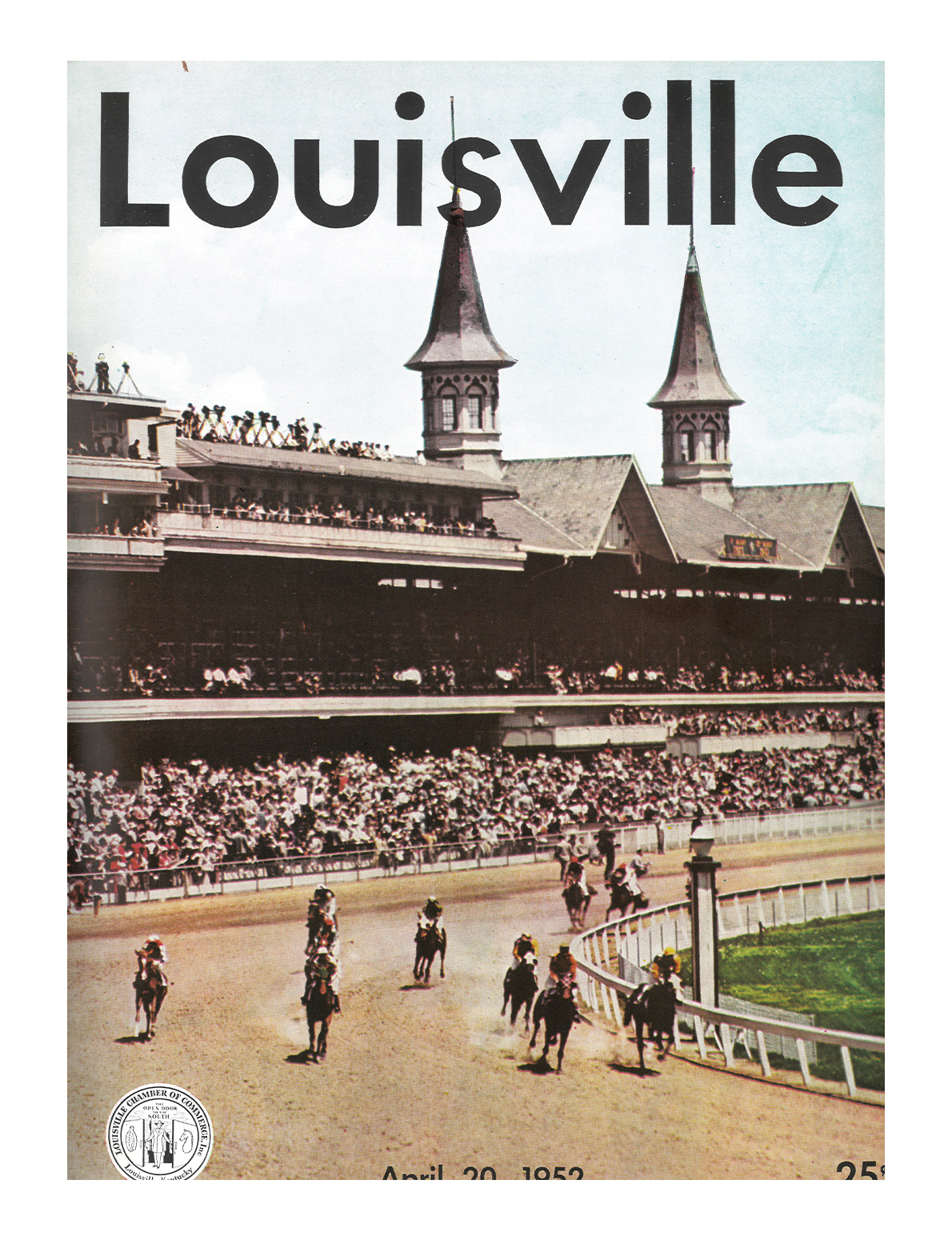

“When I look at this cover from 1952, I can hear the cacophony of voices since 2003’s renovation that constantly say, ‘Churchill Downs needs to raise up the Twin Spires!’ As a lifelong Louisvillian and Thoroughbred photographer, this sentiment has been expressed to me thousands of times. While I certainly understand this impossible architectural wish, we should all treasure the historic preservation efforts that have kept our city’s most famous landmark intact for 150 years despite a constant evolution of the grounds. This cover definitely captures the historic majesty that we all miss of the Twin Spires towering over the track, but if we didn’t evolve, I would still be carrying around a behemoth wooden tripod like those photographers on the roof.”

.

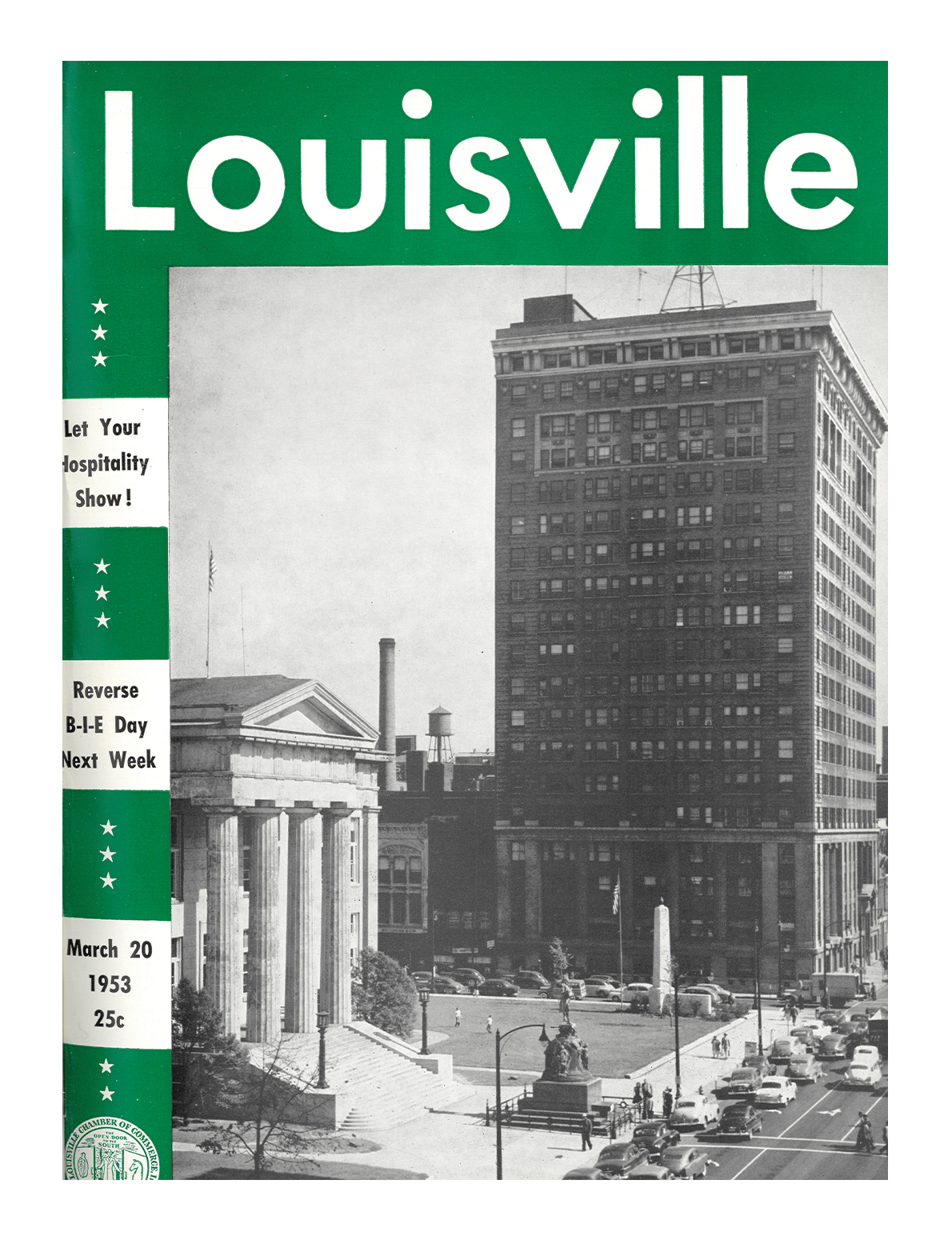

“When I saw this picture — the cars, people walking downtown — I was immediately reminded of a Life Behind a Veil quote by (the late Louisville native and University of North Carolina) professor Blyden Jackson. He states, ‘Through a veil, I could perceive the forbidden city, the Louisville where white folks lived. It was the Louisville of the downtown hotels, the lower floors of the big movie houses, the high schools I read about in the daily newspapers, the restricted haunts I sometimes passed, like white restaurants and country clubs, the other side of windows in the banks, and of course the inner sanctums of offices where I could go only as a client or a menial custodian. On my side of the veil, everything was Black: the homes, the people, the churches, the schools, the Negro park with the Negro park police…I knew that there were two Louisvilles and…two Americas. I knew also which America was mine.’

“This magazine cover was made in 1953. It was not until 1963 that Louisville passed an open-accommodations ordinance fueled by a Nothing New for Easter campaign. This was a boycott of clothing stores by Black people that intended to apply economic pressure on store owners during the ordinarily busy Easter season. The protests were focused on the Fourth Street shopping district, where Black people were often discriminated against and harassed when attempting to make purchases or eat at certain restaurants.

“I am being asked to write about an image of a time in Louisville that I could have never experienced. That my father, who was born, raised, and died in Louisville, couldn’t participate in.

“In 2020, I stood outside this very same building (the Jefferson County Courthouse) and was teargassed in my old Kentucky home while protesting the death of Breonna Taylor. This photo is simply a reminder that Louisville will always remind Black people that we live in two Louisvilles and rarely, if ever, are Black people allowed to experience life beyond the veil.”

.

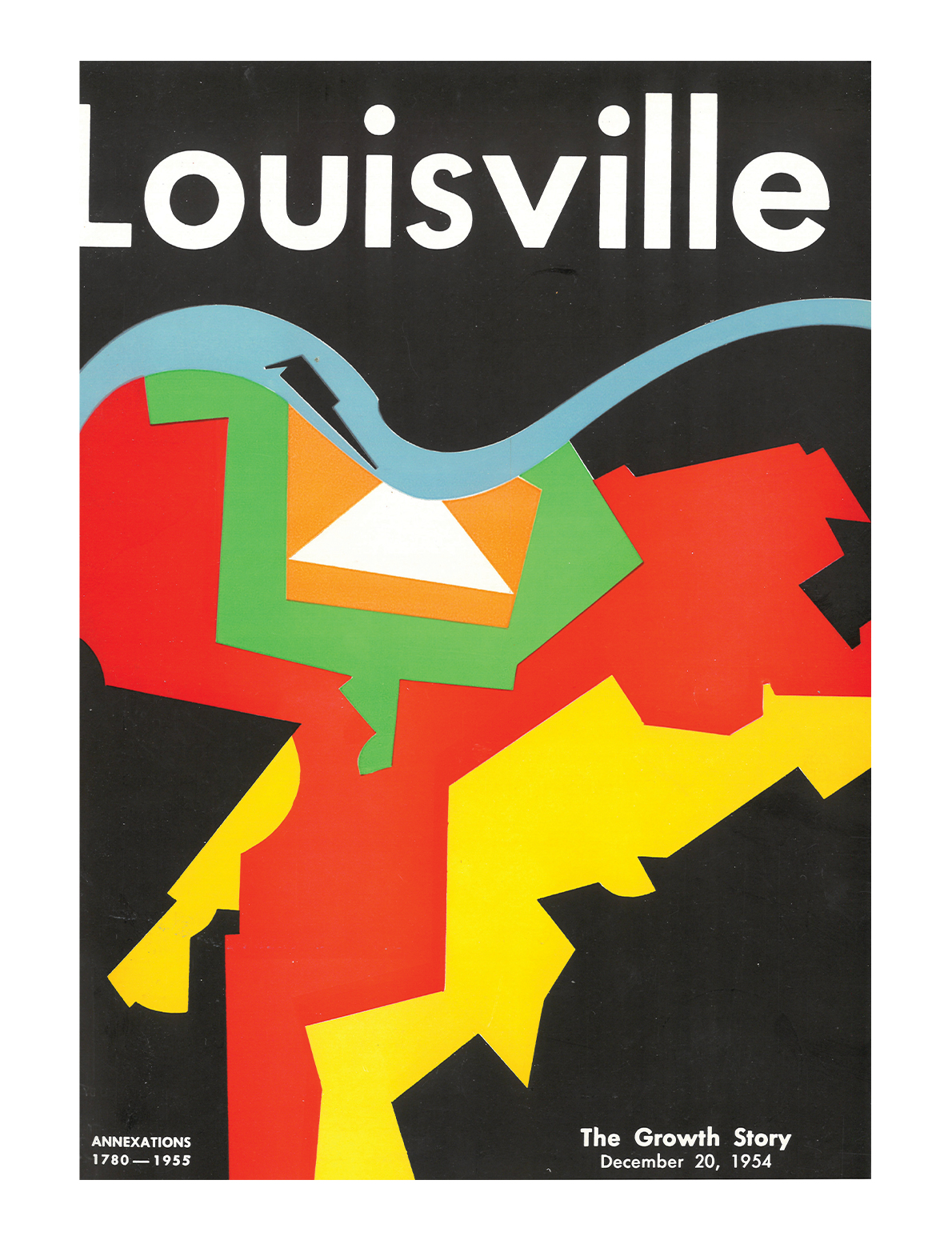

“This 1954 map shows the impact of 20 years of redlining, and starts to show the impact of folks with resources leaving west Louisville after the Great Floods of ’37 and ’45 (the second-biggest flood ever). I-64 was built in ’56, construction on our flood wall commenced in ’57 (both displacing many Portlanders), and then I-65 was built in ’58, right about when urban renewal (what James Baldwin famously called ‘Negro removal’) started, cementing (literally) the division of Louisville into east and west, finished off by the construction of the multilane freeway of Ninth Street in the ’60s. While the population of the city of Louisville shown in this map has barely increased, the greater MSA (metropolitan statistical area) has increased, but only gradually, over the last 70 years. To make any claims about Louisville being a growing, vibrant city, a modern iteration would have to include southern Indiana and the surrounding counties.”

.

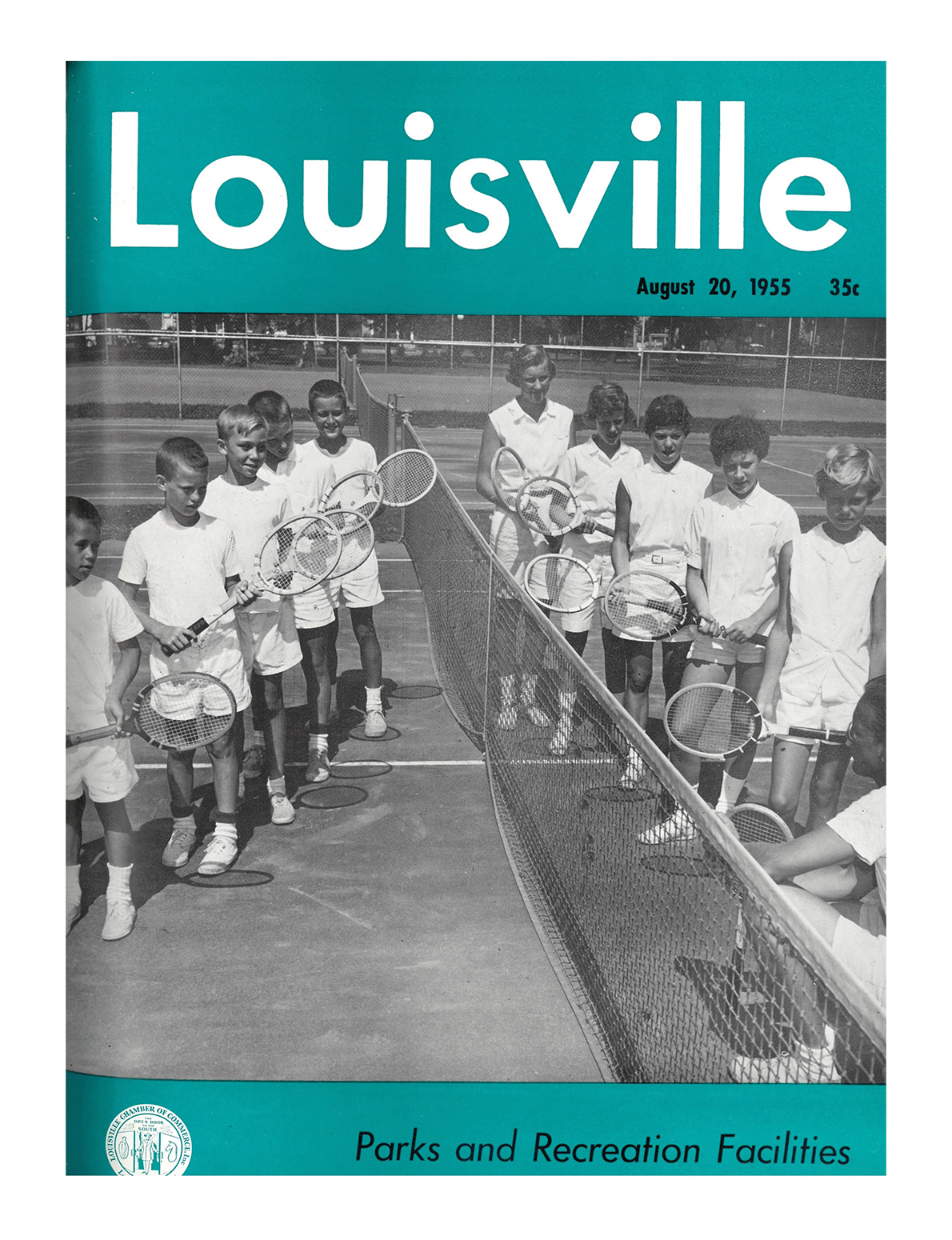

“My initial impression is: Thank God for grace, mercy, diversity and inclusion! For African-Americans, there was a time when participation in cost-prohibitive sports such as tennis was limited, as you can see from your 1955 cover. Historically, in the game of tennis, there have always been exceptional ‘players of color’ to include — people like Arthur Ashe, Althea Gibson, Zina Garrison, Chanda Rubin and Venus and Serena Williams, just to name a few. As a result of the diversity and inclusion initiatives undertaken by the United States Tennis Association (USTA) and many other noteworthy local organizations, such as Olmsted Parks Conservancy, Louisville Parks & Recreation and USTAKY, tennis has become a viable recreation alternative for underserved communities, too. I played basketball in my high school and collegiate career, but I never viewed tennis as a viable option. It’s a shame, too. My earliest memory of playing is around 1984. It was in Louisville, right in Chickasaw Park.”

.

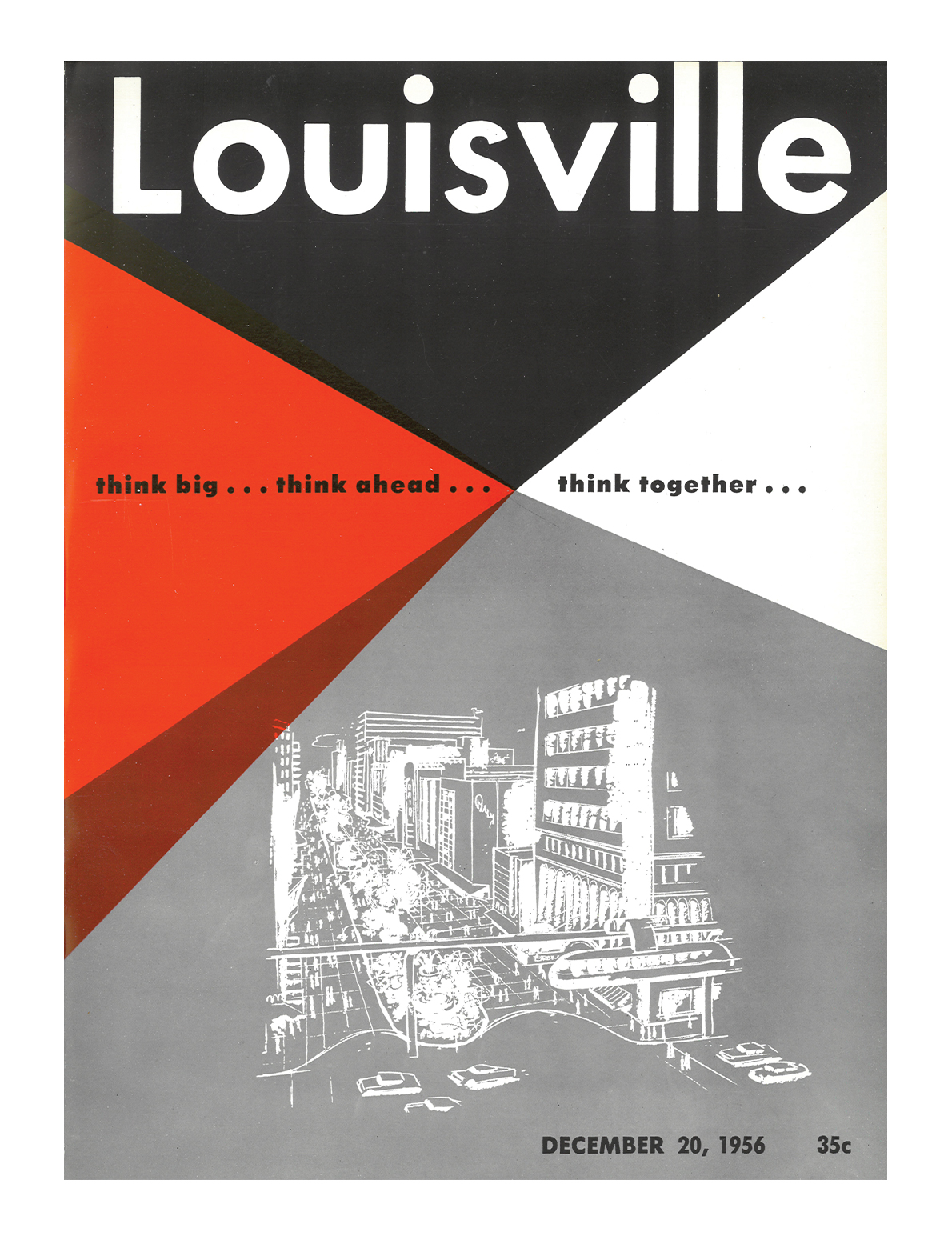

“It’s truly bittersweet. In 1956 the dreamers and believers imagined a walkable urban core full of green space, healthy air and electronic transit. I hope that they dreamed of racial and economic equity, access to healthcare and reparations as well.

“Truthfully, we’re not quite there. So often in life you hear the phrase ‘If you build it, they will come.’ Louisville has a different challenge, in that the only reason many of us will stay is if the gatekeepers move to the side and let us build the Louisville we know people deserve — bridging disparities and increasing true equity along the way.”

.

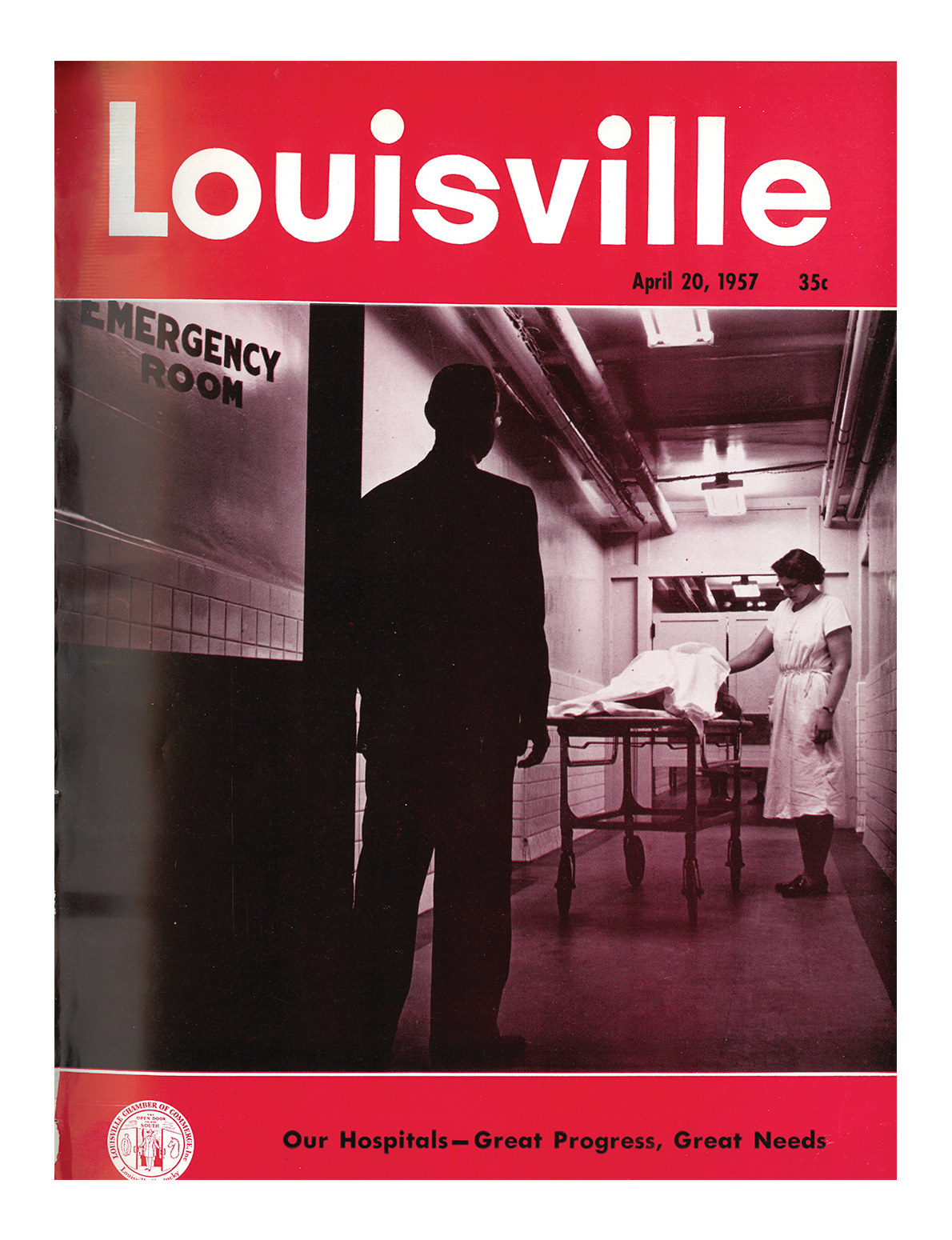

“It’s striking. The first thing I see looking at this picture, sadly, is that these healthcare workers aren’t wearing masks, and what must that be like.”

.

The cover caption (apologies!): “Girls seldom grace the cover — or even the inside pages — of this businessman’s magazine….” (The Louisville Area Chamber of Commerce owned Louisville Magazine until the early ’90s.)

“Reading this caption from 1958 is astounding because Louisville has so many vibrant women in business now. However, a lot of typically male-dominated industries are STILL dominated by men — and mostly white men. As a woman who owns a bar — without any male investment, I might add — I am among the minority of bar and restaurant owners in Louisville. Though we have a lot of retail shops, gift shops, coffee shops and bakeries owned by women, there are far fewer in the bar and restaurant categories. It is also pretty normal for me to flip through a local publication boasting the top 10 chefs of Kentucky or the top 10 beverage directors of Kentucky see that and most of them, shock me shock me, are white men.

“I’d like to see things shift a lot in the next 10 years. Not just more female business owners but more women of color or trans women in places of power. People who don’t have the easy path often are better equipped, tougher and more creative about how to run a business. I want Kentucky to lead the way and pave the path instead of being 10 years behind everyone else. I believe it starts with your story, and your business practices, and putting those values first. I value women and trans women in business, and I am here to solidly support them in every way possible.”

.

“What strikes me about this cover is that although there are, as this issue preordained, a fairly significant number of residential places to rent or buy in the central area of Louisville, we still face many ‘challenges in housing.’ Chief among these is a lack of quality affordable housing. The city and private developers have done an admirable job of creating downtown inventory for young professionals and upper-middle-class folks who want a more urban living experience and can spend $2,000 a month on rent or $400,000 to buy a condo. What we’re missing are well-designed, well-built units that working artists, musicians and service workers can afford, as well as rent-controlled housing that facilitates a much broader and more racially and economically diverse population. Without this mix of housing options, I’m afraid our city center will end up homogeneous and uninspired, but I’ve still got hope we can figure it out and, in so doing, reach our considerable potential.”

.

“And it has only gotten worse. Sixty years later and the cost of healthcare just continues to skyrocket. No progress. It’s sad.”

.

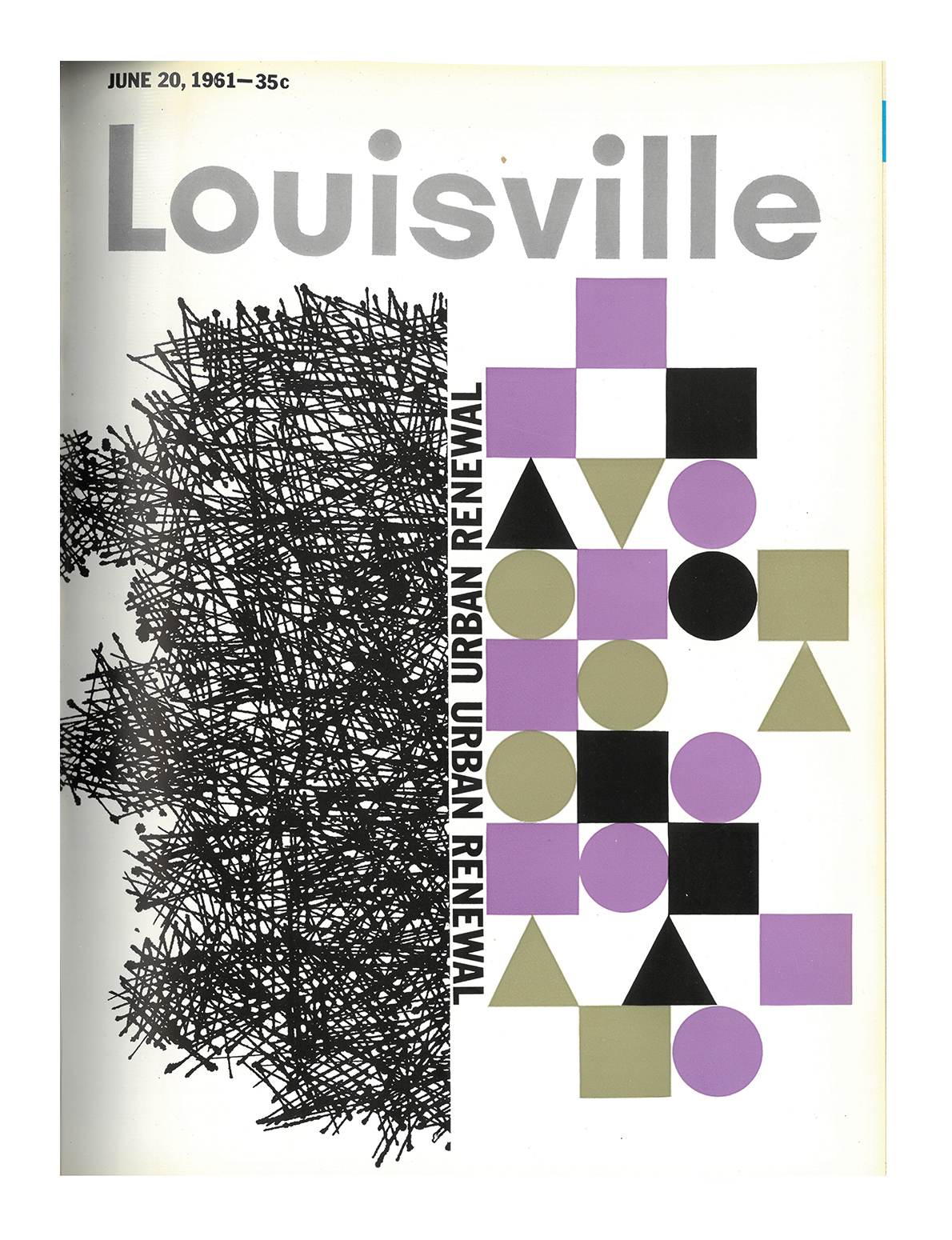

“In retrospect, we know urban renewal was urban destruction and Negro removal. This is what created the Ninth Street Divide: Black social isolation, economic disinvestment and white flight!

“I remember vividly the riots of 1968. My father’s real estate company was on 28th and Greenwood. The saddest thing for me is all the brilliant people who were born, lived and died under extreme racial oppression and never had the chance to see their talents maximized and developed.”

.

The cover caption: “…a representation of Louisville’s bustling restaurant business. Sorry, we didn’t have time to count the number of customers.”

“Louisville had a bustling restaurant scene in 1962? As transplants — we’ve been here since 1987, but still — we’ve always heard that there wasn’t much of a scene until the Bristol brought bistro-style dining to town and started the independent boom in the late 1970s. What does look very 1962 on the cover is the tableside service, the white tablecloths and what appears to be a completely white clientele. It’s nothing like the Irish Rover, and yet a happy, crowded, busy dining room is absolutely the vibe of the pre-Covid Rover (the lack of Black and brown faces notwithstanding). Will we ever be a restaurant with this sort of nonchalant exuberance again — sitting close, enjoying the pleasure of company without masks, table-hopping to visit friends and family? And after a year of unpleasant experiences as the mask police, will service professionals ever regain the joys of a great team offering great hospitality? We sure hope so, because this is the essence of an Irish pub. Good food and drink are a starting point, but without a heartfelt welcome, without music, without joyous laughter, without stories told loudly, it all falls flat.

“The actual shutdown order came March 16, 2020, the day before St. Patrick’s Day, but, by then, it was no surprise. We had already canceled our annual tent party, but we still had a refrigerated truck sitting beside the building filled with the makings of hundreds of orders of fish and chips, Guinness beef stew, and leek and potato soup. We also had two more trucks filled with beer. Huge financial outlays, now with no way to recoup that money. We didn’t know what the future held, and we knew NOTHING about the virus. When we came together the next day — a very weird St. Patrick’s Day — and for the rest of the week, we worked to sell those vast amounts of food on a carryout basis. As an indicator of how little we knew, we were cleaning surfaces like crazy people but also working closely together without masks. We worked in a state of shock that first week, then gave away the remaining food and shut temporarily to assess the financial situation, learn about the virus and try to figure out a path forward with PPP money and a new online-ordering system. Since then, every day is a new experience as we continually adjust to keep staff and guests safe while keeping the business going. We are grateful for the government programs that allowed us to put safety first while continuing to pay our staff, and especially grateful to the staff who trusted us to keep them safe and joined us in the hard work of offering carryout and outdoor service only. We hope to move inside ahead of the cicada infestation, and we hope that a robust vaccination program will bring us back to the sorts of joyful, crowded, celebratory gatherings pictured (but with a lot more Black and brown folks in the picture).”

“The pandemic has changed a lot of things about the restaurant industry, but one thing Louisville has stayed true to is its love of seafood. We’ve been lucky enough to say business has grown — new customers and those who have been faithful from the very start.”

“This cover reminds me of the coziness that Mayan had prior to Covid. We had 14 tables in our small dining room, and they were packed almost daily. It’s hard to imagine a world where we are so intimately bustled together and so carefree again. But here’s hoping.”

.

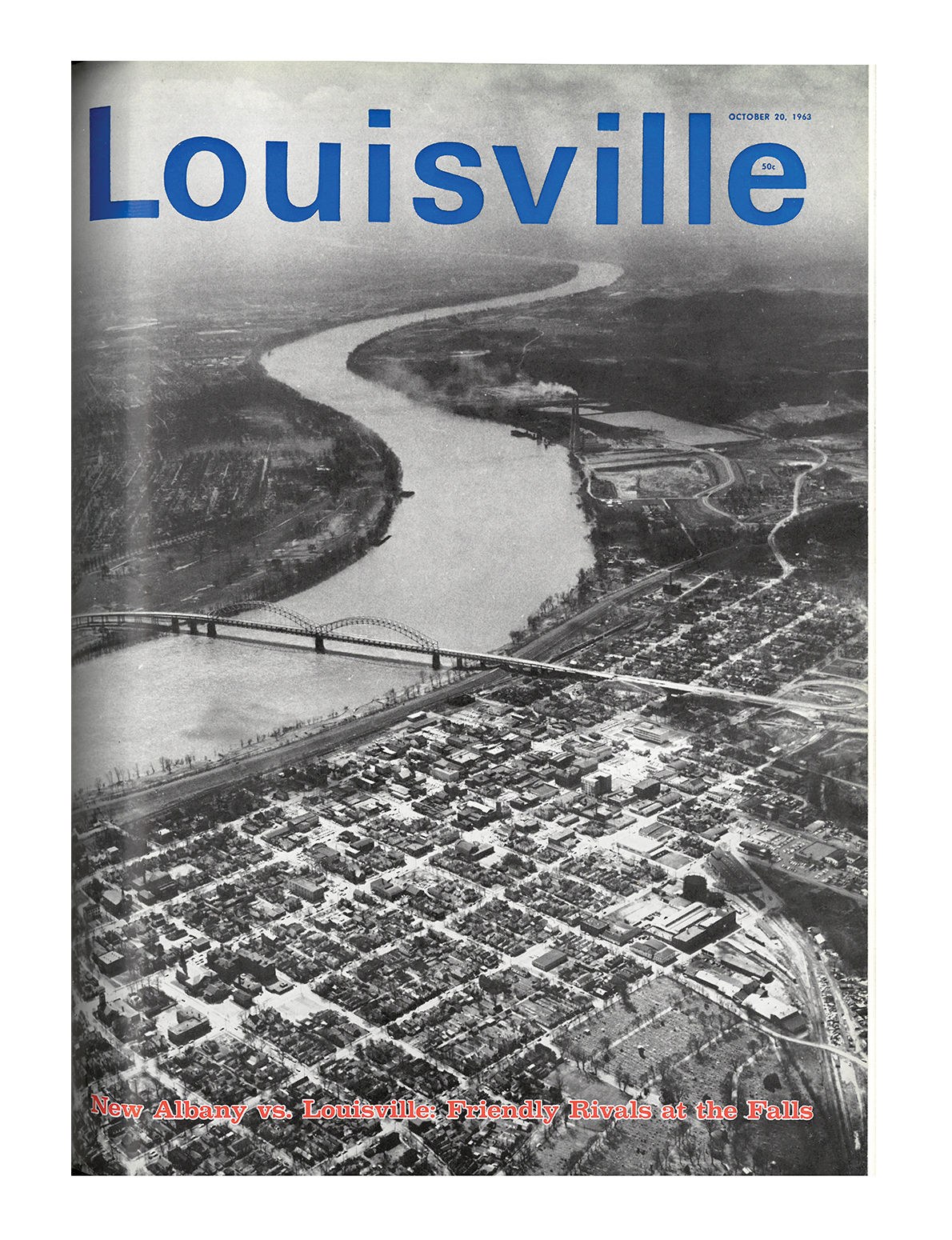

“After moving from Michigan to Louisville in 2002, I rarely gave Indiana much thought. It seemed like a whole other world — not a rival — and my career mostly kept me working in Kentucky. The Ohio River seemed to serve as a barrier instead of a connector like I view it today. Even the use of the term Kentuckiana put Kentucky first and Indiana as an addendum, an afterthought. But I started to ask why once I fostered relationships with Hoosiers. I am now a proud Southern Indiana resident who sees how imperative collaboration between the two regions is. Working together is necessary and beneficial. So is retaining the uniqueness each offers.”

.

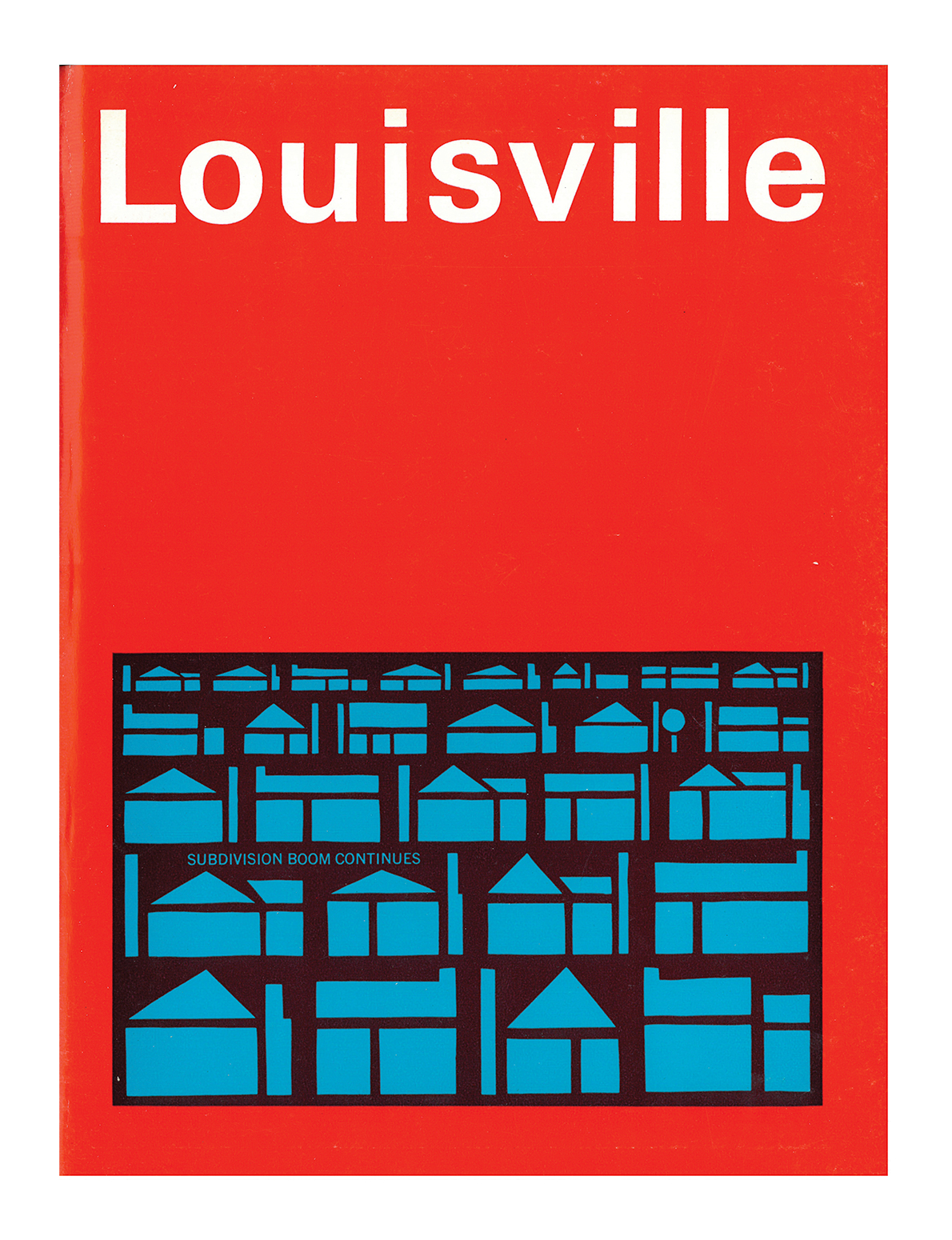

“This magazine cover has a design aesthetic that is definitely of its time. I’m reminded of the iconic movie posters produced in the 1960s by graphic designer Saul Bass. The use of simple color-block shapes is quite clever in how it interprets the repetitive vocabulary of suburban structures. The recombination of this kit-of-parts attempts to create variety but ironically emphasizes that they are essentially identical. The fact that these shapes are gathered into a rectangular box also underlines a sense of isolation and a ‘blank slate.’ It’s a perfectly mown lawn. I wonder if the cover is a satirical graphic commentary on suburban architecture.”

.

“Schools never closed during Covid. Only the buildings did.”

.

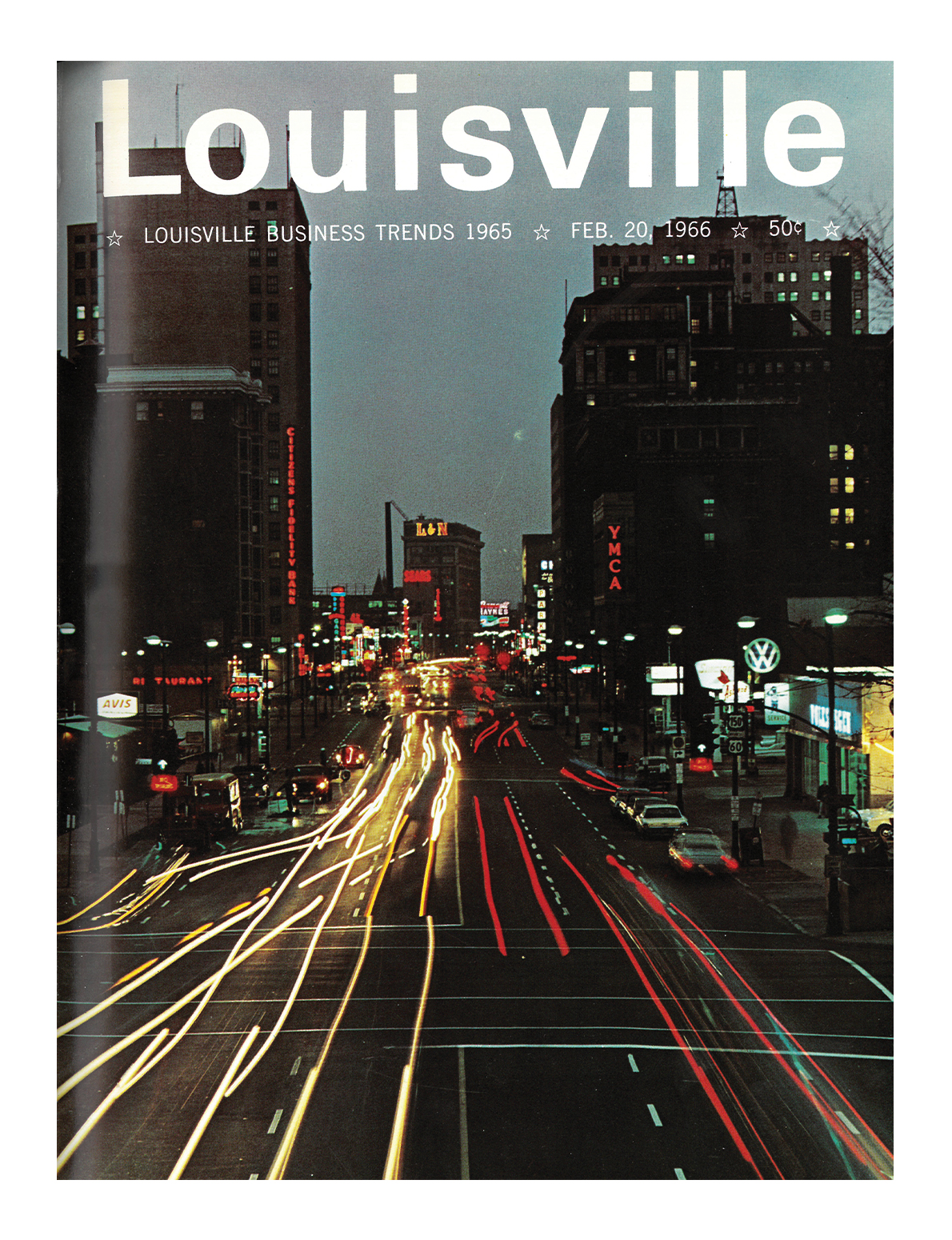

“Wow, some big changes in the 55 years since this cover photo was published. The big, bright neon lights that used to fascinate me as a kid no longer brighten up the evening in the westward drive down Broadway. The L&N sign and its ever-changing light show always captivated my attention. The YMCA where I learned to swim in the basement pool has relocated to Second and Chestnut streets, and the magnificent St. Francis School now carries on the tradition of youth development in that piece of real estate. Along with the businesses themselves, long gone are the huge signs on the Heyburn Building for Fawcett-Haynes printing, Sears and Citizens Fidelity Bank. Who would have predicted that those three leading businesses would no longer be in existence in Louisville today?”

.

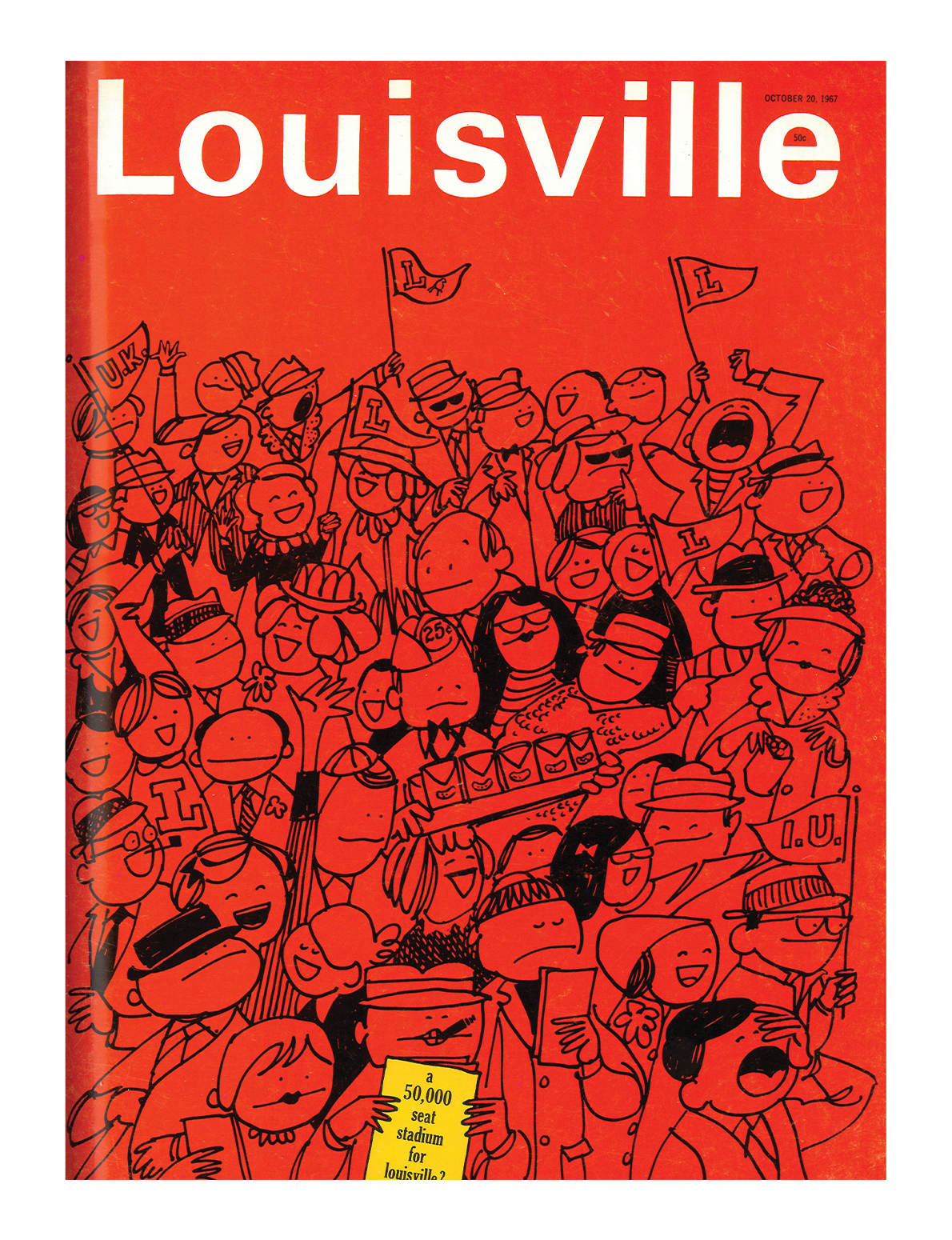

“I got here in 1986, and there was talk of building a new multipurpose stadium downtown. Howard Schnellenberger was rebuilding the football program, and Denny Crum was just coming off a national championship. WLKY did a series in 1988 — ‘Is It a Dome Idea?’ — about the possibility. All this talk, started in 1967, eventually led to Cardinal Stadium and the KFC Yum! Center.

“This cover foreshadowed an unprecedented growth in facilities driven by former athletic director Tom Jurich, fueling historic success in a variety of sports and likely will continue to when this Covid storm passes. And it will pass. It’s fascinating looking at this cover over a half-century later, living in a coronavirus world where crowds are at a minimum and socially distanced. During the pandemic, the first UK basketball game I covered, hosting Notre Dame, felt like an episode of the Twilight Zone. Just echoes off the empty seats instead of the normal pomp and circumstance. I kept waiting for Rod Serling to come around the corner.”

.

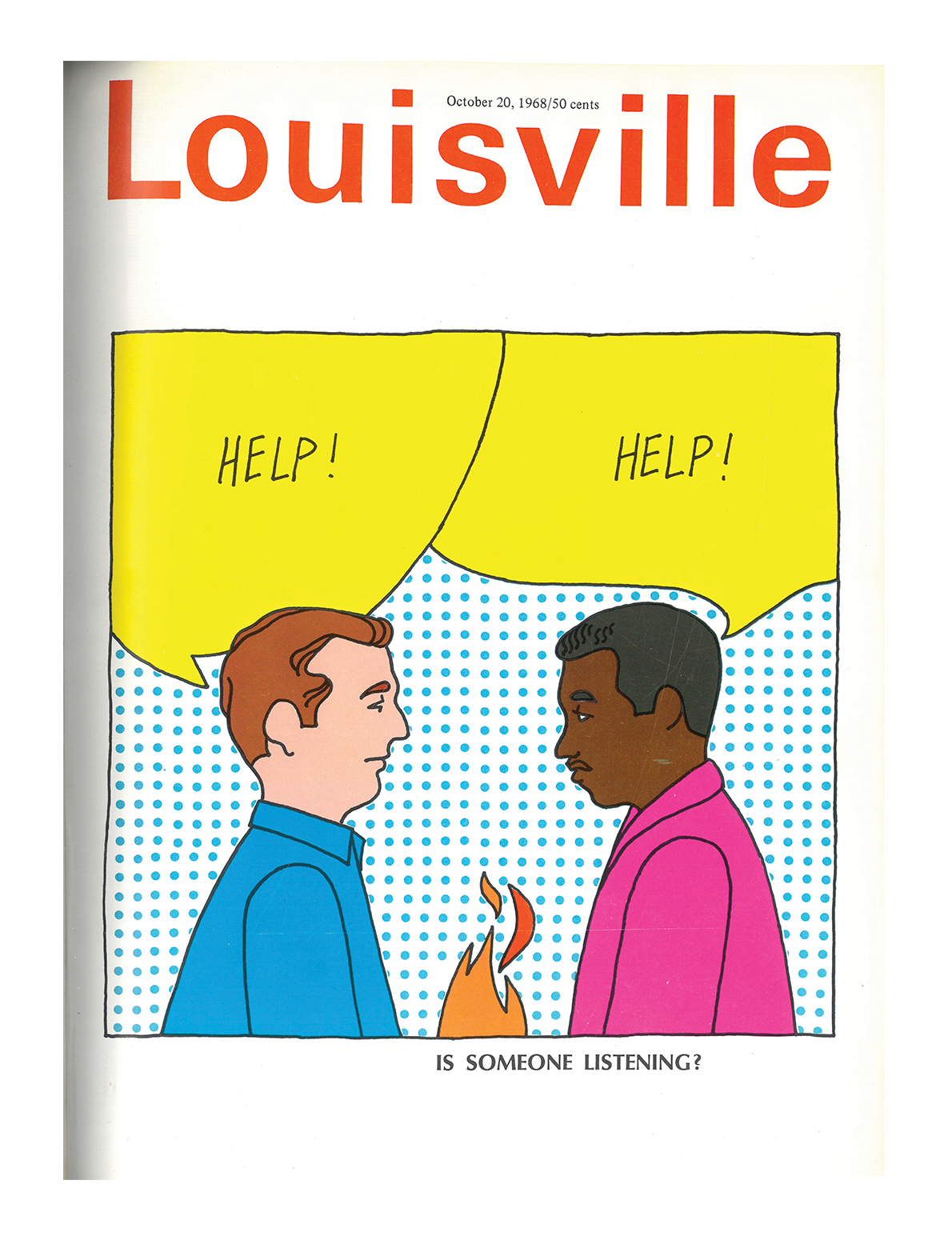

“When the homies are open about their mental states with each other and have a fire handshake 🤝🔥”

And from Louisville Urban League president and CEO Sadiqa Reynolds (who later in this package also shares her thoughts about a cover from 1988): “And the fire still burns because no one was listening. Can you hear me now?”

.

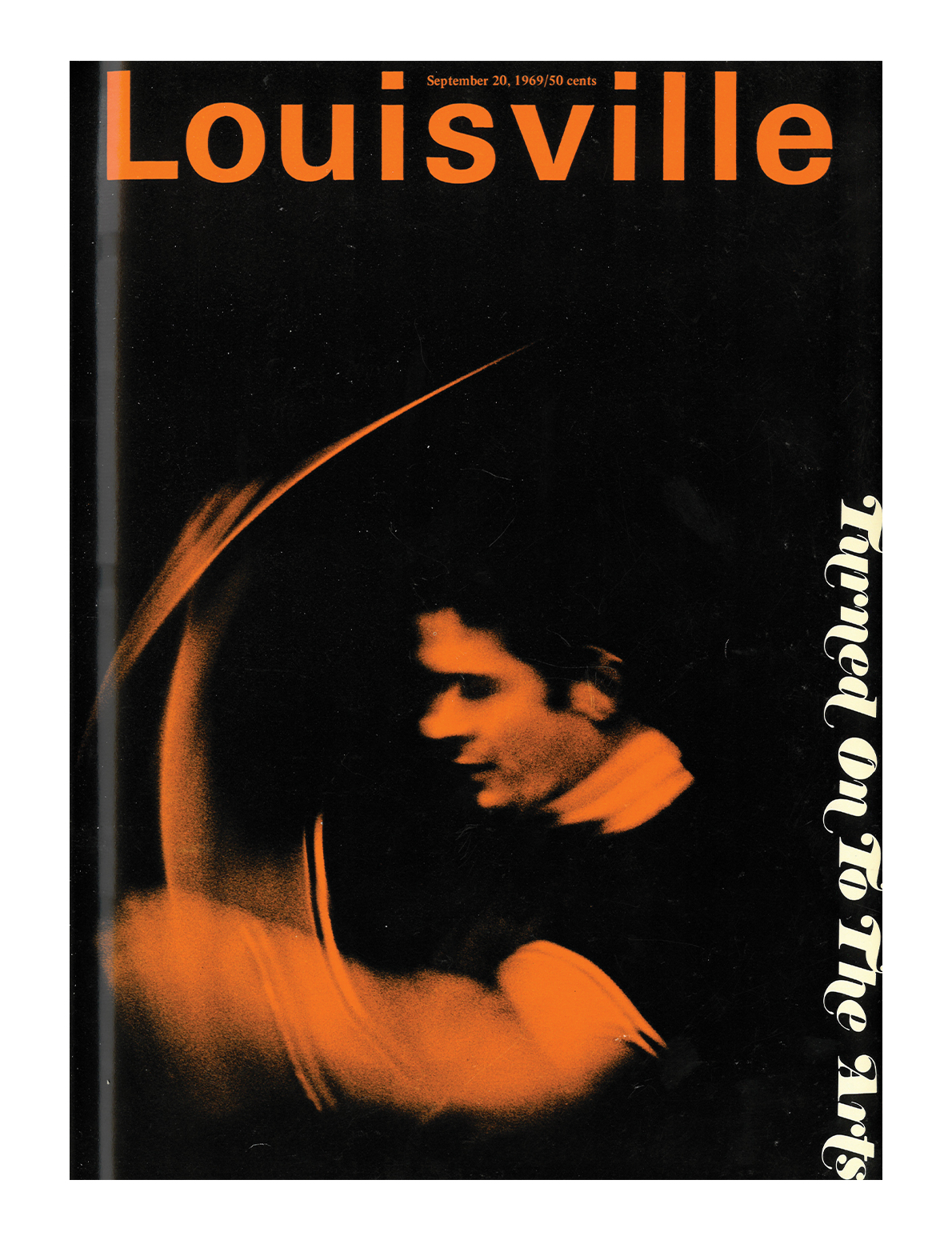

“The arts are the prism through which many people view their world. Artists always filter their creativity through the environment in which they exist. Louisville, as a city, has always had a strong connection to the arts and has always been a community that has strongly supported the arts. This cover (pictured: former Louisville Orchestra director Jorge Mester) demonstrates the leading role that the arts played in the community. The Louisville Orchestra has always been an important part of the artistic tapestry of the city. From their First Edition series of recordings of new works to the diverse programming of current musical director Teddy Abrams, the Louisville Orchestra has been at the forefront of new artistic directions. Yet, one cannot help but think of this cover in the context of what was going on in the world in the late 1960s. It was a time of uncertainty and conflict. To me, the unfocused nature of the cover reflects that uncertainty much as the uncertainty of today is reflected in the artistic work of many musicians. As was the case then as it is now, the world turns to the arts to guide us through the challenges of our world. The arts always speak to the essence of the times. Without the arts, where would we be and how would we understand ourselves and our world?”

.

Cover caption: “The sweet-acrid aroma of marijuana is beginning to permeate the premises of business and industry along with the more critical menace of hallucinogenic drugs and hard narcotics.”

“This made me think of how well we can identify a problem, write about it, talk about it and even sing about it for 50 years without solving it. I often think about the folk singers who wrote about discrimination, the environment and freedom in the ’60s, and how sadly relevant their words are even today. ‘And the answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind.’”

.

“While the intent was likely executed in good spirit, there is evidence that a Black voice was likely not at the table for the decision to review the cover photo before publication.

“Black businesses were present in Louisville during the 1970s, and not having a face to go with the title was an egregious miss. Black businesses deserve that visibility, then and now. The other major miss was not bringing in Black business leaders who could provide that ‘know-how’ to other businesses. There were discriminatory practices, policies and underlying issues that hindered Black businesses. Yet many grew, and their priceless knowledge deserves a platform so it can be passed along to the next generation of Black business owners.

“Recognizing that these challenges still exist today, I am glad to see so many forms of incubators and programs designed solely to help build, grow and sustain Black businesses. This was a need in 1971 and still is today.”

.

“Hope now wanes on the low-cost housing scene. We are desperately trying to help neighbors avoid evictions, not only because it is financially and mentally devastating, but also because there is nowhere for them to move. Extended-stay hotels are full of families who are paying $1,200 a month because they have lost too much money on applications for new housing. They do not make three times the rent and have a bad credit or rental history, so they are denied again and again. There is nowhere for them to go, and spending every last dollar on a hotel for three years until their name makes it to the top of the Section 8 waiting list is not a solution. We need to pass new zoning policies that allow for multi-unit development. We need to fund community-led development to keep investment local. We need to ensure rent assistance to prevent evictions after Covid relief dollars disappear. We need more housing voucher programs. Then, maybe, hope can reign again.”

.

“I think it is pretty interesting that the main topic of ecology and economic development was being discussed, an issue that could be as important today as 47 years ago, if not more so. Part of me doesn’t want to read the article, though, because I would feel pretty deflated if they discuss the very issues we are dealing with today that have not been addressed. It is why I consider myself more of an urban designer than an urban planner. I think plans have their place, but most of them end up on shelves in my experience. That’s why I’ve focused more of my efforts on tactical urbanism, placemaking and activations, which prototype and test ideas in the city’s built and natural environment. We don’t have the luxury of waiting for big projects to materialize to fill in the gaps in our urban fabric to make Louisville work for everyone, and we can’t put off fixing the ecological issues facing us, because the existential problem is a few decades away, not generations. We are the ones who need to do the heavy lifting, and that requires doing something now.”

.

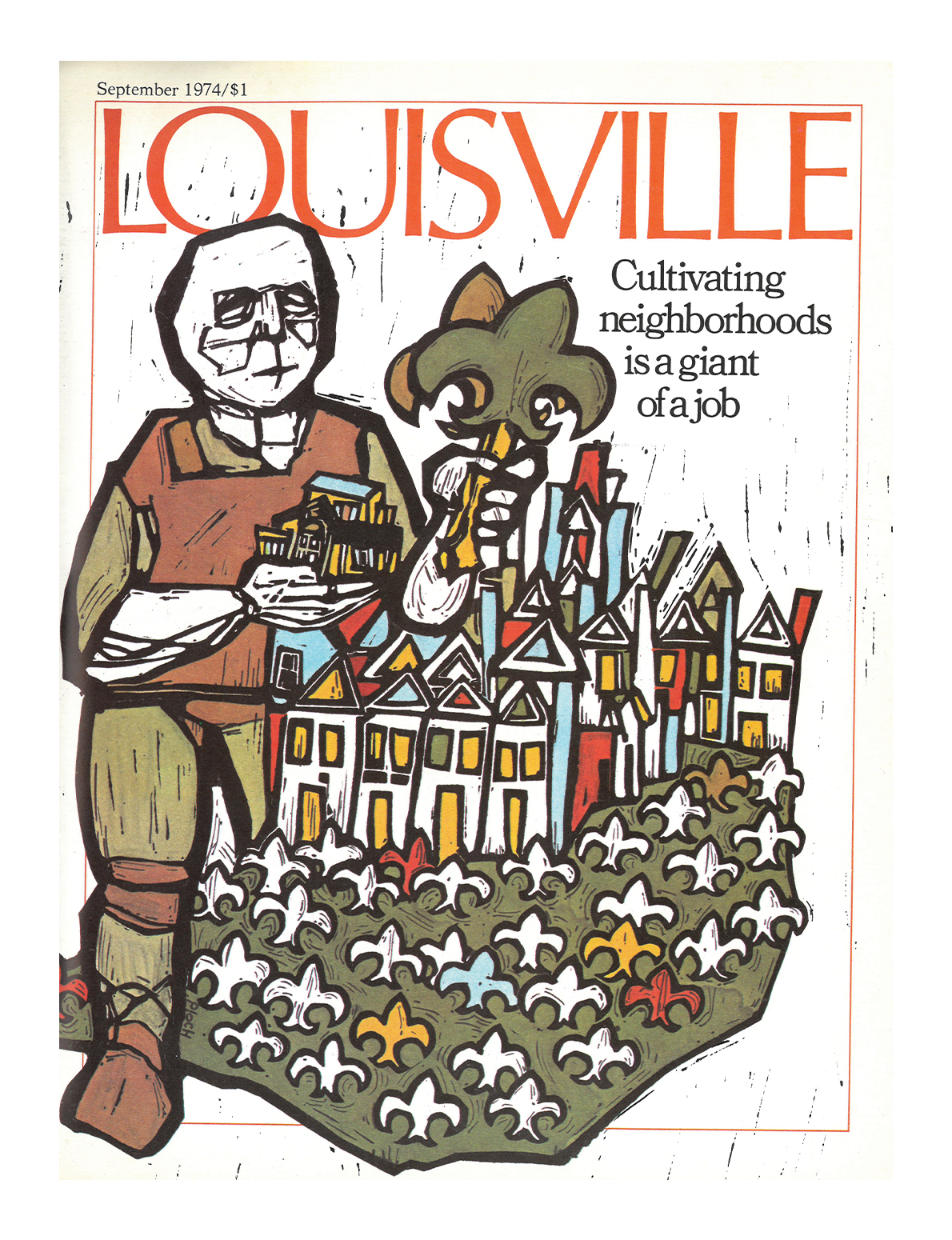

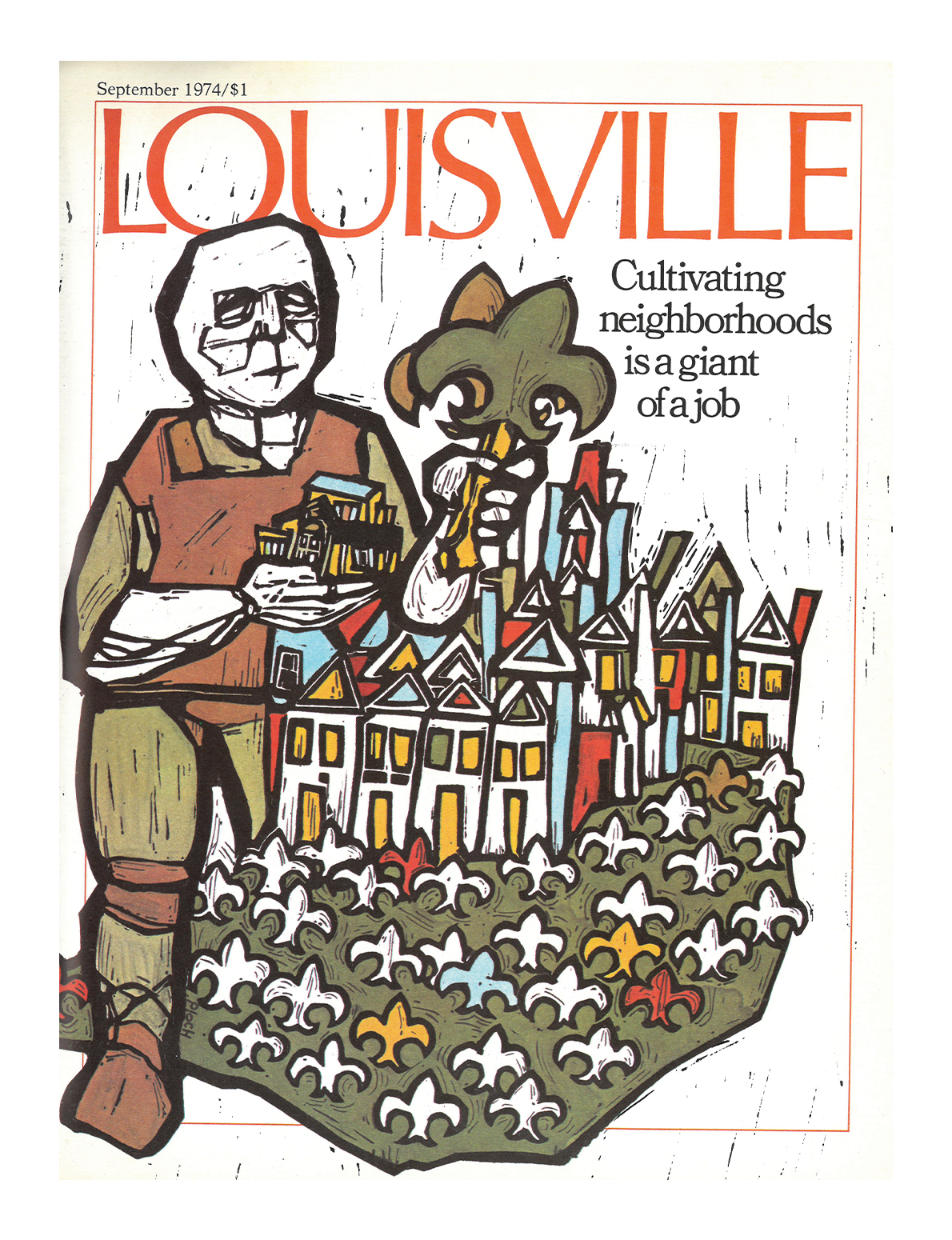

“Louisville has a real love of community that manifests at the neighborhood level. Our collective identity is really as a tapestry of individual neighborhoods, which is a more human-scaled way to think about place. This cover really speaks to that patchwork feel. It knits together the shapes and colors that make us richer. It also speaks to the stained-glass windows that are ubiquitous throughout the city. And since cultivating anything requires some heavy lifting, the giant makes a good metaphor for the work involved.”

.

“How about a haiku?

“Pulling at your strings

“Satisfaction guaranteed

“LOOAVUL outing.”

.

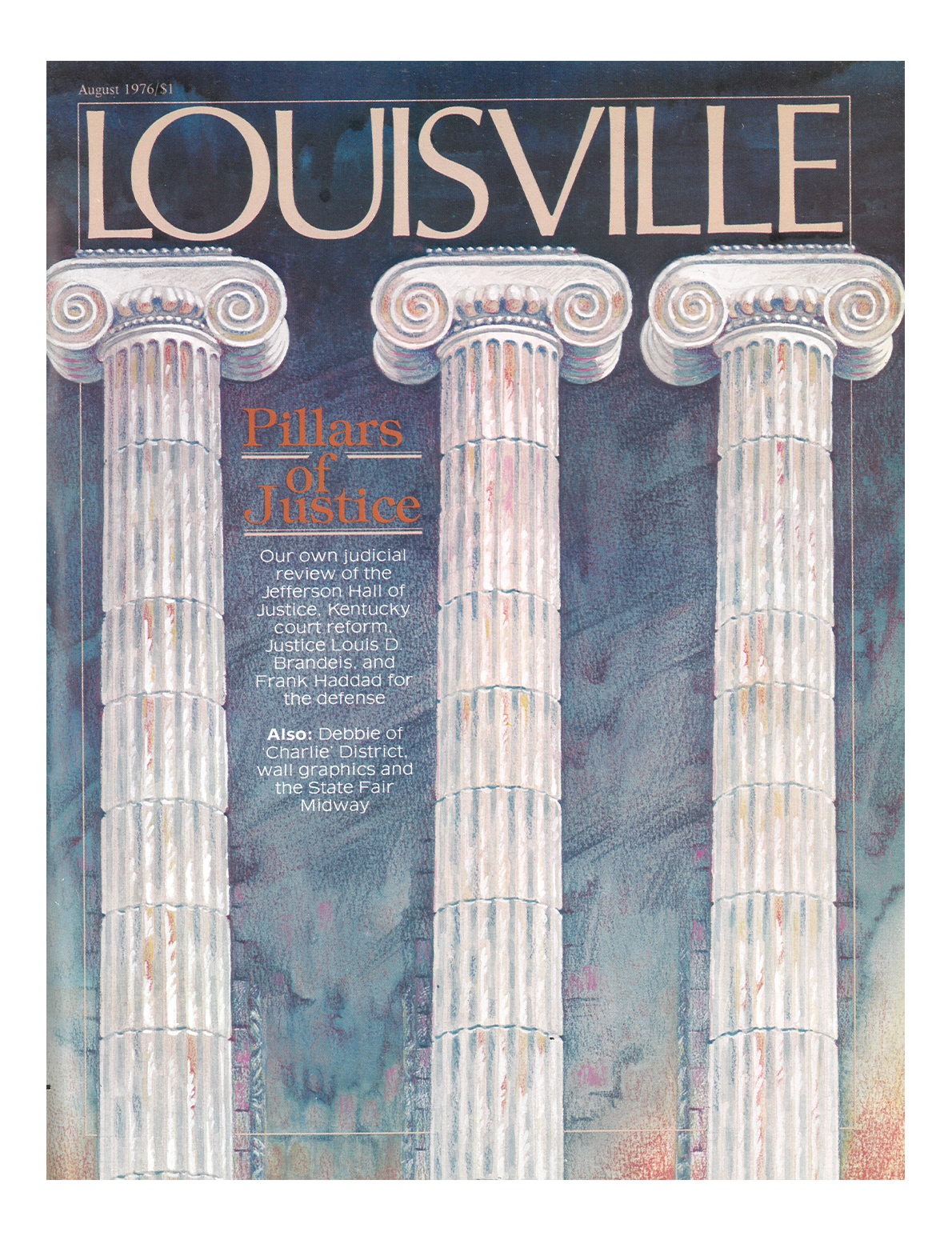

“Reconstructing Louisville back to a pillar community.”

.

“The dated nature of the cover photo seems to amplify its title question, as if to cast doubt on the value and relevance of school-board seats not only at the time but also — and perhaps to an even greater extent — today.

“And yet, nearly 44 years following the publication of this Louisville Magazine issue and after more than a year of a global pandemic that is still with us, having elected members of the community to steward the major governance decisions of their own school systems appears even more essential. Such decisions continue to matter greatly to its constituents. Consider the closely followed recent decision of the JCPS board to have students resume in-person learning this year as part of a hybrid model. The emotional 4-3 decision required hours of deliberation, with strong arguments on both sides debating an action that would affect more than 100,000 students — not to mention countless guardians, teachers, staff and administrators.

“In my view, however, even more important than the decision itself is the institution that requires those deliberations to be open to the public and to be led by elected members who answer to it. Regardless of where you fall on any one school-governance issue or another, the true value of a school board rests in its democratic structure and the transparency of its discussions, which act to earn and preserve the trust of the community it represents, as well as to safeguard and voice the needs of our most vulnerable families.

“Side note: The survey-like checkbox options in the lower third of the cover weakened the impact and the proposed question. They seemed to trivialize the value of a school board and thereby almost bias the viewer’s response, implying that the question could be reduced to one answerable by a fixed number of easily predetermined responses. Furthermore, by asking the respondent to select a single response, mutual exclusivity among the options has been assumed when that is clearly not the case. A selection of ‘My Children Are Grown,’ for instance, seems to convey the irrelevance of the question to some respondents, but parents of adult children — who are also, after all, taxpayers supporting the public school district — could very well still have strong opinions about the role of their local school board, especially in retrospect if their children had matriculated through and graduated from that school system.”

.

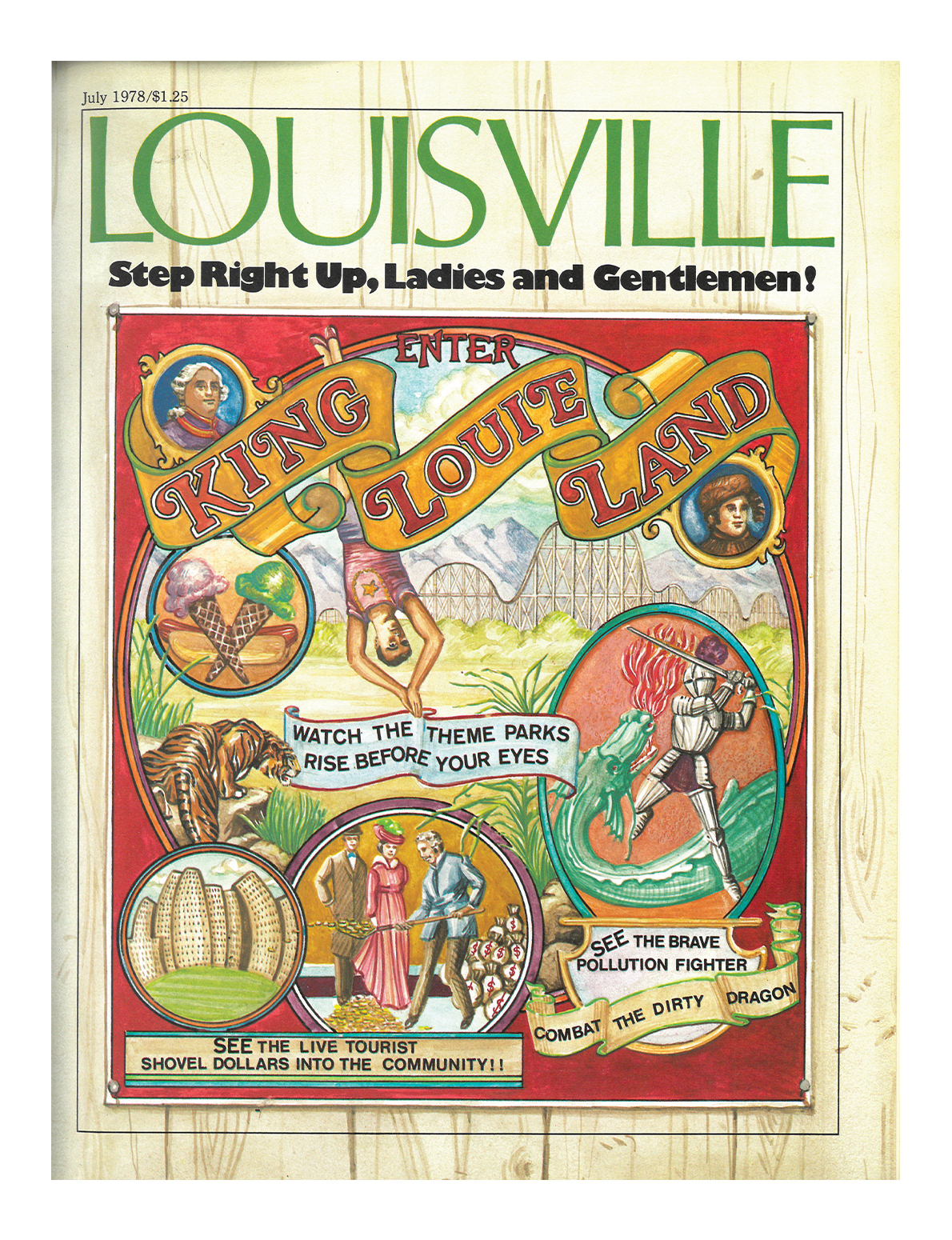

“This cover is from before my time, so I don’t know exactly what it’s referring to, but I’d guess it’s from right before we became the theme park capital of the United States of America. And it looks satirical, so I’m assuming the artist is skeptical that: a) We will one day become the ultimate tourist destination, and b) We will be able to eradicate whatever pollution, litter and air-quality problems are keeping us from becoming the new Orlando. This artist was dead wrong on both counts. Can’t win ’em all!”

.

“‘Swimmertime’ is an awful play on words. And is that model naked? If so, that makes this cover a bit cooler.”

.

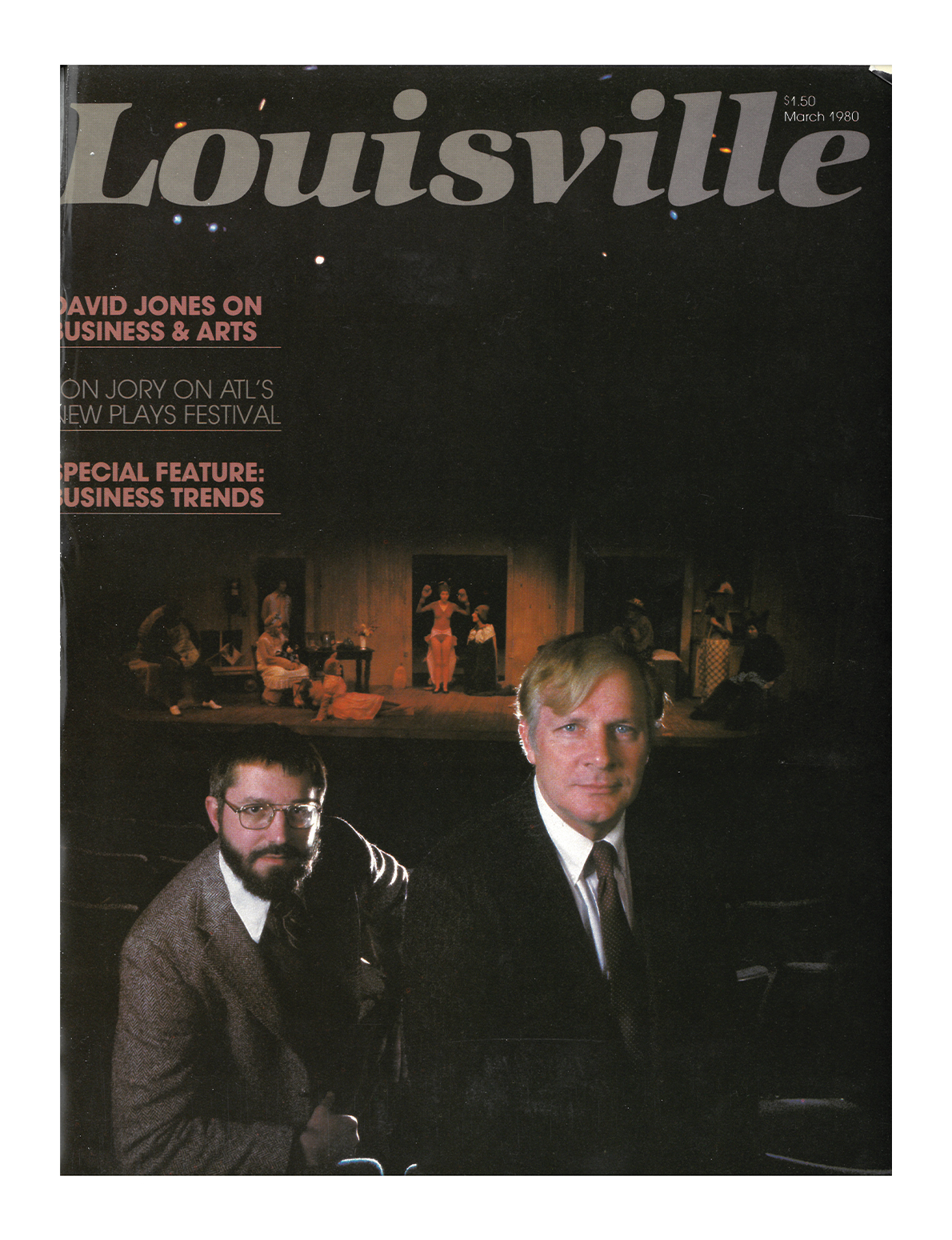

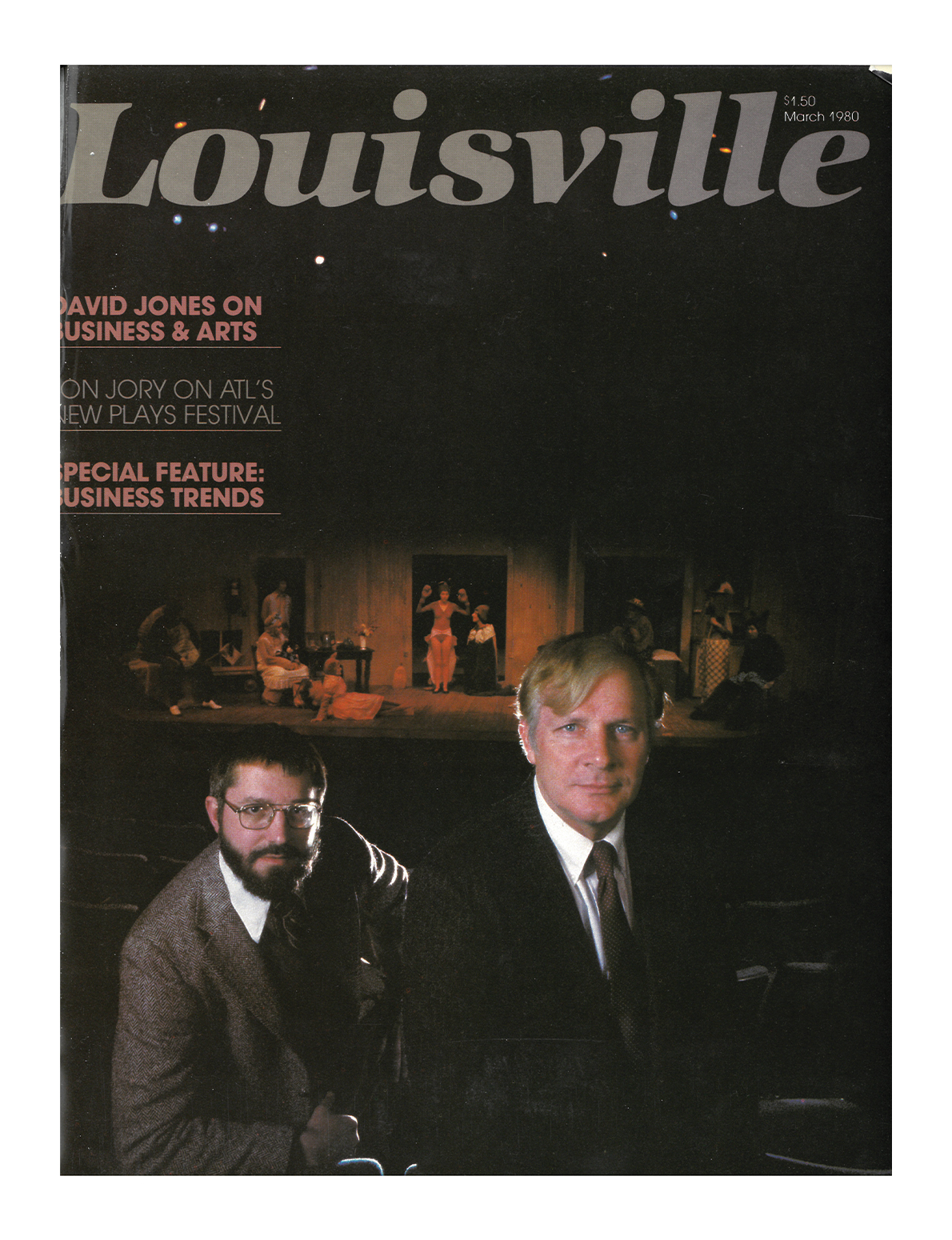

“Actors Theatre of Louisville’s Humana Festival of New American Plays has been a national trendsetter since 1976. When Humana co-founder David Jones and ATL creative genius Jon Jory appeared on this cover in March 1980, the festival’s local imprint was becoming huge, too. I remember it well: As a newlywed spouse of a board member, I attended openings, dinners, parties and all nine new plays, including John Pielmeier’s Agnes of God, which went on to be a hit movie with Anne Bancroft and Meg Tilly. My personal favorite of that festival was Kent Broadhurst’s They’re Coming to Make It Brighter, about a pair of Black elevator operators on Christmas Eve, marking their last night before the building renovators were to install self-service elevators. For years, whenever some new trick was being played on the building where I worked (the Courier-Journal), we’d smirk and say, ‘They’re coming to make it brighter!’ So many amazing nights of new plays, hordes of international theater and media people gathering. Sadly, Covid has sidelined the festival, but let’s say with confidence for next year: ‘They’re coming to make it brighter than ever!’”

.

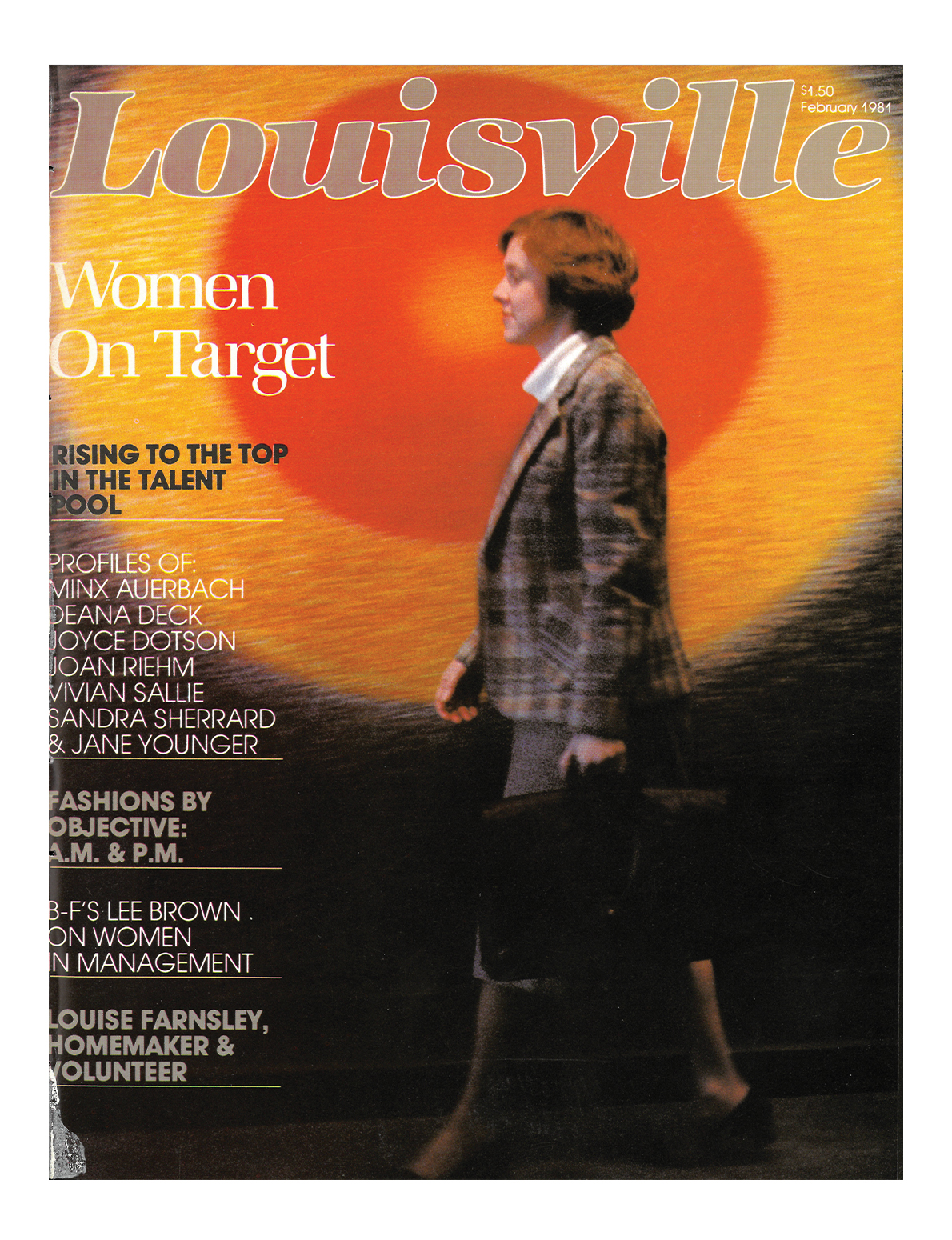

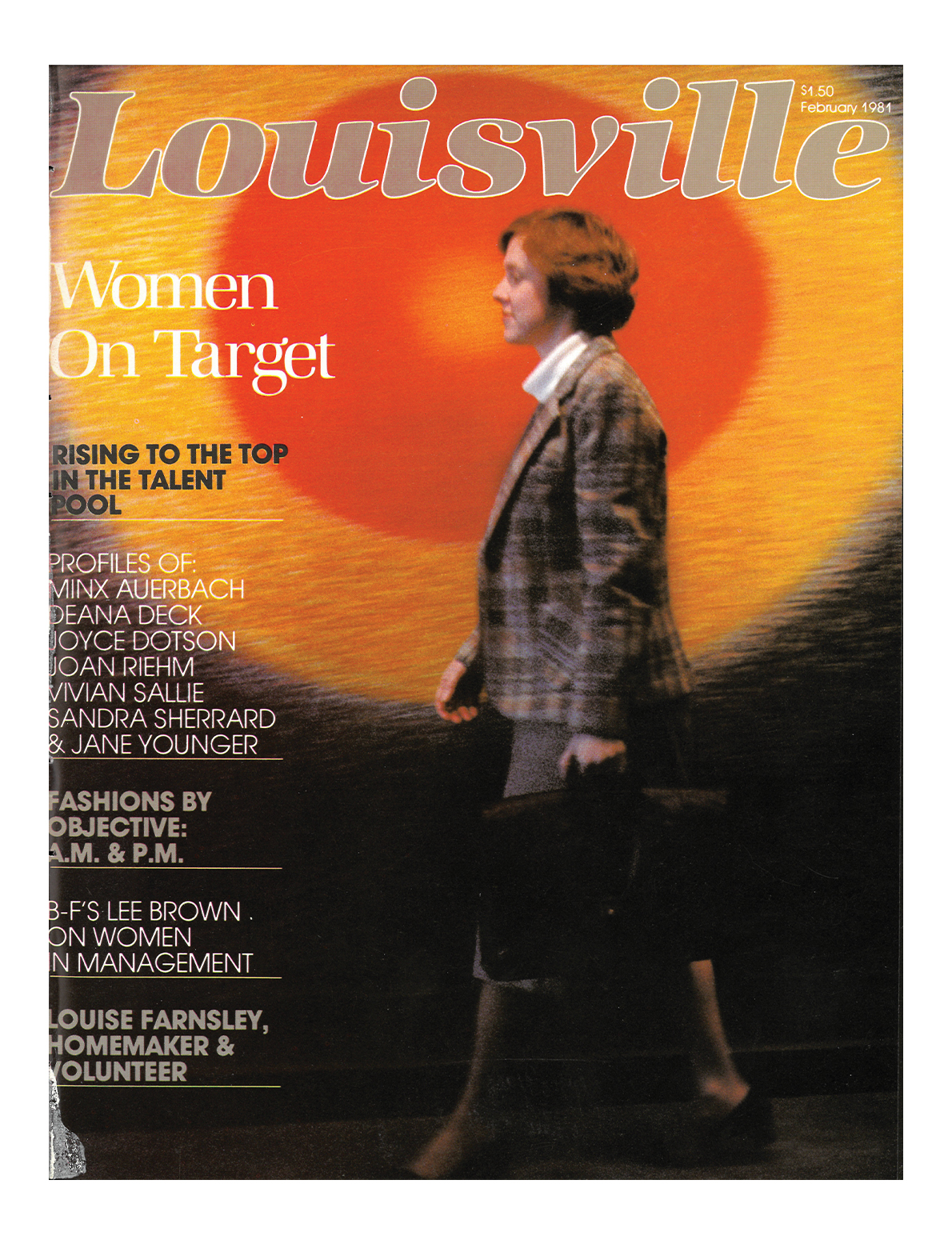

“This makes me think of women who taught collaborative divorce strategy at least a decade ago as related to Zen archery. The Western version is probably best explained as intuition or being ‘in the zone’ when you solve intractable problems while you aren’t thinking about them.

“‘Women on Target’ begs the question: What target?

“As tech eclipses live human interaction, and groupthink overpowers critical thinking, intuition is a stealth skill women use to make decisions and lead. What the world needs now is women to lead it out of the valleys of economic despair, and away from an exclusive reliance on data, into radical change. Intuition, empathy and taking care of the community are evergreen skills that will help us live into solutions to what ails us. If that’s the target, we are on it.”

.

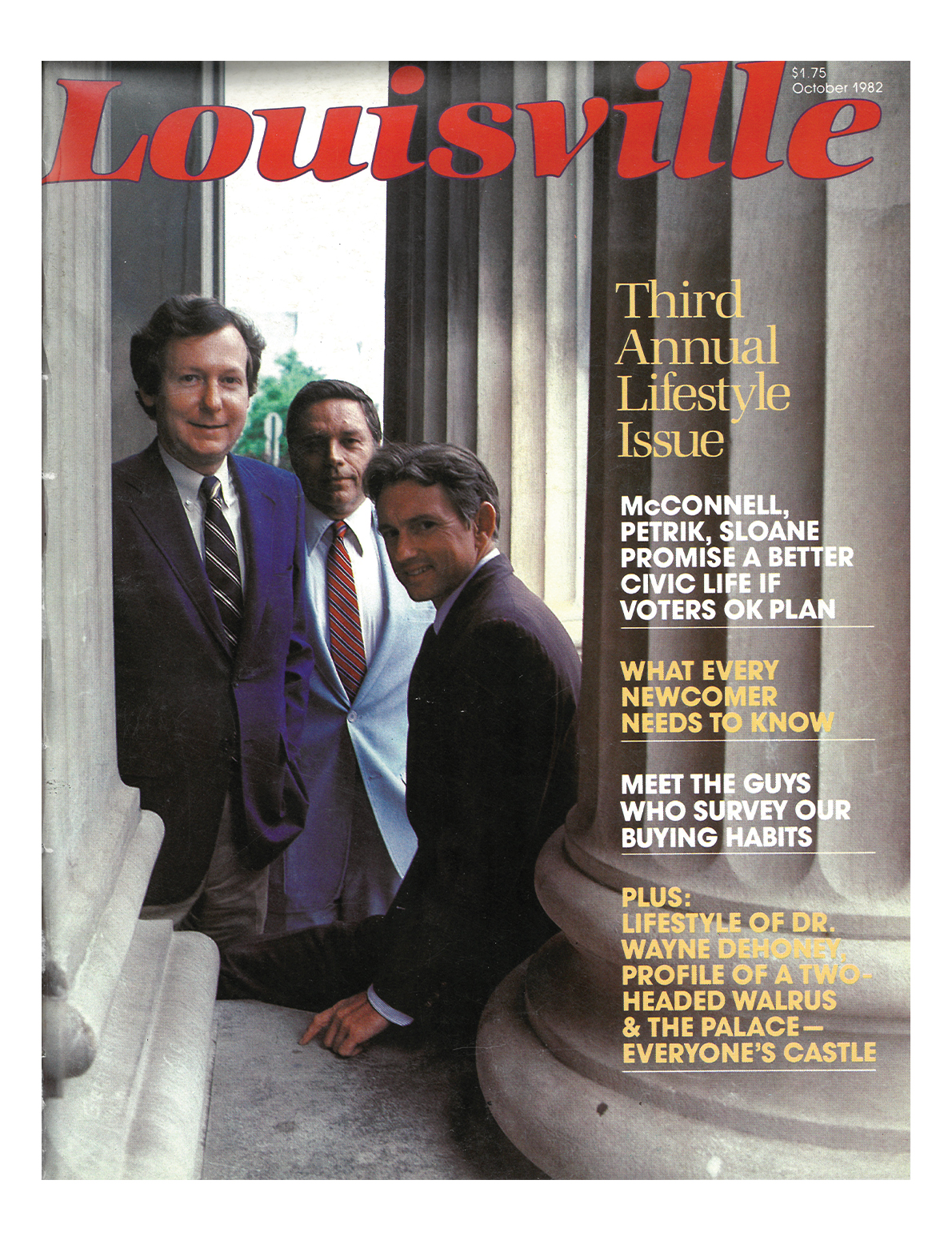

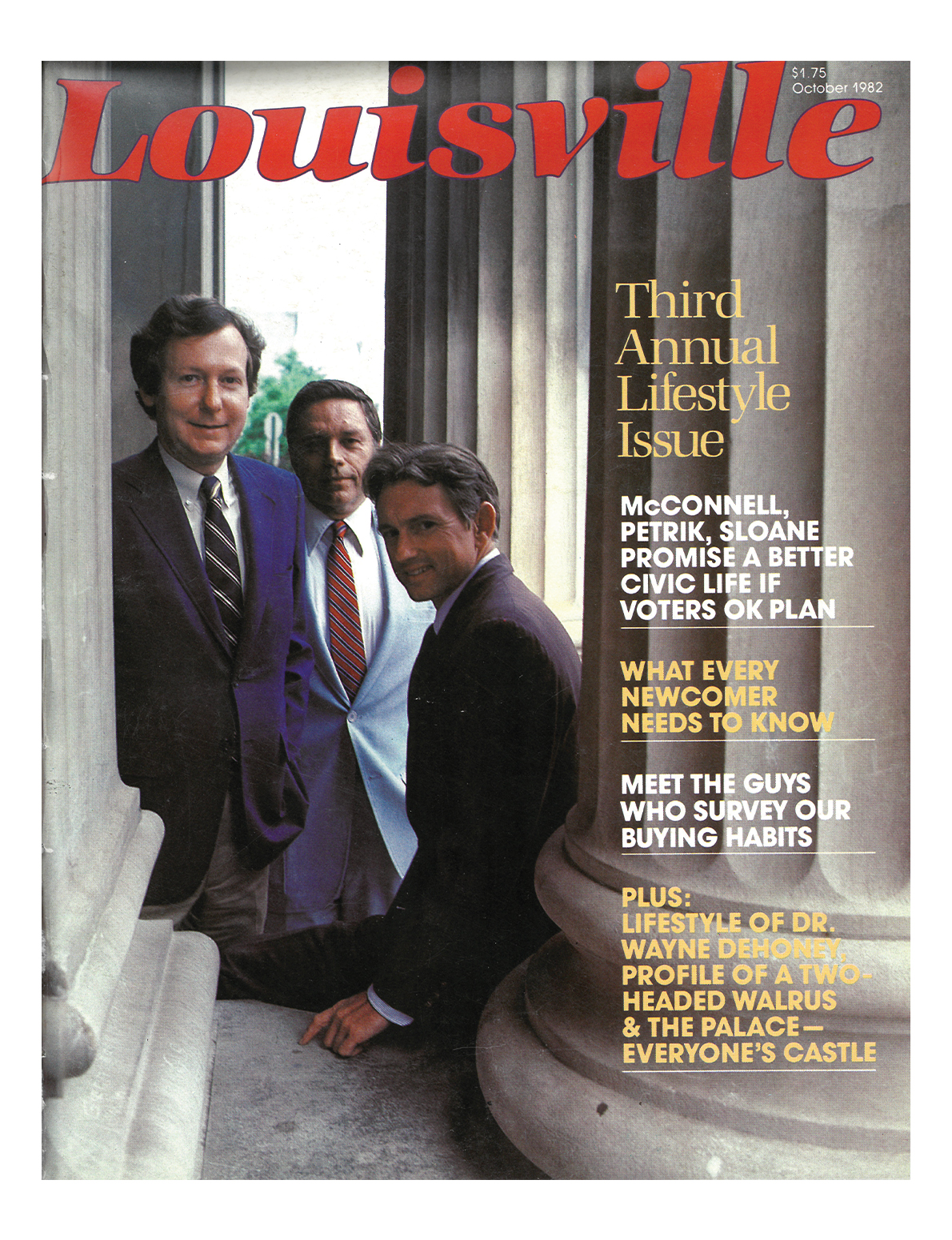

“How quickly the future becomes the past. And has civic life gotten any better?”

.

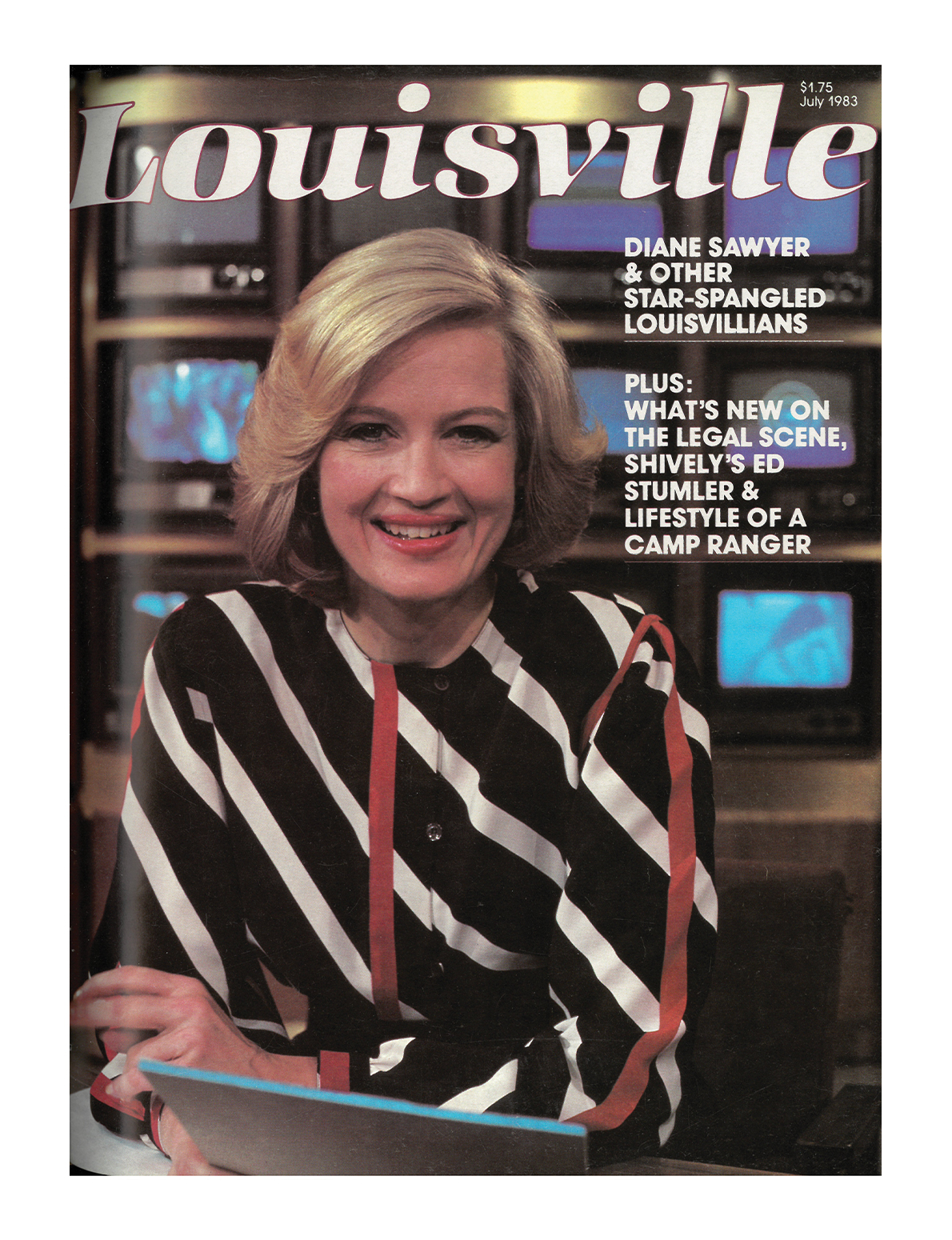

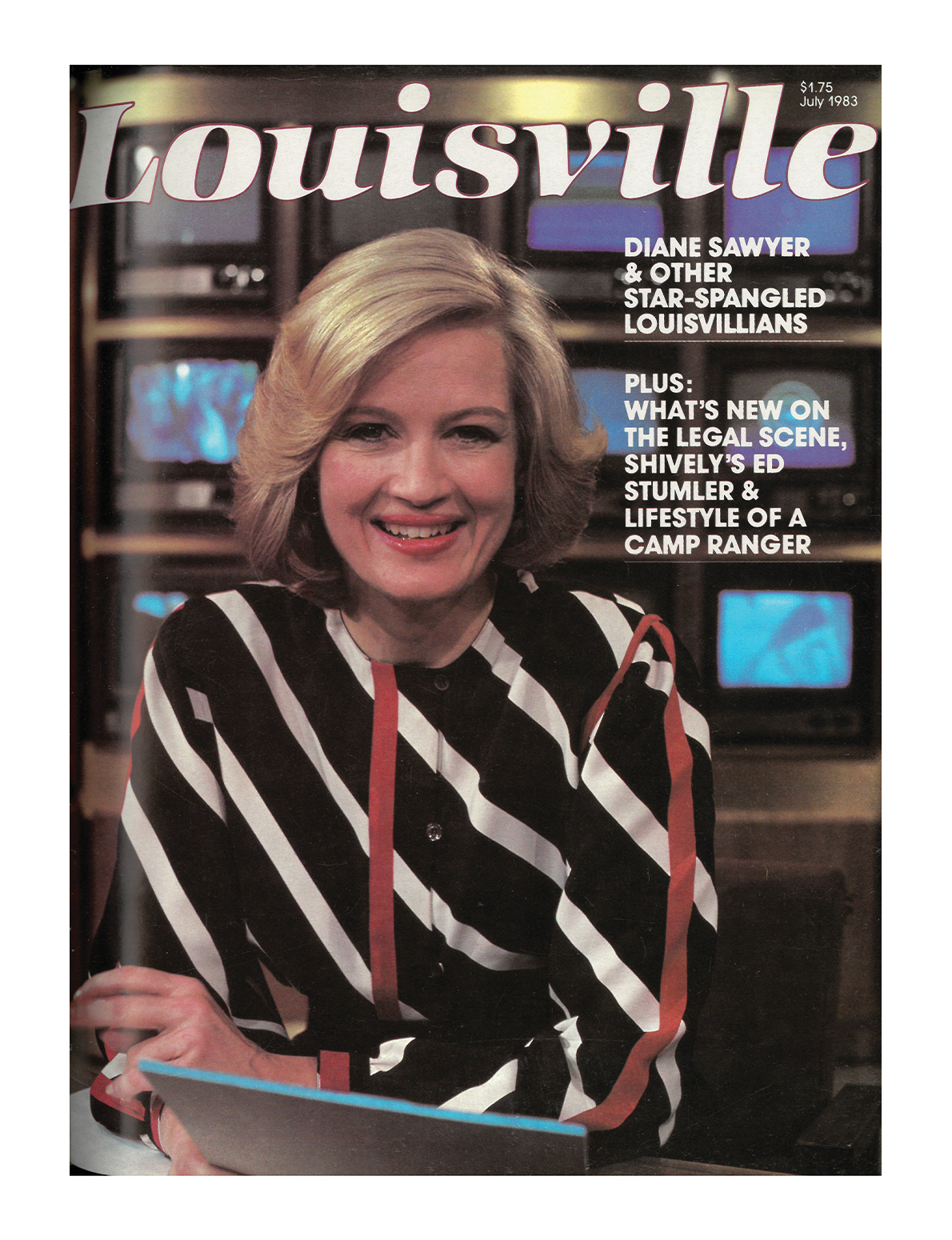

“Louisville native Diane Sawyer is the quintessential American television broadcast journalist. Her talent has been on full display for the world to see: ABC’s World News Tonight, Good Morning America, 20/20, 60 Minutes and more. I have always enjoyed seeing her work, but I was most proud to see her front and center on the cover of Louisville Magazine as a Kentucky girl at the top of her game. It’s inspirational for anyone who has had a dream and wondered if they had what it takes to get them there.

“I remember meeting Diane Sawyer at the wedding of former (WAVE-3) Troubleshooter Eric Flack, who is her godson. Sitting in the crowd of friends and family, I closely watched this striking blond woman a few seats in front of us as I thought, ‘Boy, she looks just like Diane Sawyer!’ Someone from the newsroom whispered, ‘Remember, she is Eric Flack’s godmother?’ I began to fangirl out because this iconic journalist was feet from me. I love Eric Flack’s ‘Bubbe’ (grandmother), and Diane Sawyer was sitting at her table. As I hugged Bubbe, she sweetly introduced me to the Diane Sawyer. I’m not much on weddings, but this one was a real treat!”

.

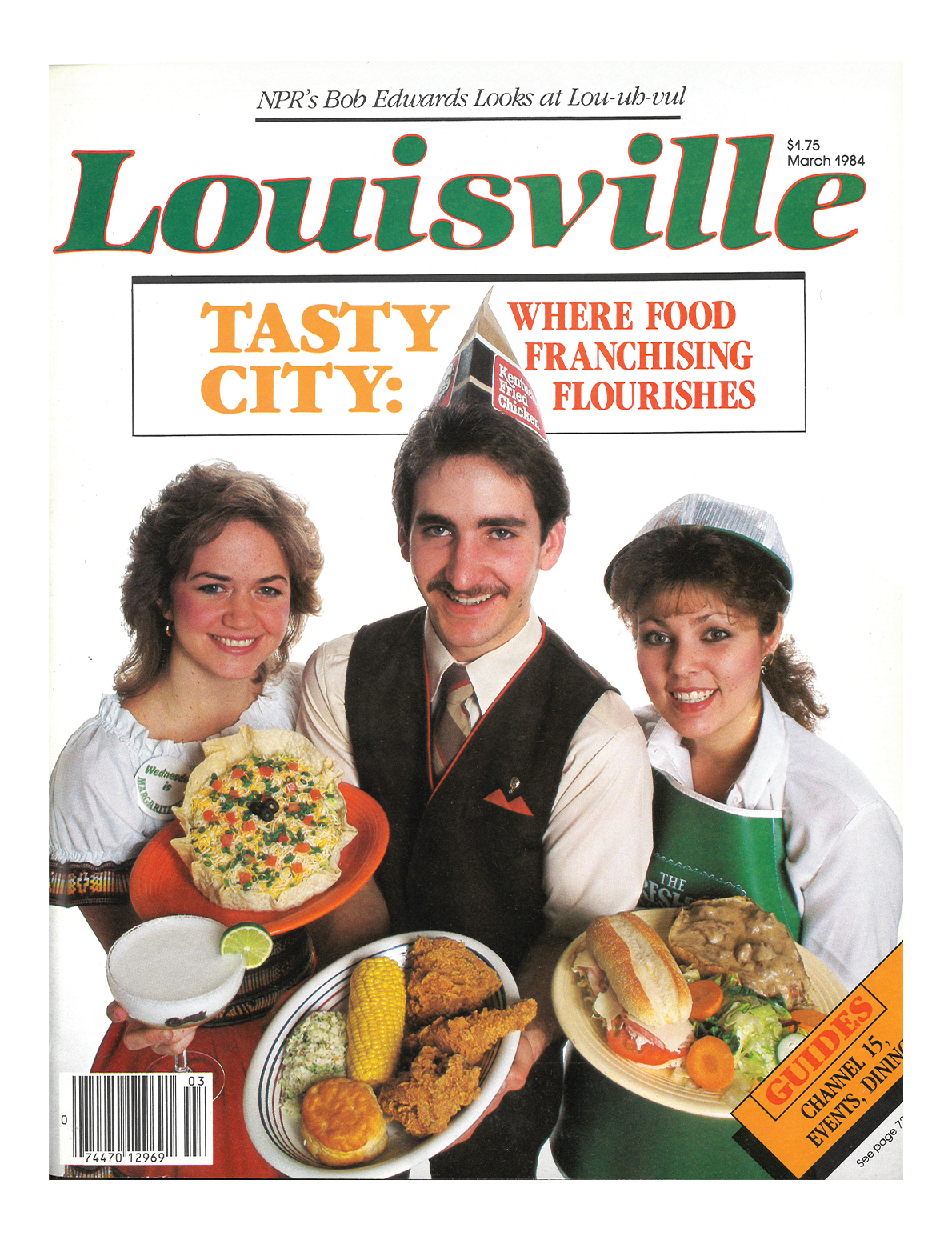

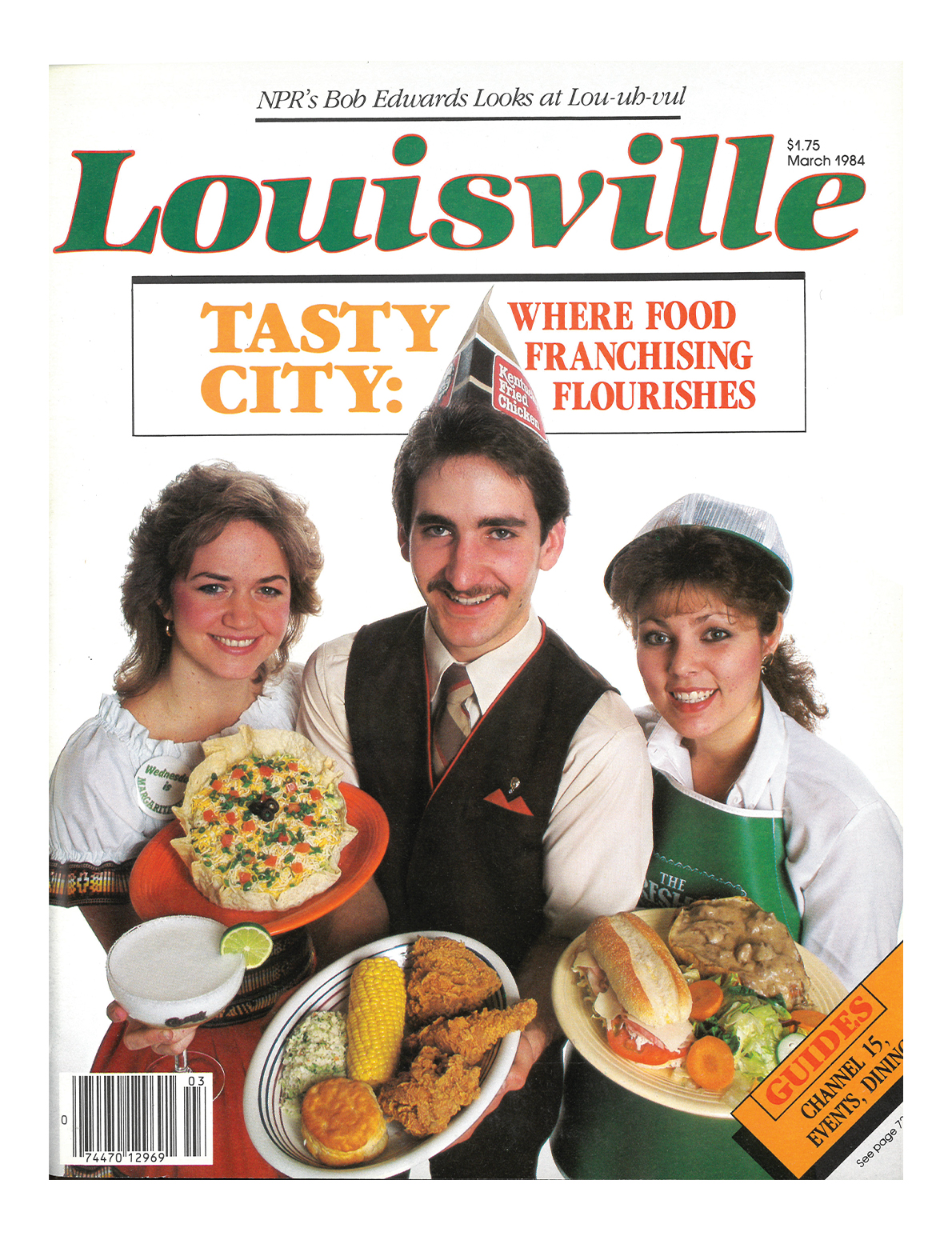

“This cover honestly makes me happy ! The age of thin mustaches, perms and ridiculous, gimmicky restaurant attire! What’s not to love? Not to mention the joy and excitement I get from the intense evolution of the food revolution. I was born in ’86 and remember the days of single-origin cuisine and zero plate presentation. Thank God we’ve embraced multicultural fusion. Long live Louisville’s Meritage cuisine!”

.

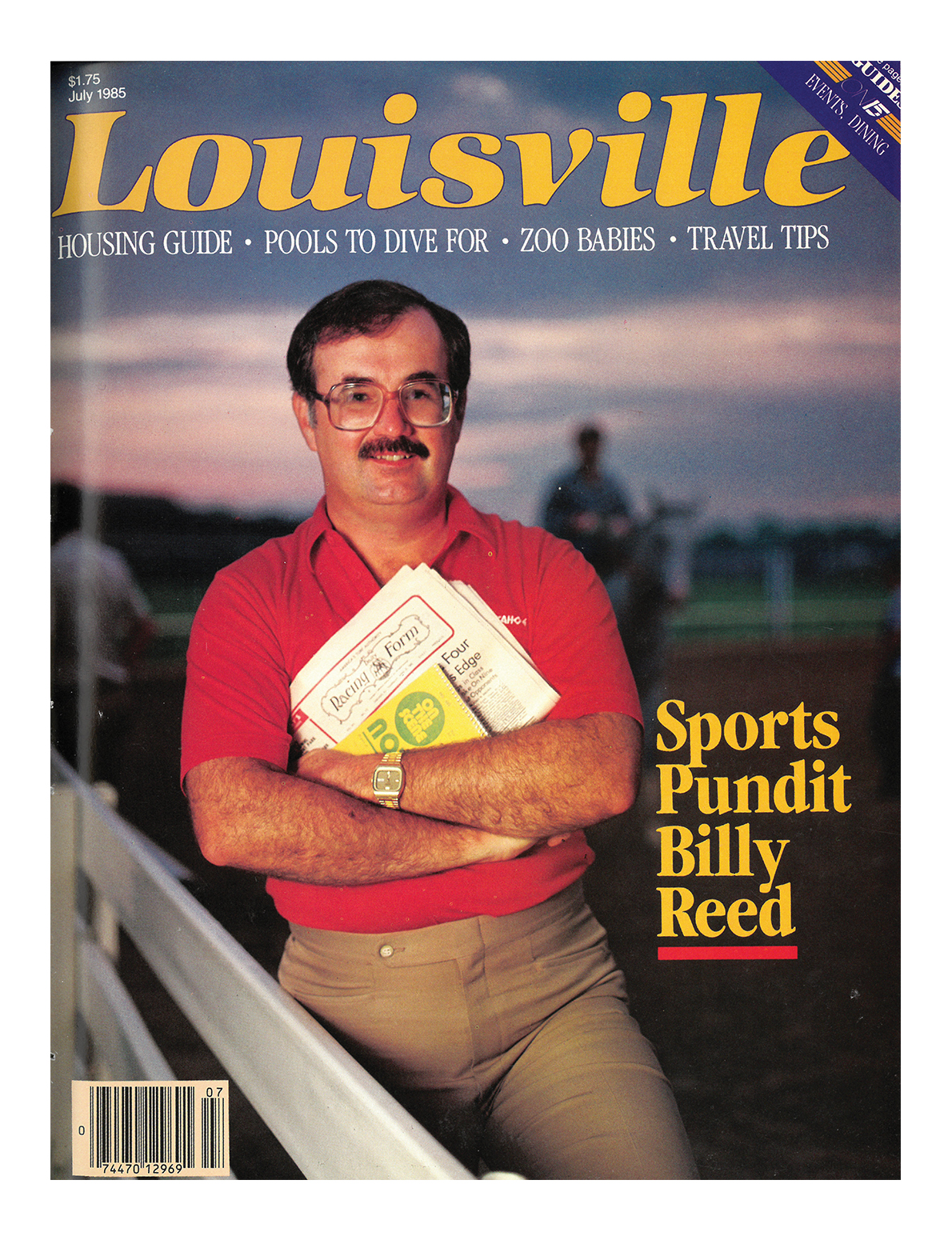

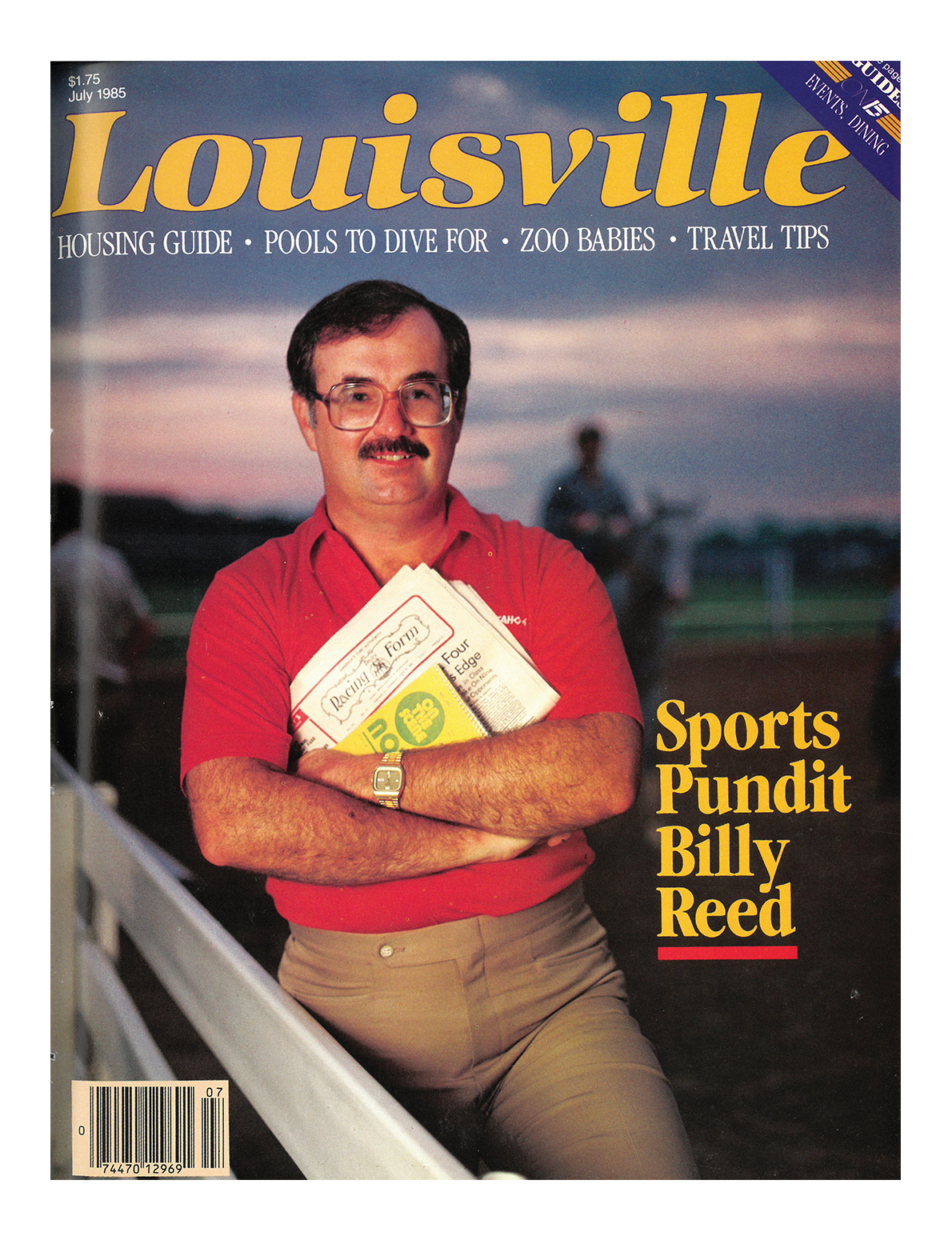

“From the Sansabelt slacks to the old reporter’s notebook, this is a period piece to be sure. But there is something timeless about mornings at Churchill Downs. The sights and sounds and smells remain much the same today as they were in Billy Reed’s day, and for decades before him, dating to when the Kentucky Derby became a great American sporting event in the late 1800s. Billy, who worked for the C-J and Sports Illustrated, did as much as anyone in the latter decades of the 20th century to keep alive the romance of the race, and what it means both to the sport of horse racing and to the city of Louisville. The Derby is Louisville, and Billy loved — still loves — the Derby as much as any Louisvillian.”

.

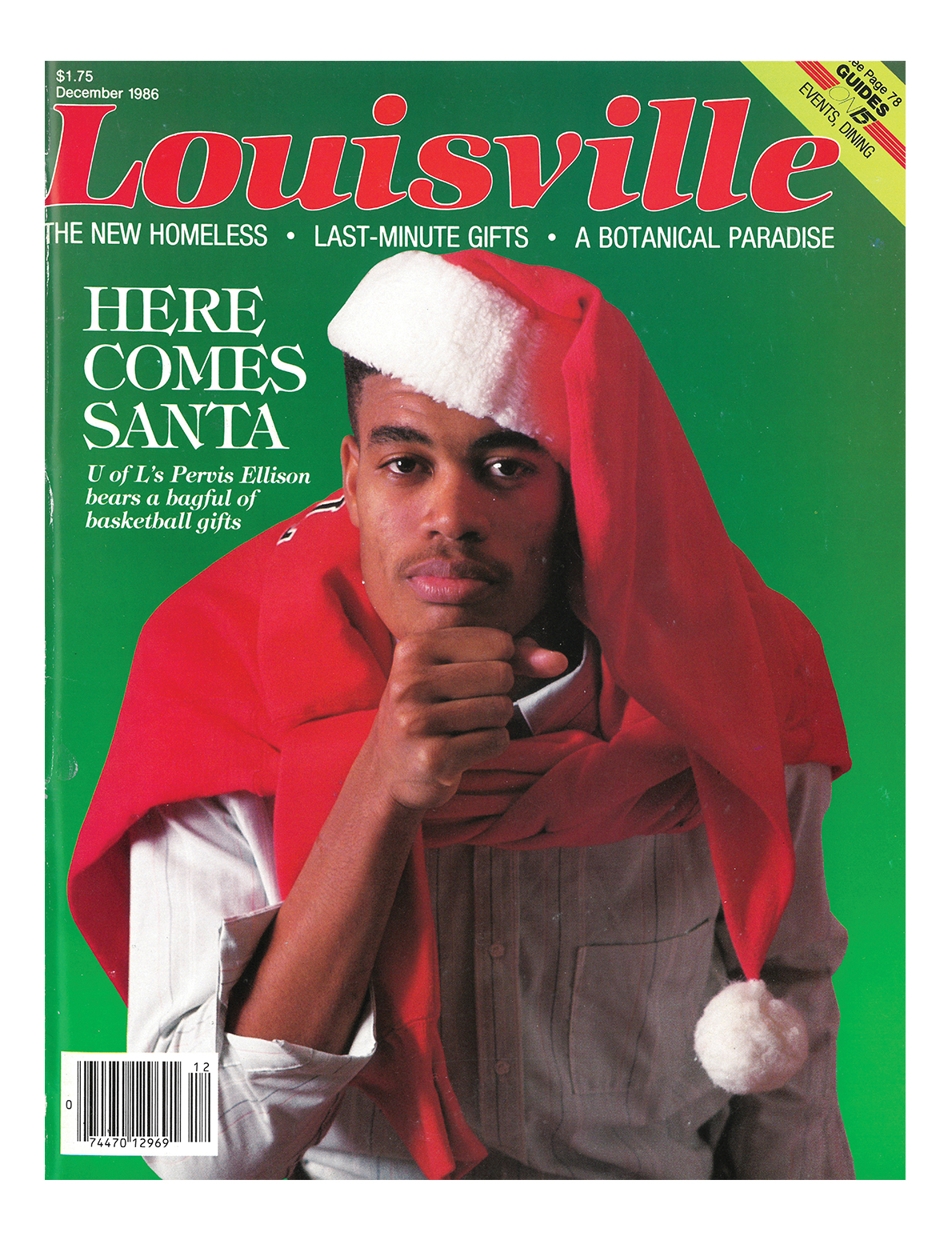

“If I could take a trip back in time, I’d certainly make a stop in 1986. That shot of U of L basketball player Pervis Ellison reminded me when Louisville was The Place To Be in college basketball — two national titles and four Final Fours in seven seasons. Pervis likes to remind me that he, too, could have left for the NBA after one season but stayed three more years. College basketball meant something different then — to players and fans.”

.

“The eternal question: Is Louisville Southern? The plantation porch would say yes, but I’ve always thought that if the city were actually Southern it wouldn’t need to wistfully ask the question each May. And the wistfulness says that we’re only seeking out the romanticized version of the South — with none of the baggage. Is Louisville Southern? Perhaps it’s not the seersucker suits we should look to for the answer, but the conflicts over Confederate monuments and the perpetuation of a Ninth Street divide.”

.

“Ben Richmond, the shoulders on which I stand. He was a man, as my predecessor, who fought with a velvet glove. He was a friend to many, but he quietly made more enemies than this city wants to admit. He pushed for better, he demanded more, but he didn’t have the benefit or the curse of social media, so many people were not privy to his struggle or the times he was condemned for pushing back. He made room for my leadership. He made room for a lot of us. In fact, he is still making room and opening doors. It is important to honor and respect his style of leadership and his sincere desire to pave the way for next generations. In my view, until he takes his last breath, he will be ‘point man’ for the Louisville Urban League. His legacy is etched in time and space eternal.”

.

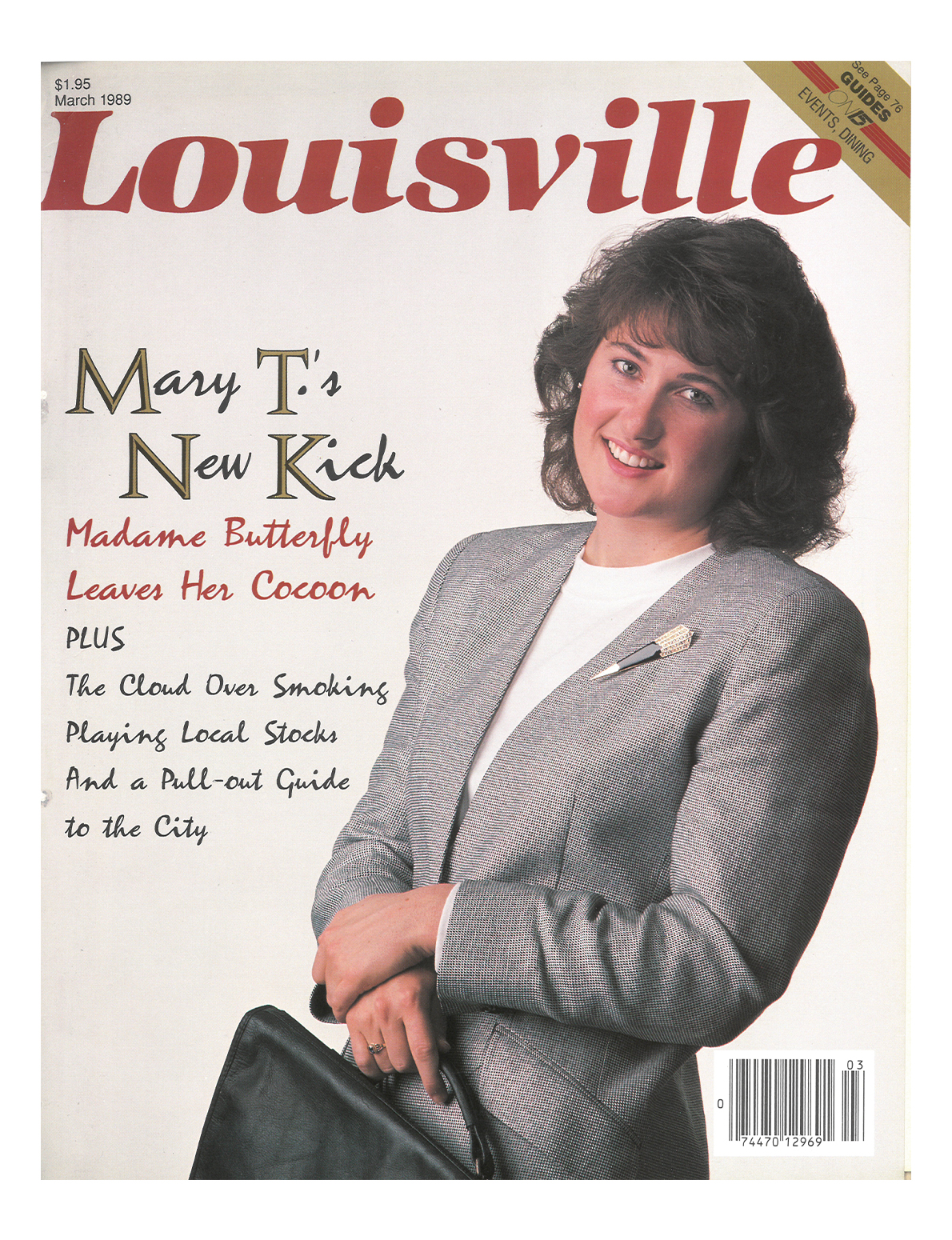

“We should be proud of the success of Mary T. Meagher (the butterfly swimmer who won three gold medals at the ’84 Olympics). We should celebrate the achievements of strong women. They show us new ways of being. They give us a boost when we need one. We can lean on them to avoid falling, and when we trip over our own two feet, they are the best people with whom to laugh.”

.

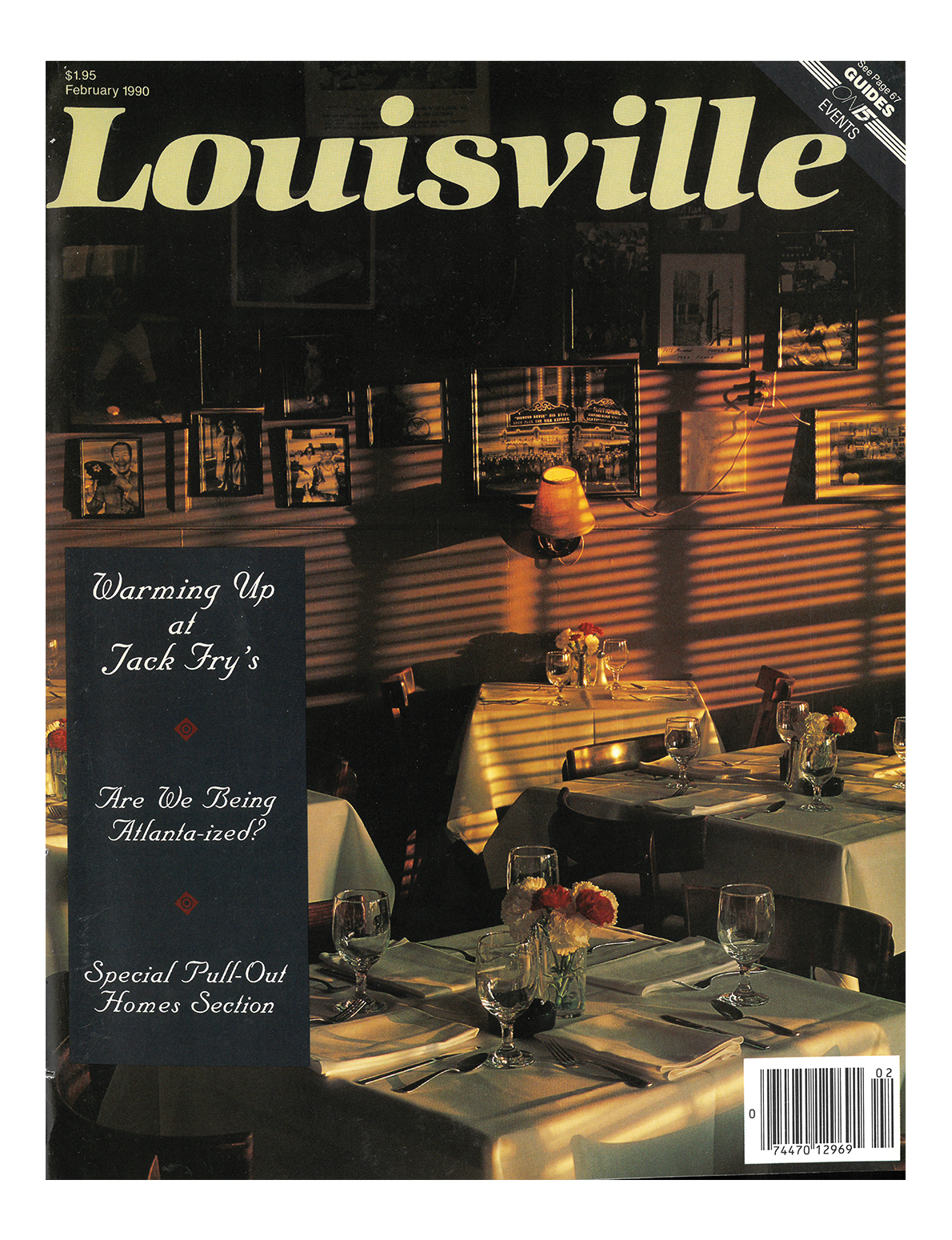

“My first thought is that it looks as though it’s full of memories — but eerily quiet, peaceful and serene, unknowing of the wild ride that lies ahead.

“I remember many days during the closure of 2020, sitting alone staring with disbelief into the sad and empty dining room, seeing those same streaks of life-giving, hopeful sunshine piercing between the blinds, striping the walls and illuminating the photographs. I could feel the confused, abandoned space craving excitement, energy and life, just as we all are right now.”

.

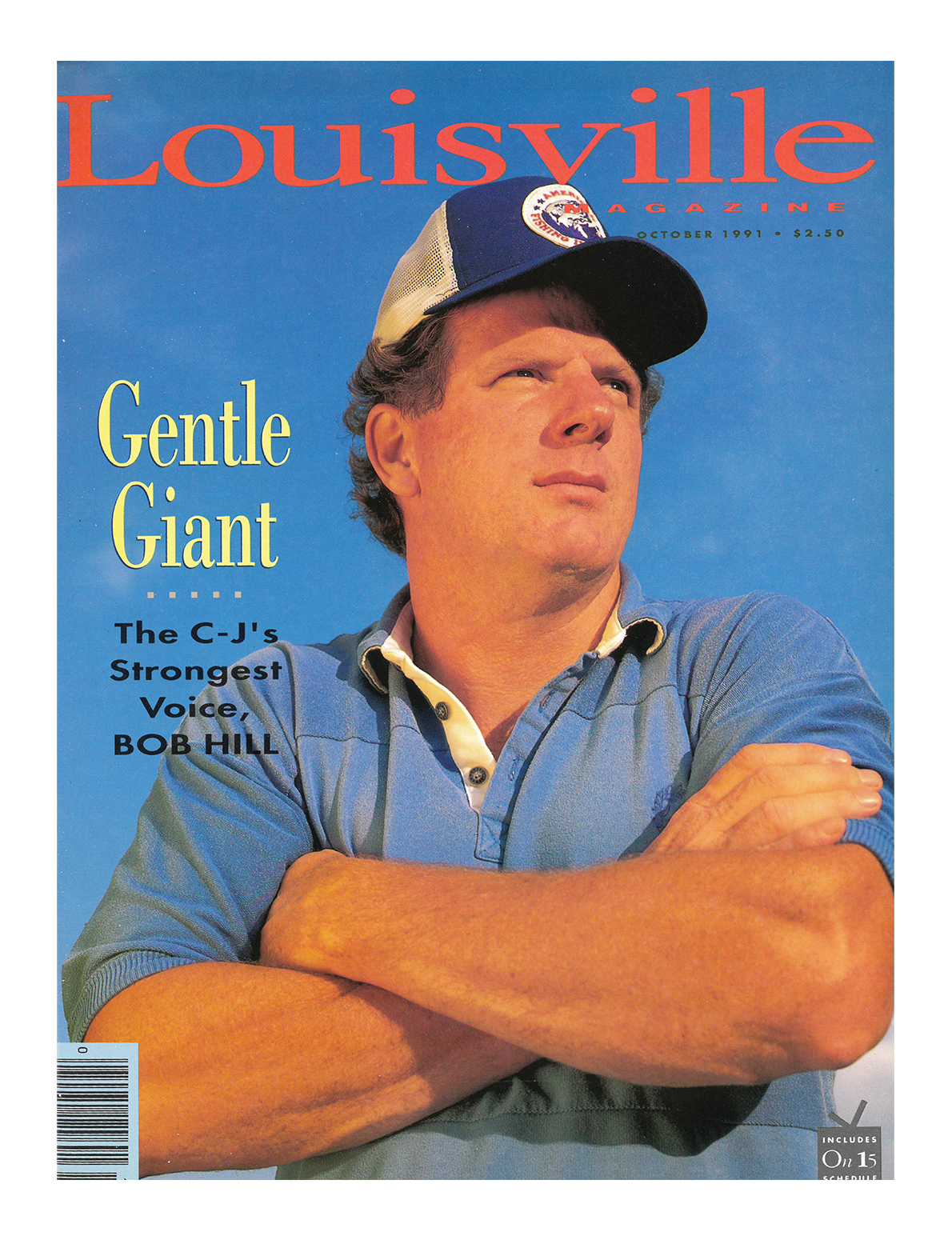

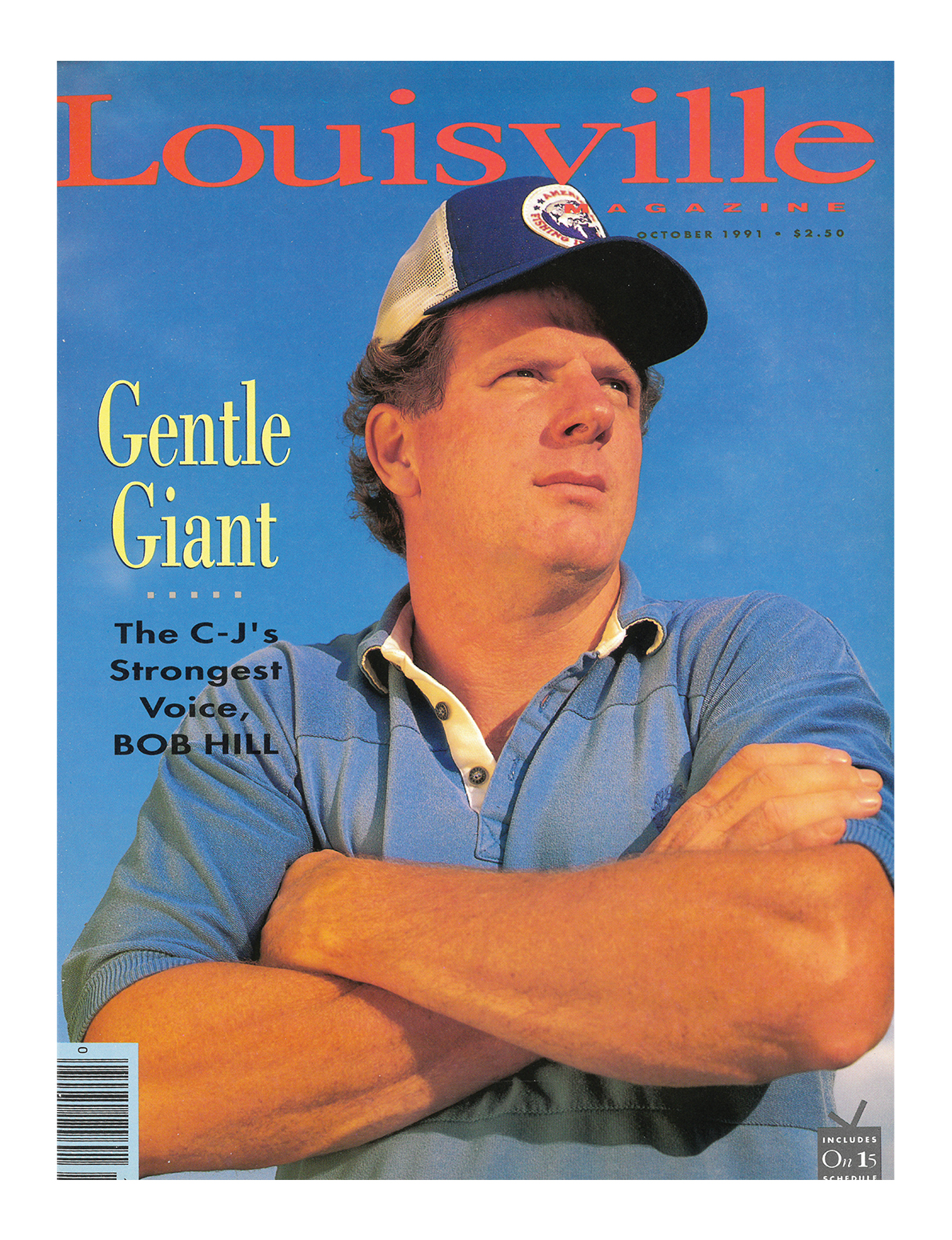

“Bob Hill has always been such a fascinating guy — a Renaissance man of sorts. Extremely eclectic in his interests: a sports fan, a gardener, a person passionate about politics and public affairs. I feel like that gave him the perfect perspective as a column writer. I founded LEO in 1990 and began writing a weekly column, which Bob had already been doing for years at the Louisville Times and then at the Courier-Journal, so he became somewhat of a role model for me. You always got the impression that Bob considered himself an everyman. He never took himself too seriously, and he really didn’t take his subjects too seriously, whether they were Louisville’s power brokers, wealthy elite, elected officials — whoever. He didn’t defer to anyone just because of the position or power they might have held.

“In his years at the papers, he had a unique ability to humanize every issue and knew how to connect what might be going on in City Hall or in the business community at that time directly to readers and their lives. I’m not sure many columnists really take the time to do that anymore. So many these days are just looking for clicks or pageviews. I think we’d be better served as a people if we had a few more Bob Hills at every publication.”

.

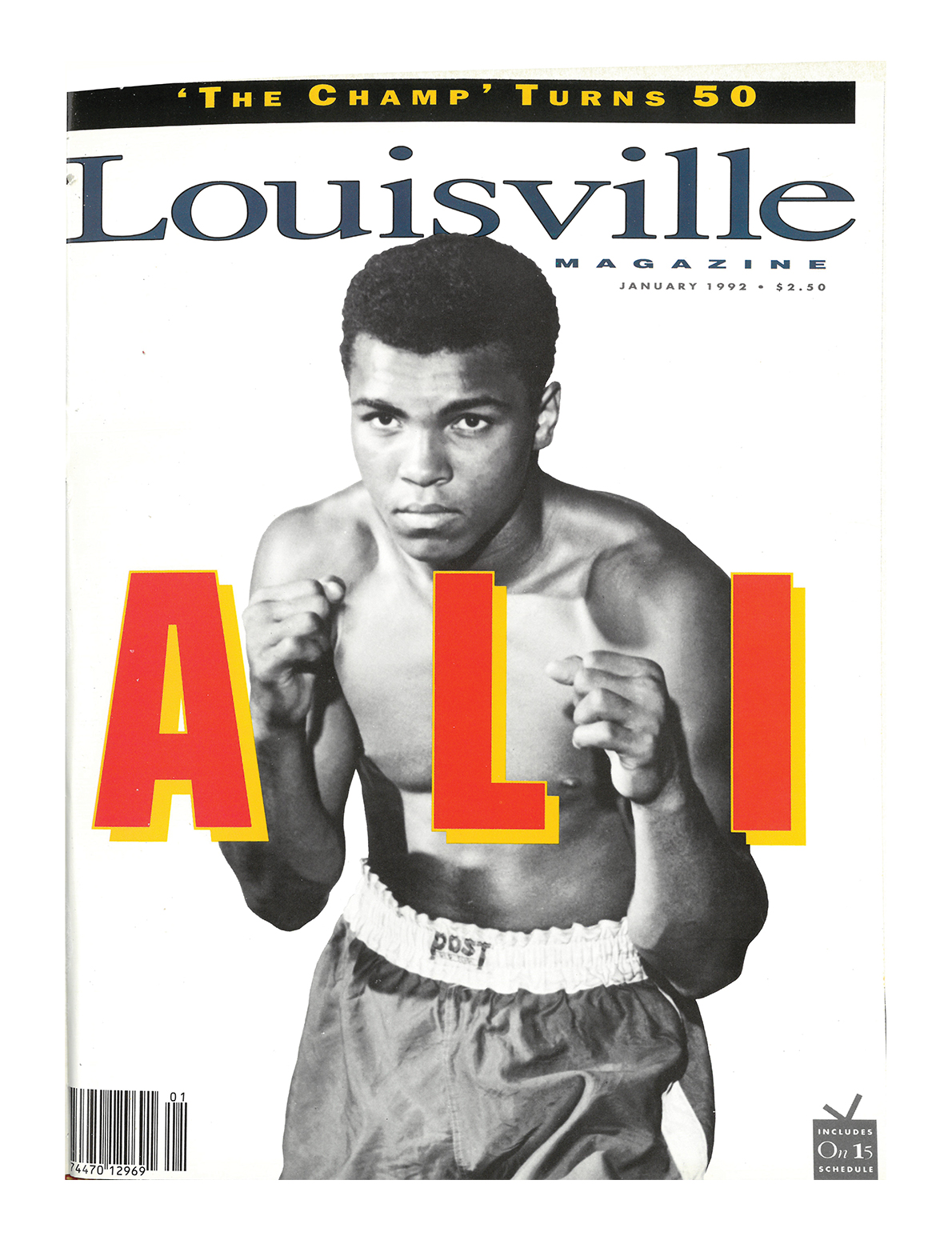

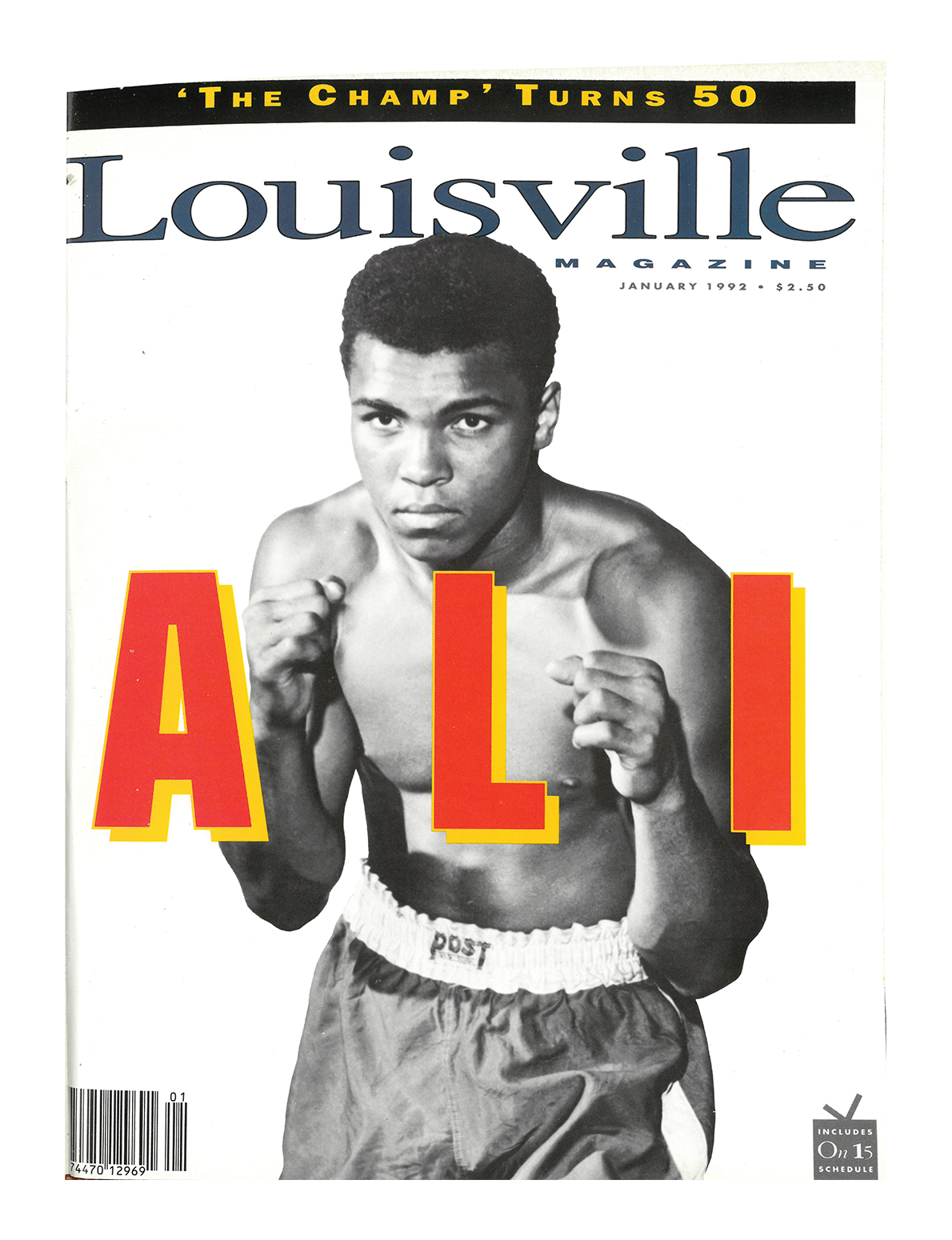

“I met Muhammad in the early ’80s. He was still fighting but was certainly at the end of his athletic career. I was 20 years old at the time — the age of Cassius on your cover — and I had managed to gain an invite to a small Derby party that Muhammad was scheduled to attend. He was stumping for John Y. Brown, who was attempting to become governor of Kentucky. I remember being so nervous and hesitant to approach the Champ. When I am unsure of myself I attempt to use humor, so I leaned into his space and, in my best impression of the sports broadcaster Howard Cosell, said, ‘Well, Muhammad, you could be the greatest heavyweight of all time.’ Muhammad smiled and replied, ‘Howard Cosell gets paid to do that; what’s your excuse?’ He then asked me to sit with him, and he told tales for a good 30 minutes. When he was ready to leave, he asked me to walk him to his car. It was during our walk that he squared up, put up his dukes and starting playfully throwing punches at my head. He said, ‘Let’s see what you got.’ I was so busy smiling and ducking I was way too overwhelmed to offer any resistance. He smiled and asked me to write down my address. I borrowed a pen from his driver and Muhammad stuffed my address in his jacket pocket. His last words were, ‘John, I am coming to see you when I visit my mother.’

“Two weeks later, he showed up at my house. Vintage Muhammad.

“We developed a 35-year friendship, and I traveled to Europe, Canada and many U.S. cities with him. (For his 50th, mentioned on the cover, I was in Los Angeles with him for a birthday celebration that was later aired on television.) I cannot articulate how much he influenced my life. An injection of positivity and inspiration. I witnessed the power of kindness. The Ali Magic.

“The cover is of a completely focused young fighter, determined to become a champion. I look at this image and feel hope for the boundless possibilities of a young person with a specific goal and an optimistic heart.”

.

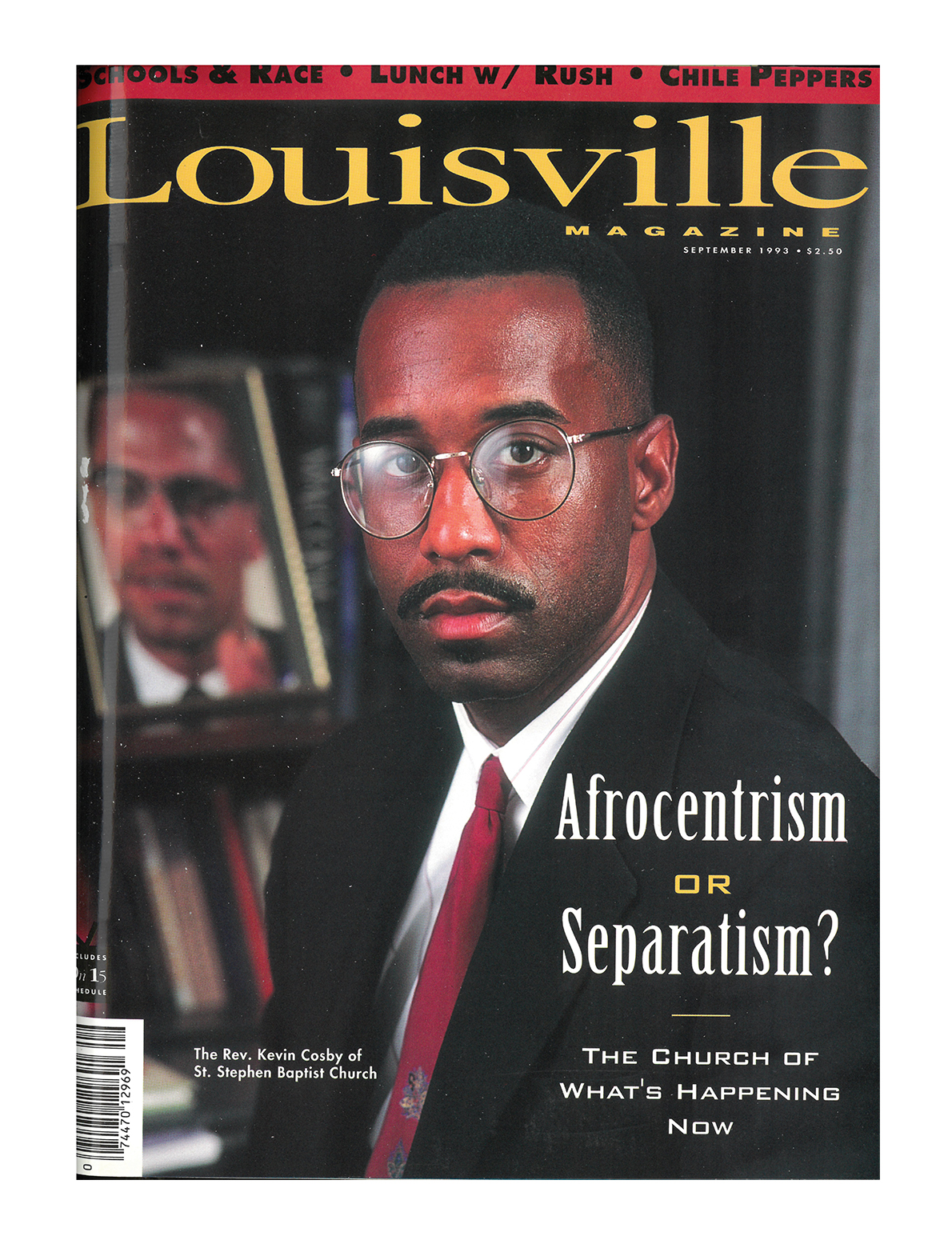

“I was 15 months old when this issue of Louisville Magazine was published.

“When the average American thinks of presidents, they might think of the first one, George Washington, or the Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln. They might even think about our first Black president, Barack Obama. But when I think of a president I don’t think of any president of the United States of America; I think about our local president of our local HBCU (historically Black college or university): President Dr. Kevin W. Cosby, Simmons College of Kentucky.

“What he and the Simmons family have done is unheard of in American history. They reacquired the college’s original campus, brought back course offerings, got reaccredited and became an HBCU. They took Kentucky’s first college for Black people and made it rise from ashes. This is reflective of the way the American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS) movement has rebirthed Black politics. ADOS has roots at Simmons, right here in Louisville. We hosted the inaugural conference, bringing thousands of Black Americans from across the country to our city. We unveiled the devastating reality of Black wealth. We put reparations on the Democratic presidential debate stage. We identified a new tribe of people who have largely been lost since the 1960s. We brought back the strategy of Martin Luther King Jr., the strength of Fannie Lou Hamer, the spirit of Malcolm X. And when you reflect on Dr. Cosby’s contributions through St. Stephen Baptist Church, he’s much more than a president of our HBCU, but really a president of Black Louisville. No one hires more Black people, educates more Black people, or supports more Black people.

“ADOS does not mean he doesn’t care or we don’t care for Black people around the world; it just means we acknowledge we need to take care of the ones here first — the ones who built the richest and most powerful country in the world but never got those riches or the power.”

.

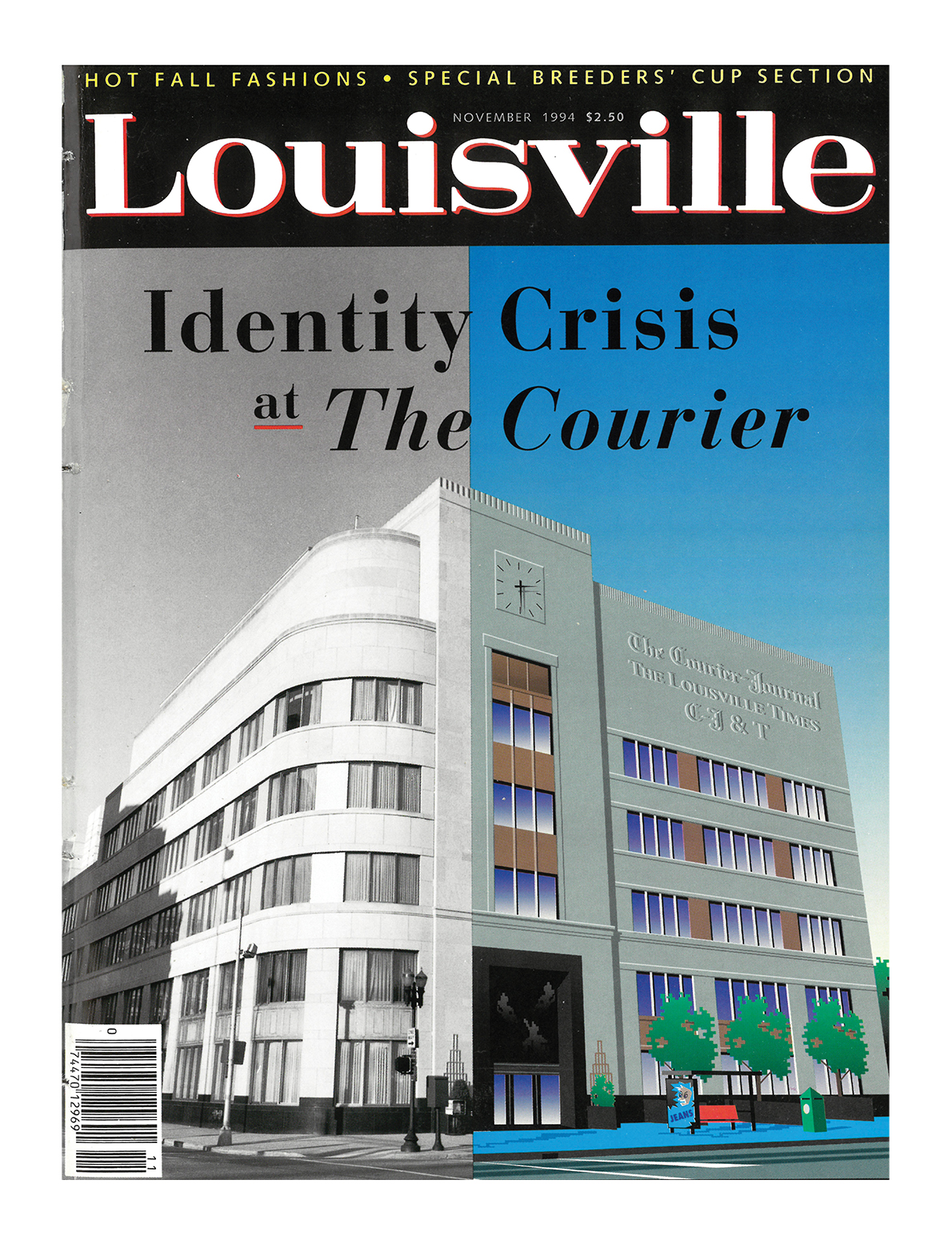

“I spent 27 years at the Courier-Journal, and these days when I drive by Sixth and Broadway, it pains me to see mostly empty employee parking lots. (A week after submitting these words, the C-J announced the building was up for sale.) I ride across Sixth Street, glance to the left, and see the empty loading dock where the newspaper’s green-and-white trucks once lined up to receive their allotted bundles for delivery to all 120 Kentucky counties.

“While I’m not sure which ‘identity crisis’ this Louisville Magazine cover was referencing, what I do know is that, in 1994, the C-J crew was hard at work. I recall being excited to join the staff of one of the nation’s 10 best newspapers with bureaus in Washington, D.C., Southern Indiana, Frankfort and across Kentucky. I am reminded of the Pulitzer Prizes won, and how, when I arrived from New York in ’84, the C-J and its now-defunct afternoon sister, the Louisville Times, combined to boast one of the most racially diverse local news staffs in the nation. We occupied a single newsroom split down the middle, but the C-J&T were fierce competitors. Ten years removed and I’m still proud to have served on an editorial board that took progressive, and sometimes even radical, stances on civil rights and social justice issues in this conservative state.

“The C-J, it’s fair to say, has an identity crisis several years running, transitioning from a largely print publication to a digital one. Top leadership is a revolving door. The news staff is lean, and more than 100 local jobs disappeared recently when Gannett shut down the C-J’s $85-million printing press and production operation and transferred those functions out of state.

“So now, in 2021, that magnificent Art Deco building at Sixth and Broadway is literally a ghost ship, largely empty, dark and filled with memories. But to echo two lines from one of my favorite songs: ‘Everything must change. Nothing and no one stays the same.’”

.

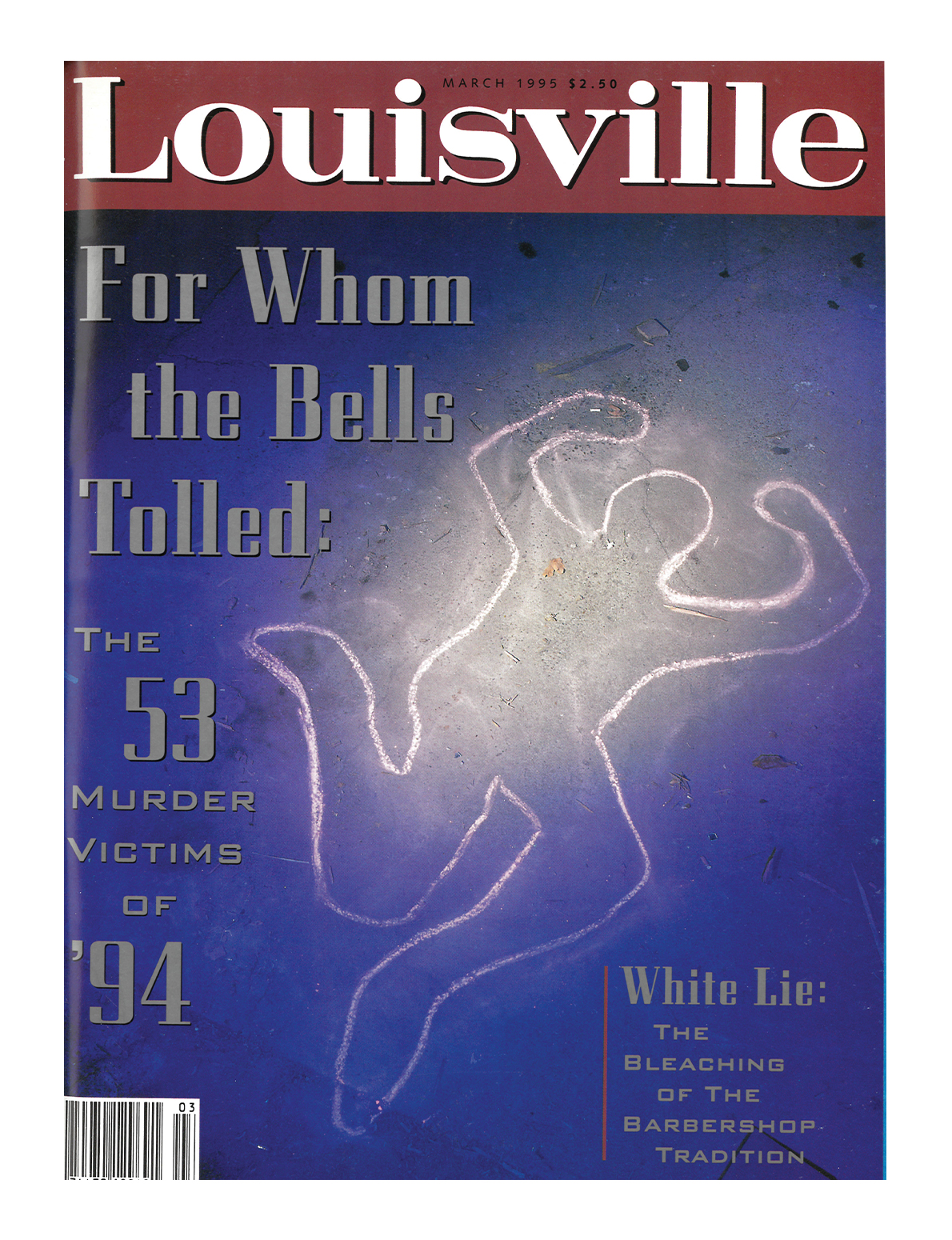

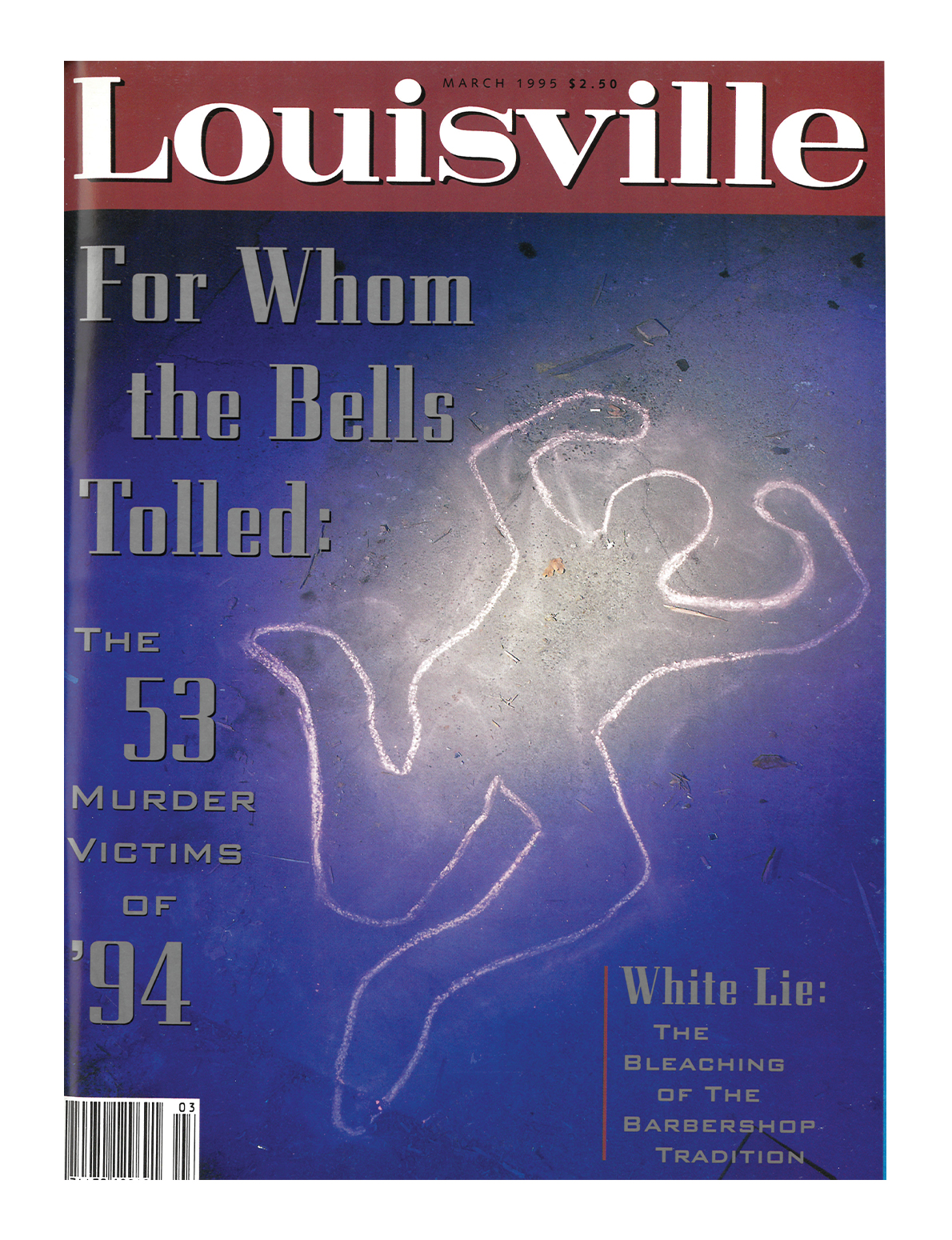

“When I see this old cover, it was March 1995. I was born in ’95. I’m seeing this chalk outline and the cover mentions ‘the 53 murder victims of ’94.’ Really, I’m fighting for a cause that has been going on way longer than my life, especially in Louisville. I’m just thinking about how things have not changed, yet we are still fighting for that change. The murder numbers have drastically changed. There’s more murders now, I’m sad to say. It’s really disturbing and disheartening.” (2020 saw more than 170 criminal homicide victims, the most ever for a year in Louisville. By the end of March 2021, the city was on pace to break that record. — Ed.)

“When you see a chalk outline like this, you know exactly what it is, and it just brings about so many different thoughts, so many different emotions. It’s so funny because I did a show called God Rest America in 2019 at Sheherazade on South Third Street, and one of the focal points was a chalk outline, on the floor right in front of the altar I created. A chalk outline really humanizes the tragic event of someone being murdered or killed. It can be terrifying. It can be traumatic.

“What my work has taught me over the last four years I’ve been sharing it with the public is that the power of art is real. You can really teach people to be empathetic of other people’s lives. I was very skeptical of considering my art healing work, but I’ve learned that my art is healing.”

.

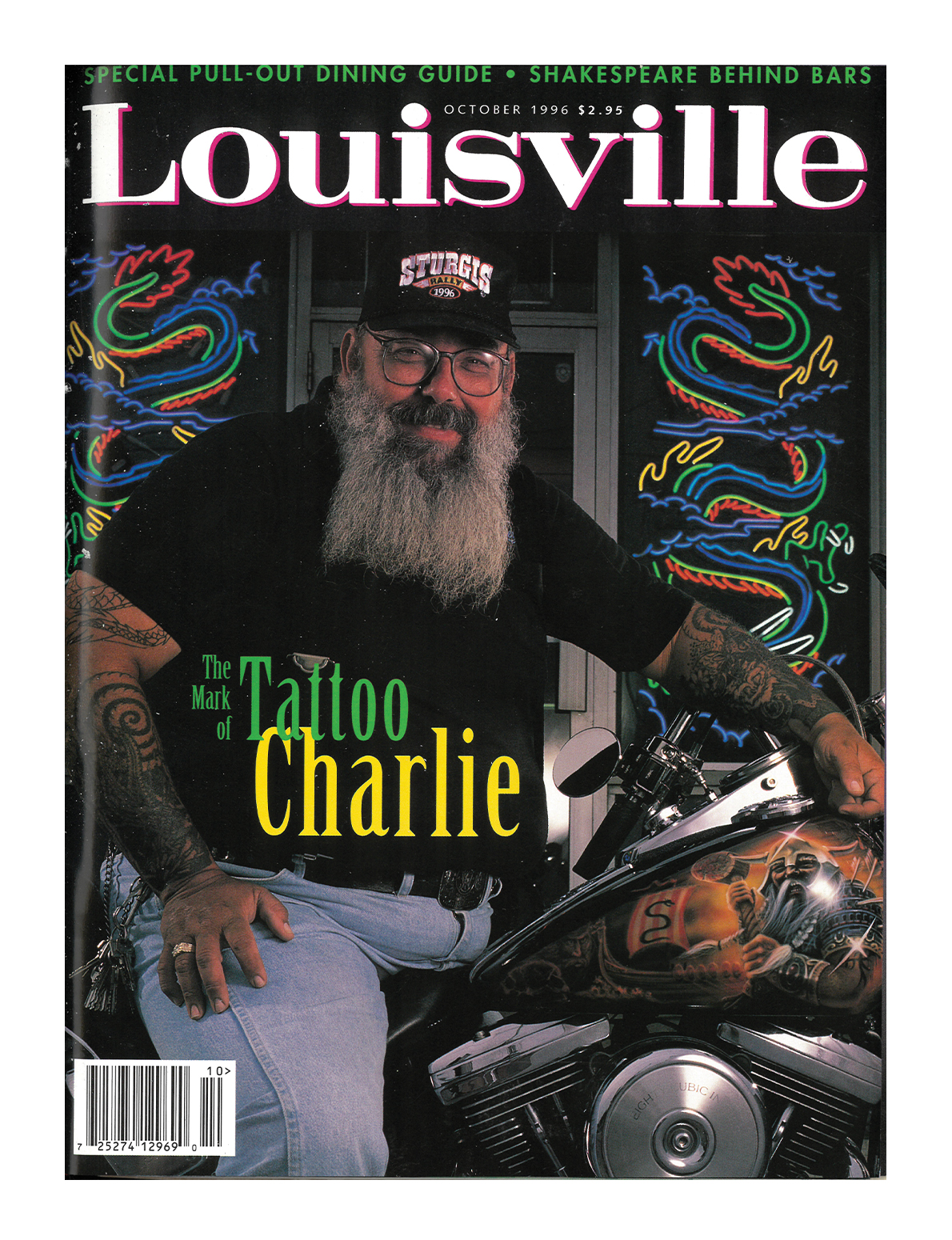

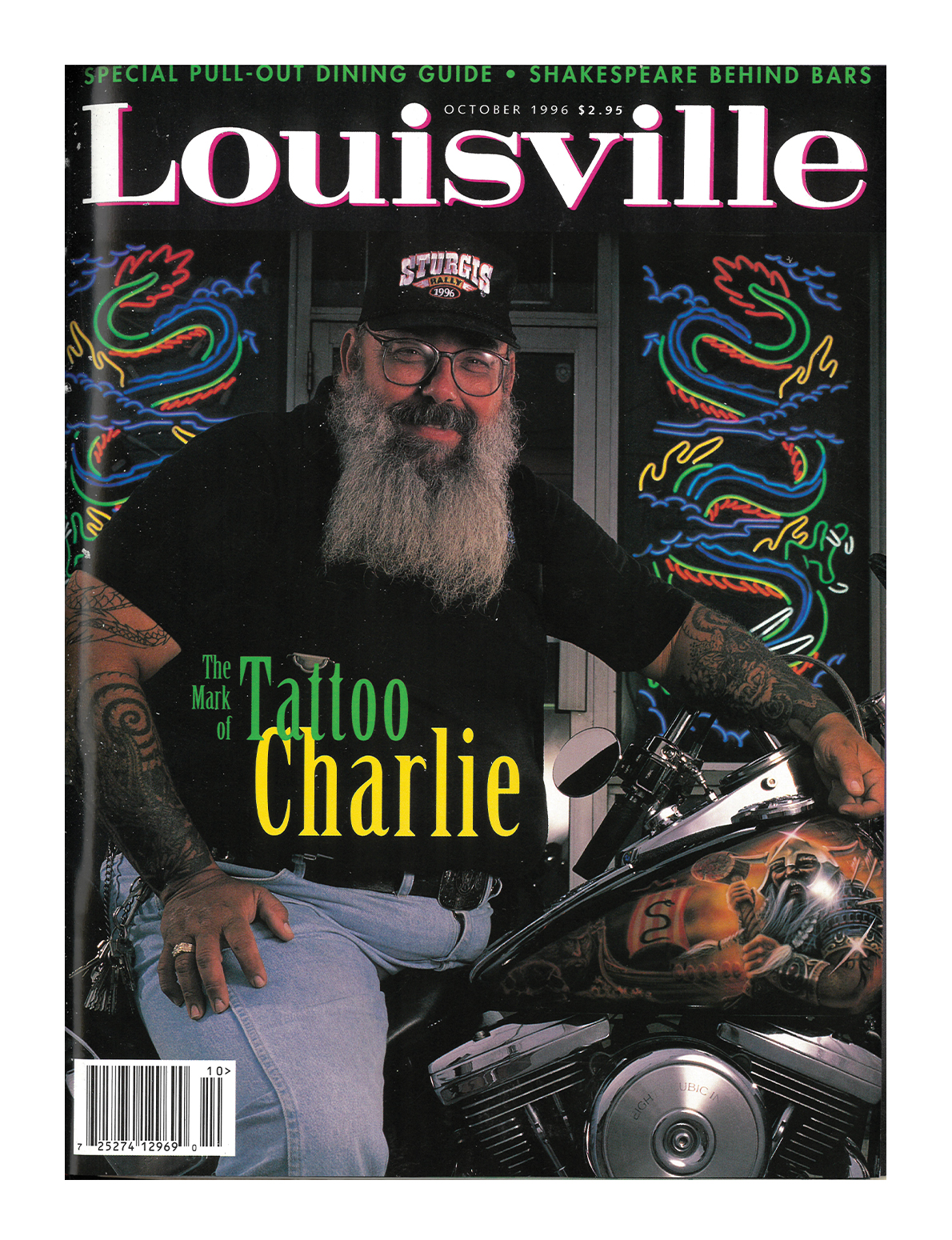

“Tattoo Charlie” — Charlie Wheeler, who died in 2007 — “brought so much to our industry. He helped shape this job into a more professional one. His shop (originally on Berry Boulevard in the mid-1970s, then with Preston Highway, Dixie Highway and Lexington locations) was one of the first to actually employ artists, where taxes were taken out for them and they collected a weekly paycheck. He streamlined the tattooing process and the dynamic between client and artist to make walk-in shops operate on a faster, more efficient level.

“Things have drastically changed in the last 20 years, though. Now the tattoo industry is dominated by appointment-only custom shops with artists who specialize in specific styles. Women tattooers are booming. We were once so scarce. The last convention I attended, there were just as many women tattooers. The industry has changed quite a bit, and I would say for the better, although we still respect and appreciate all that our elders brought to the industry and made possible for us through their struggles. None of us would be here today without them.”

.

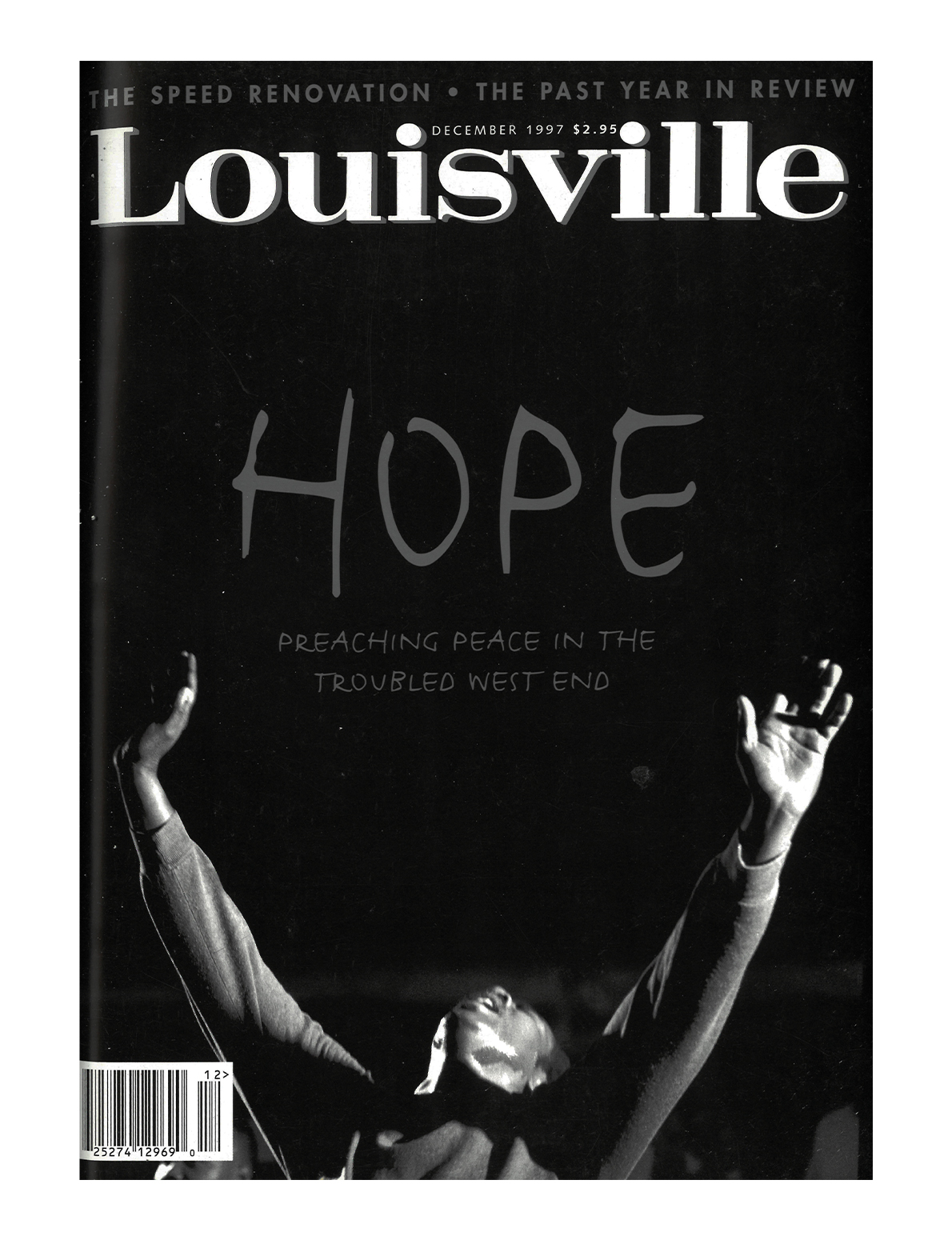

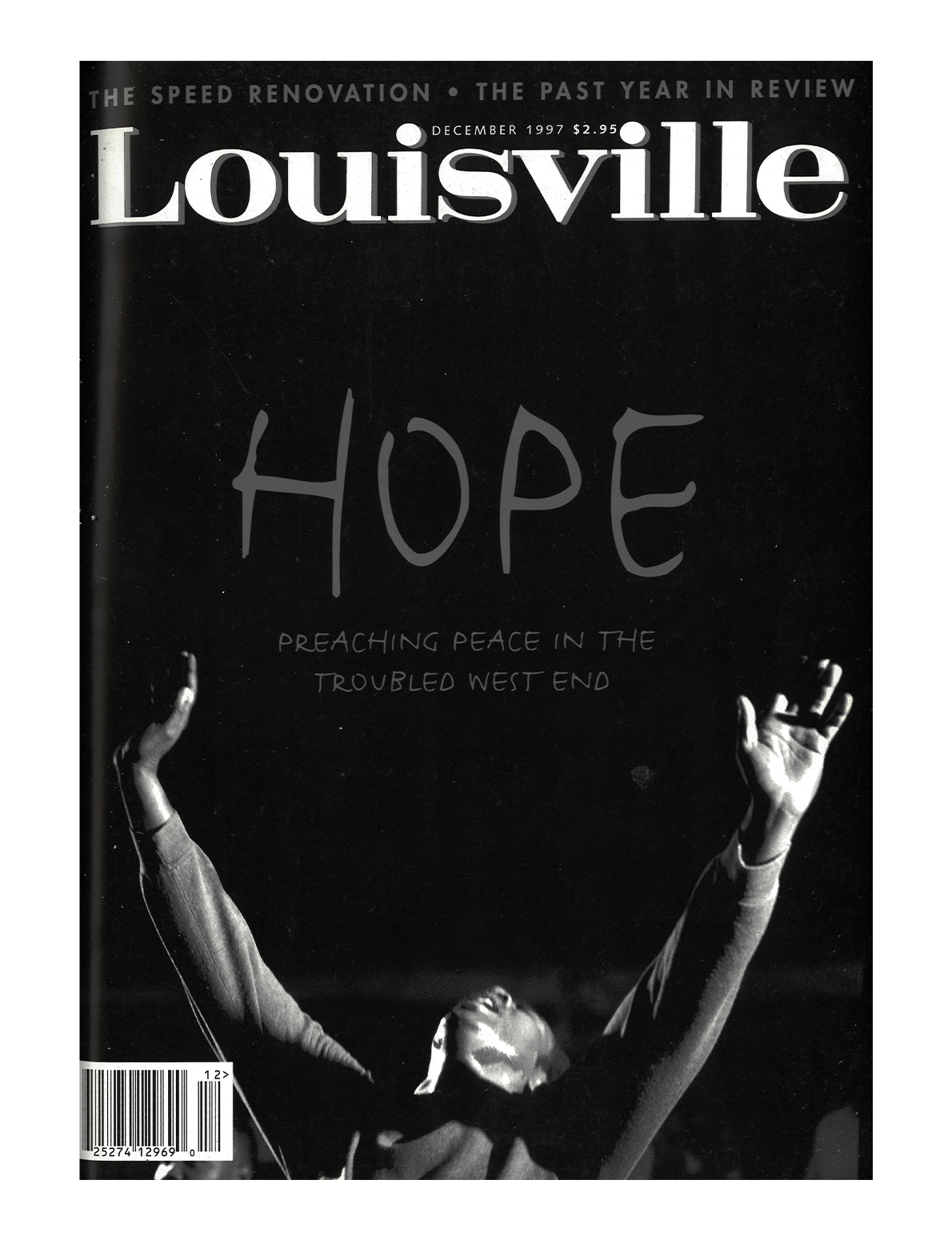

“One of the biggest challenges we face as a city is our inability — corporately, civically and as policy leaders — to understand how limited the available choices are within communities that have been economically excluded for hundreds of years. So I was struck by this concept of how ‘hope’ and ‘preaching peace’ is somehow the remedy to assure peace in the West End, as though the experiences of West End residents are attributable to their absence of hope or their desire for peace. The contrary is true. Black people, in every community, have wanted nothing more than an anchoring to hope, economic vibrancy, inclusion in the ever-elusive American dream, peace and safety in the community, and a country that is our home. Yet all of those concepts have been thwarted by current and lingering inequitable policies, choices and behaviors outside the Black community. My reaction to this cover is that it is dripping with presumptive privilege and arrogance, is misguided and dilutes the culpability that we all have in passively and actively reinforcing exclusion based on race. I am fairly confident that this cover, expressing this kind of sentiment, phrased in this way, would not fly in today’s environment as a cover for Louisville Magazine, and for that I am thankful.”

.

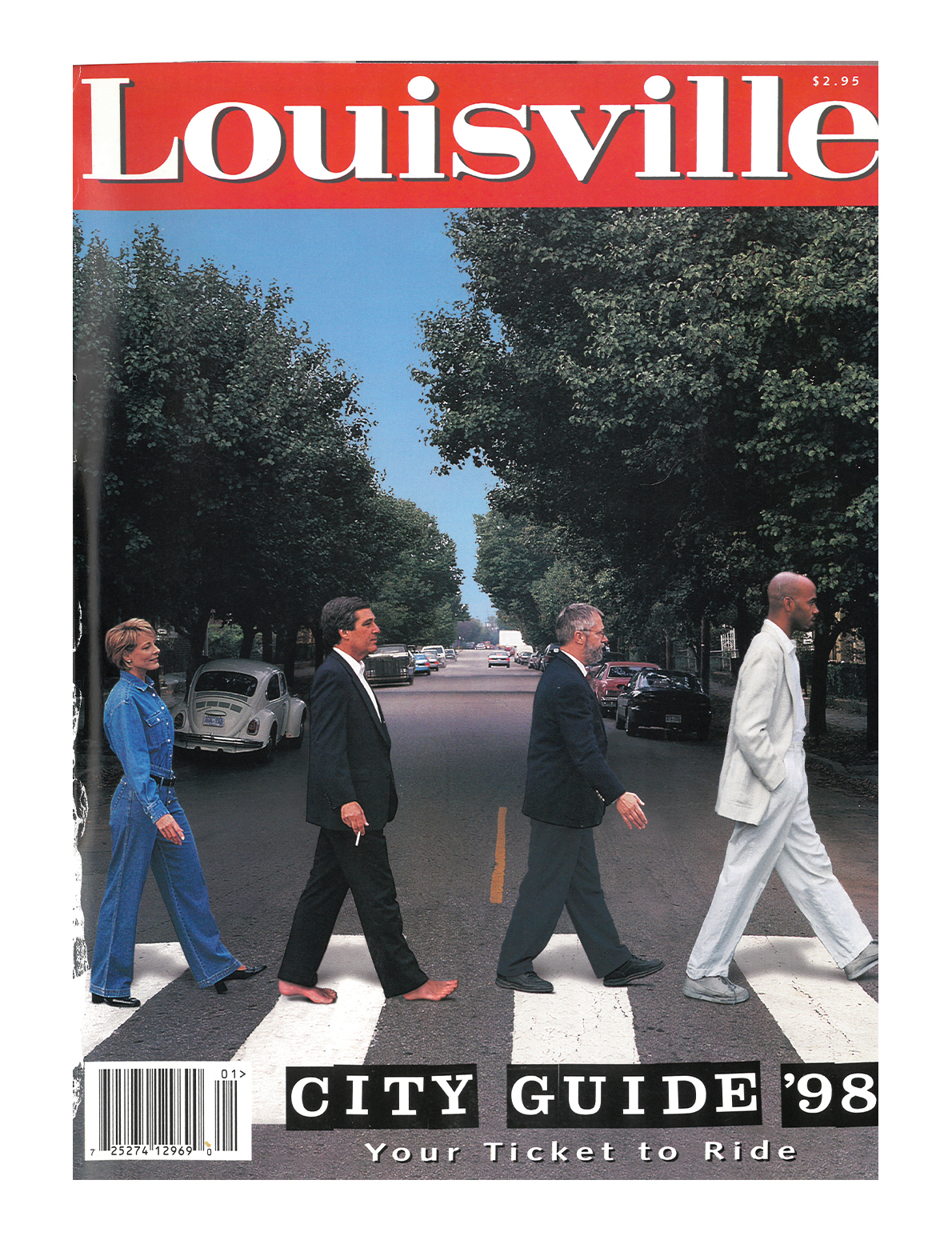

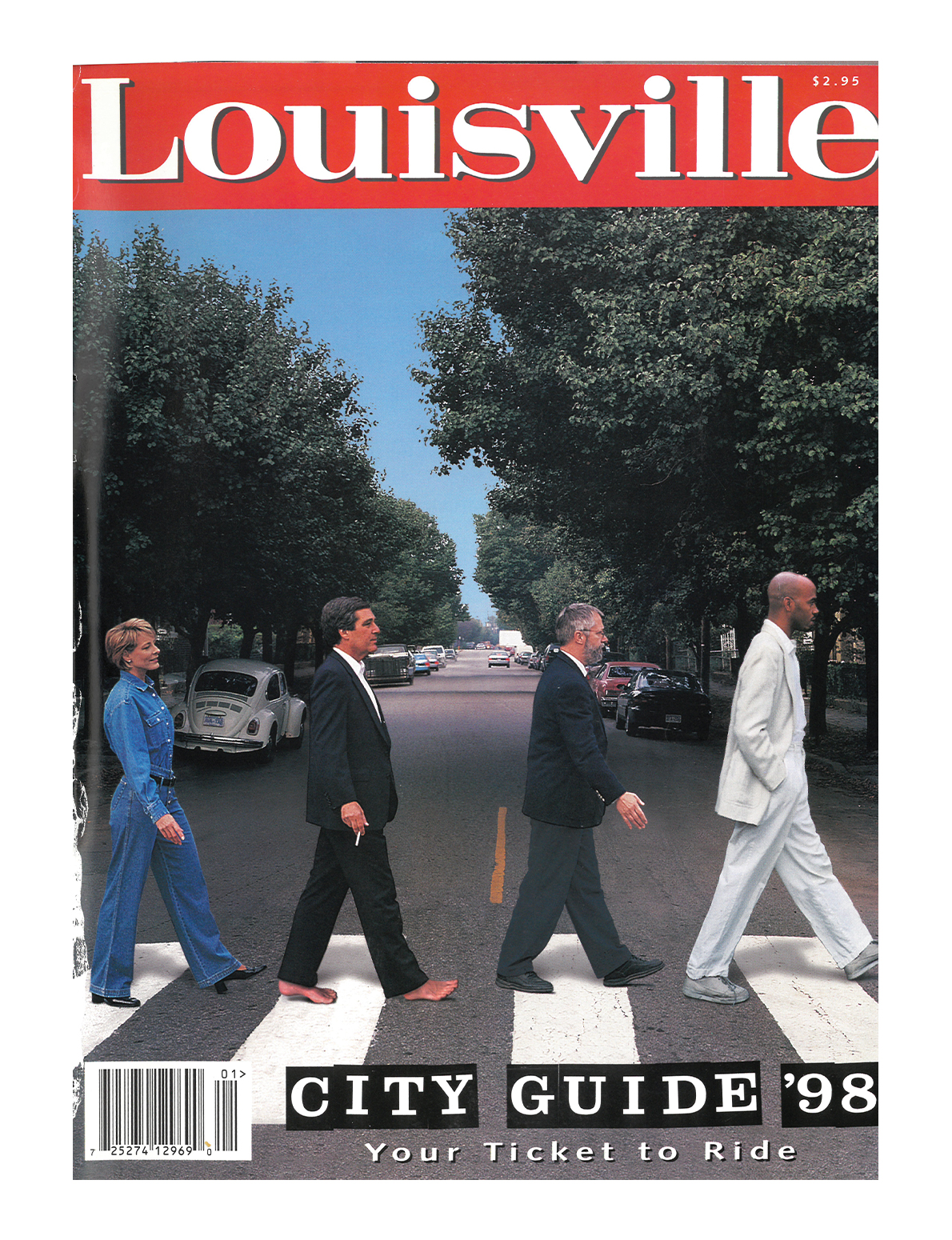

On the Abbey Road-inspired cover: WAVE-3 anchor Jackie Hayes (since retired), then-Mayor Jerry Abramson, Jon Jory of Actors Theatre (since retired), former U of L hoops star Darrell Griffith.

“My picks for today’s Abbey Road cover: Sadiqa Reynolds, president and CEO of the Louisville Urban League (Sadiqa for mayor!); Jeff Walz, U of L’s women’s basketball coach; U of L president Neeli Bendapudi; and Dawne Gee, WAVE-3’s best news anchor and a beloved local celebrity. And if I could add a fifth Beatle it would be Stephen George, president of Louisville Public Media, who’s carrying the torch to keep local journalism alive and well in the midst of corporate takeovers and dangerous misinformation.”

.

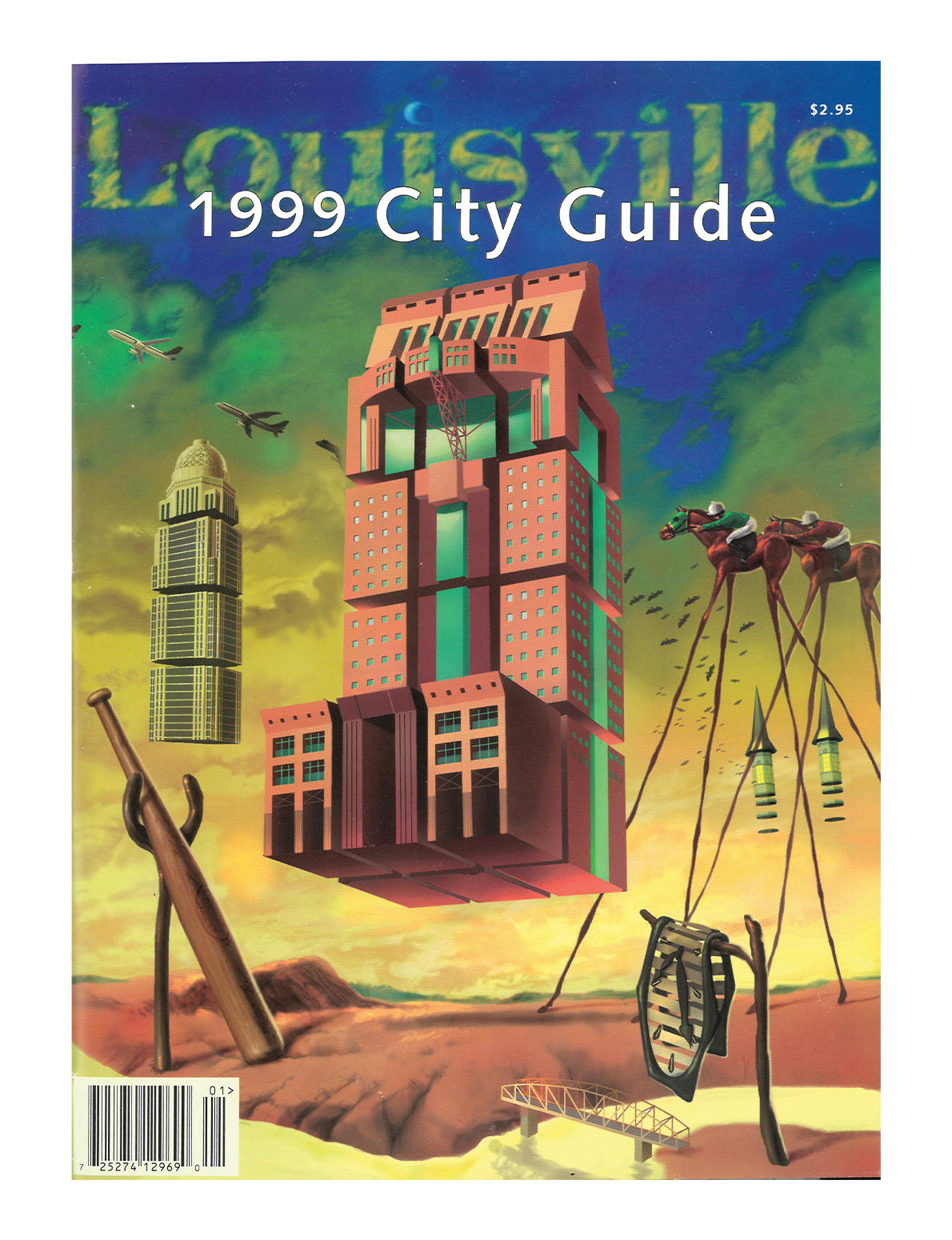

“If only Dalí were from Louisville. A guy can dream, right?

“On the cover, I love the reference to the infamous surrealist painter and subtle nods to retro sci-fi pulp covers — very appropriate for the new millennium. As an artist, this makes me want to see a series of Louisville-specific scenes rendered in the style of notable painters. Imagine a scenic landscape of Waterfront Park as a Monet; a Derby-inspired Pollock; the recovered oddities and treasures of the Falls of the Ohio immortalized as a René Magritte!”

.

“She ought to be on a building, btw.”

.

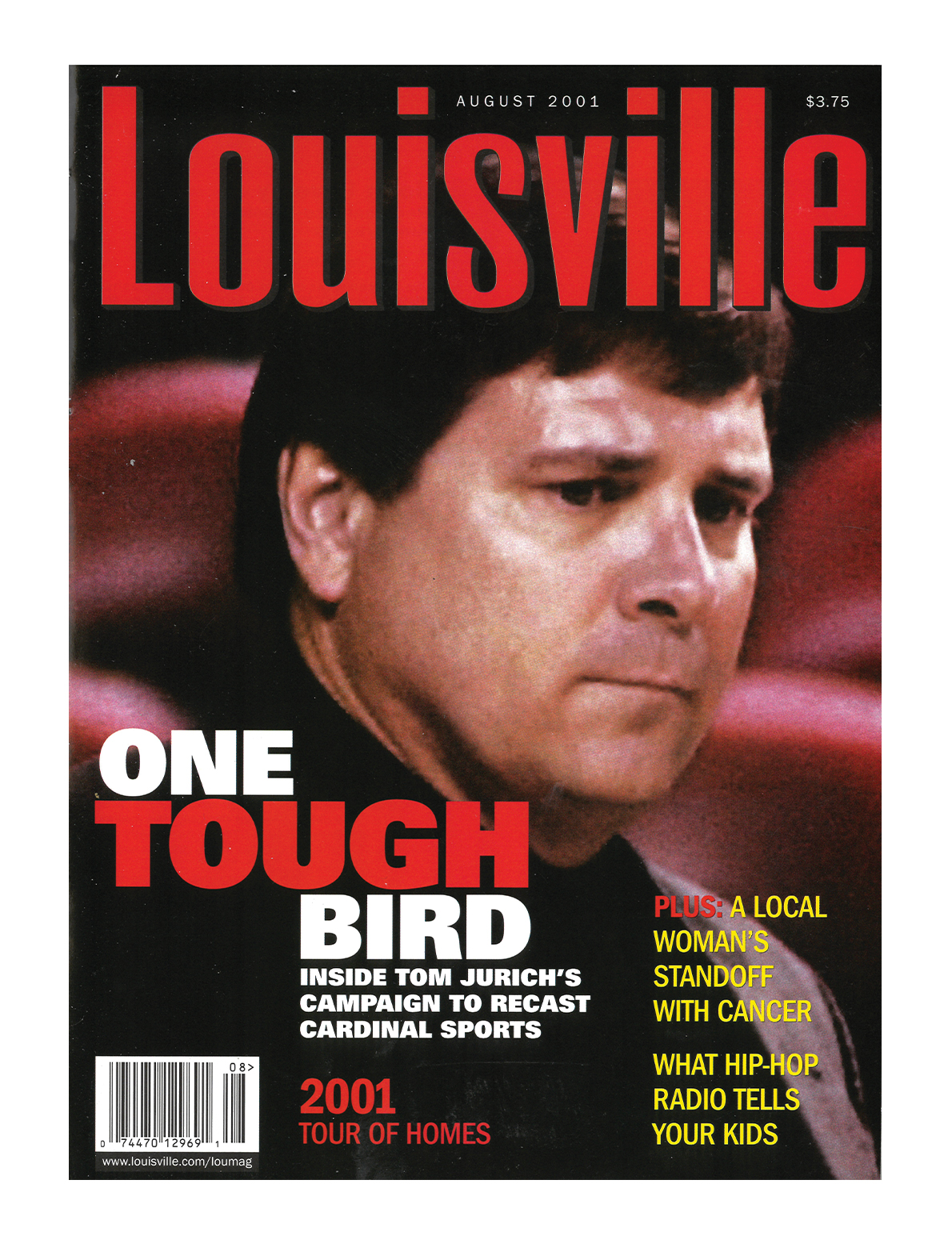

“Determination. That’s what I see when I see this cover. U of L athletic director Tom Jurich wasn’t determined just to rebuild a men’s basketball program or a football program consistently ranked in the top 25. He was determined to build a complete and competitive athletics department. When I moved to Louisville in fall 2011, success had already arrived for Jurich and Louisville. He always struck me as someone who really enjoyed the success, but it was about keeping all the programs at the top. Making sure people believed Louisville was not a stop on the journey but a destination. This is a cover of someone who hadn’t arrived yet, even though he’d just hired Rick Pitino a few months prior.

“In his final days at U of L, Jurich had already dealt with several scandals and controversial issues with his programs and coaches. I did get the sense he thought he was above authority. That he was untouchable. It’s probably why it came as such a shock to so many people when Louisville fired him.”

.

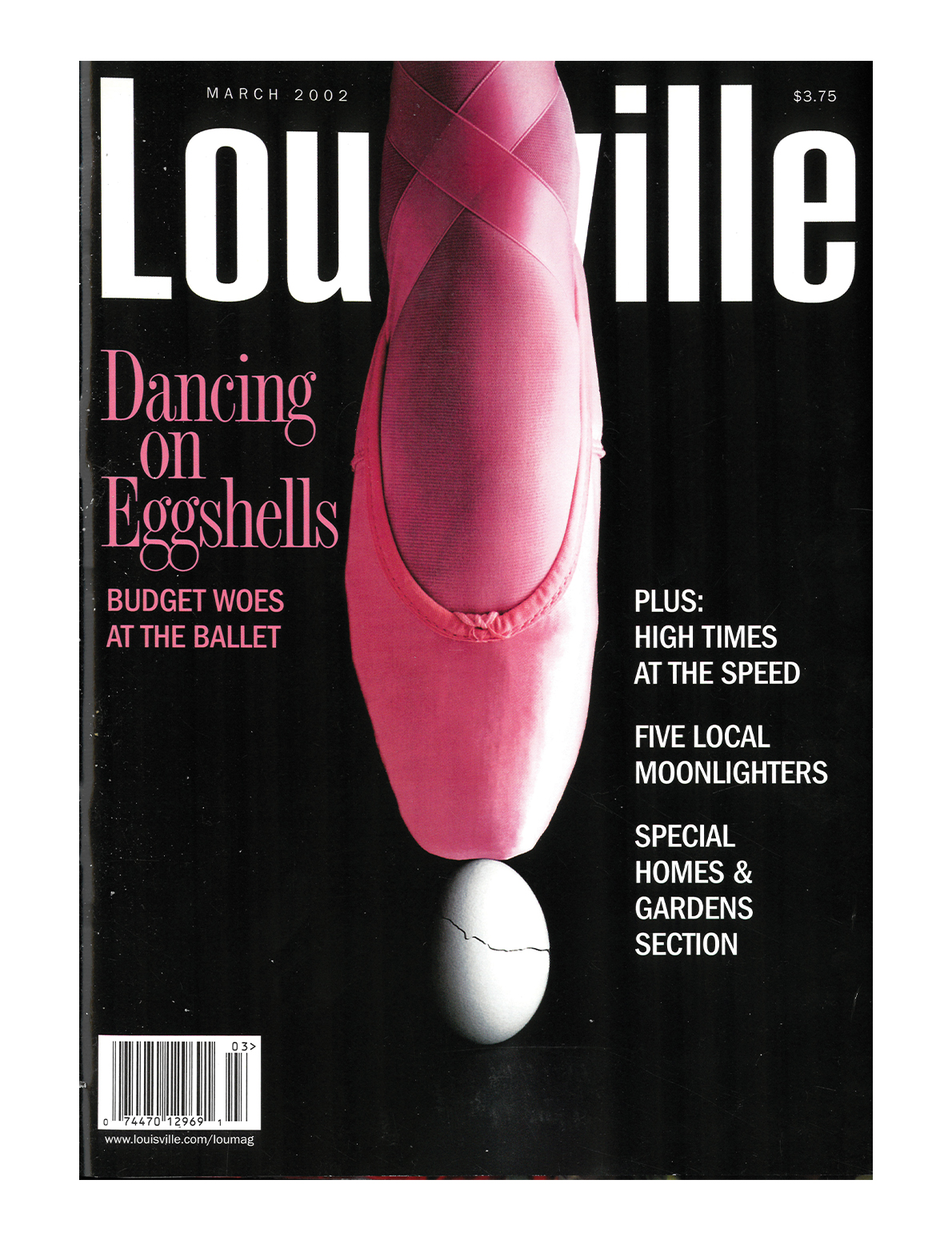

“When I start by just looking at the image, I’m reminded of its origin story — the famous ‘Toe on Egg’ poster by (the late) Louisville-based graphic designer Julius Friedman. Julius was definitely a legend, and this poster ended up with a life of its own, showing up in the background of films and collected by people all over the world. He probably could’ve picked up and moved anywhere and been successful, but I appreciate that he made the choice to stay here, in the town where he was born — that he saw the artistic promise and vibrancy here.

“Of course, I also can’t help but see the precariousness of this cover image, even in the original design (which had an uncracked egg). I imagine the dancer connected to that foot, inside that pointe shoe — the strength of that impossible, improbable dancer lifting herself up enough to balance. To keep the egg from shattering.

“Ballet can seem precarious — as a career, as an art form, as an institution. But to be a ballet artist requires incredible strength. And to survive as a ballet company, especially to be almost 70 years old like Louisville Ballet will be next season, requires so much tenacity, vision, and commitment, both from the company and from the community that supports it.

“Julius was definitely on to something, in his original poster design and in his love for the artistic community of this city. I may not be a lifelong resident, but I understand why he stayed. This year has been tough, and I would be lying if I didn’t admit it. But I’ve felt so lifted up and supported by this community — both inside and outside our studio walls. I’m left feeling like Louisville Ballet, with this support, is anything but fragile.”

.

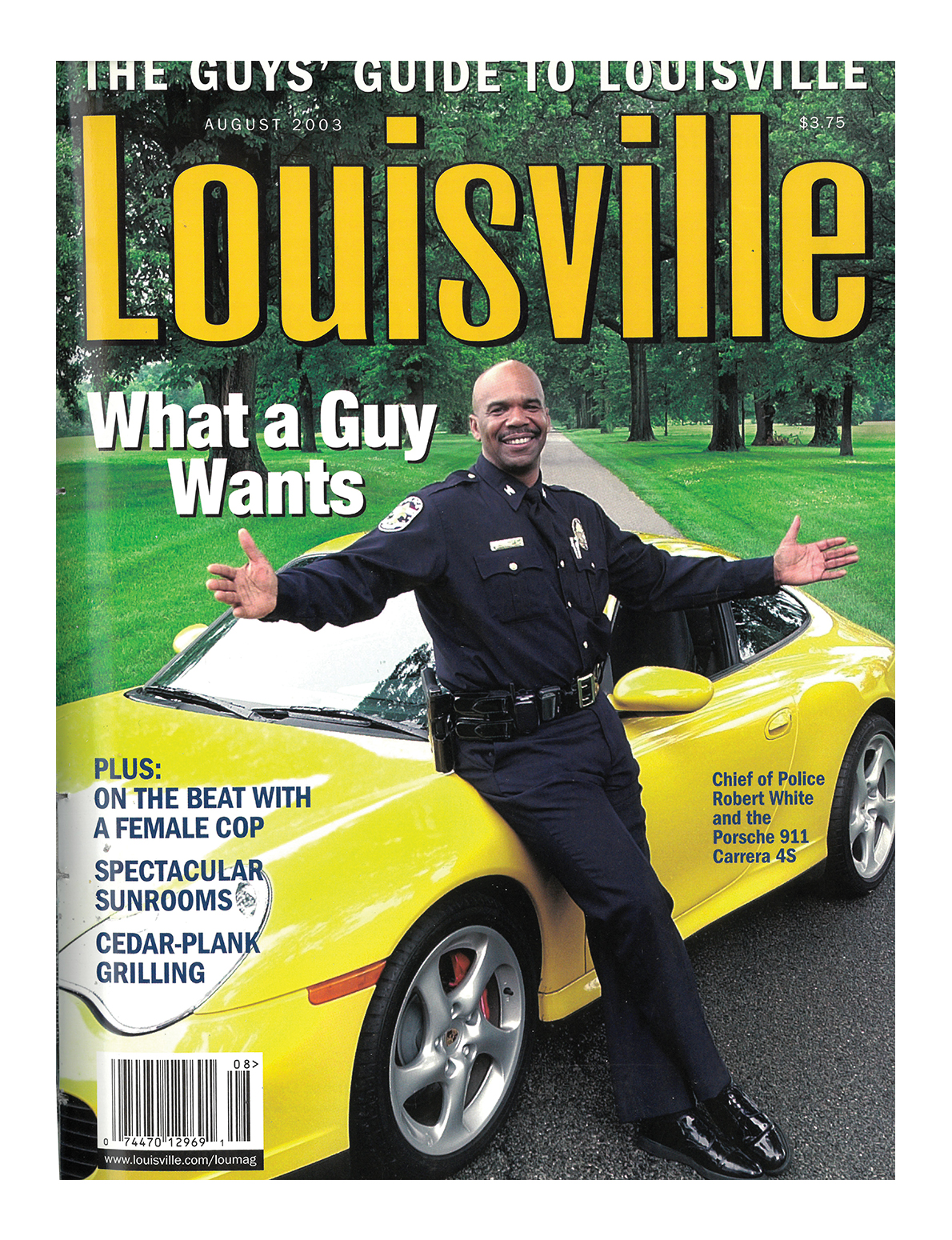

“Seventeen years before Breonna Taylor was killed by Louisville police during a no-knock-warrant raid of her private residence in the middle of the night, Louisville cops and nice cars made the cover of magazines. What went wrong?”

.

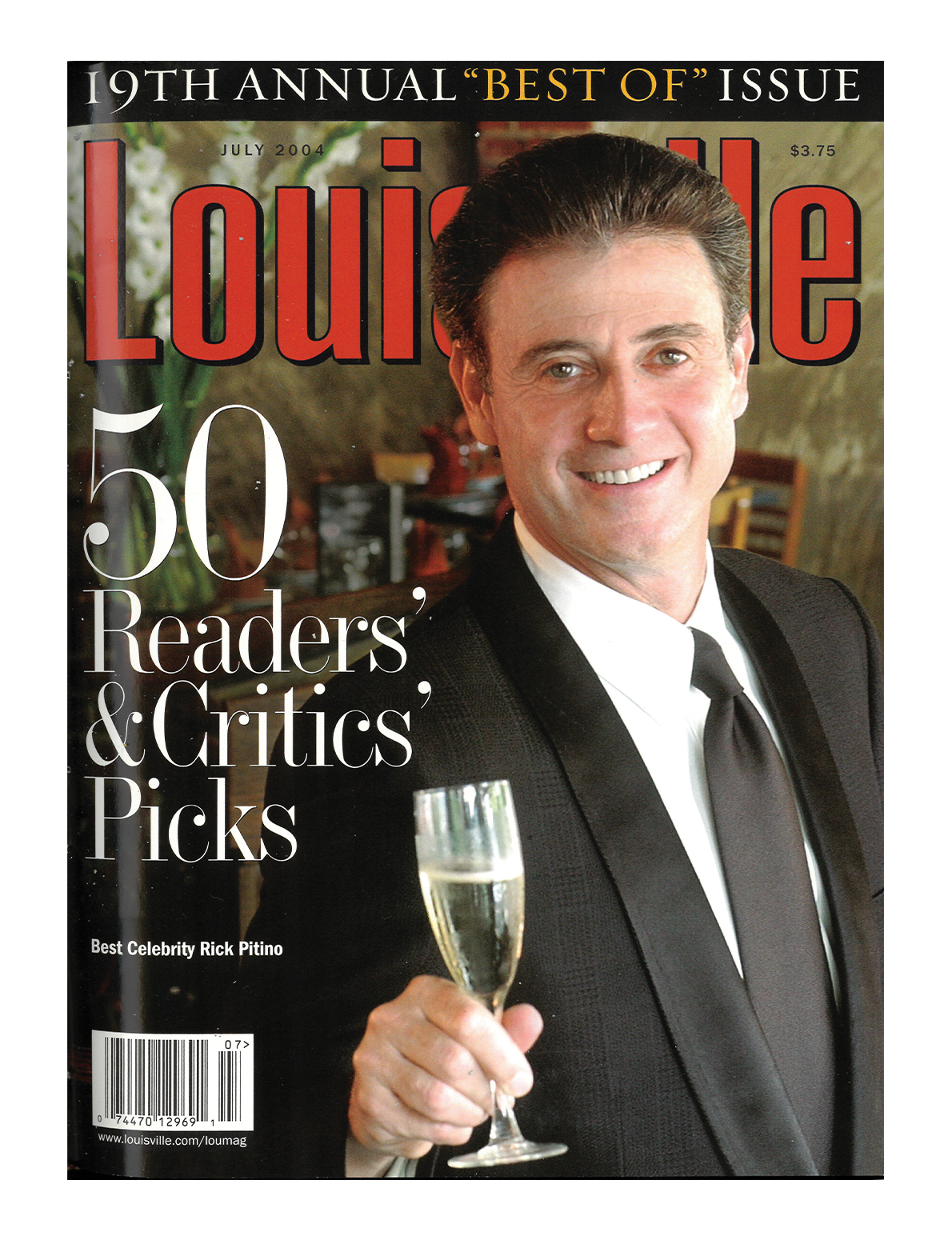

Cover caption from the table of contents (no joke): “Best Local Celebrity Rick Pitino at Porcini, the Best People-Watching Restaurant.”

“Well…that is — that is certainly a caption. Best People Watching, eh? I want to make one of three dozen low-hanging jokes, but the evidence that this is all a simulation and whoever’s running the show is getting bored with us has never been stronger. I’m honestly terrified right now. Best People Watching? There’s no way this is real. No way. It’s too perfect.”

.

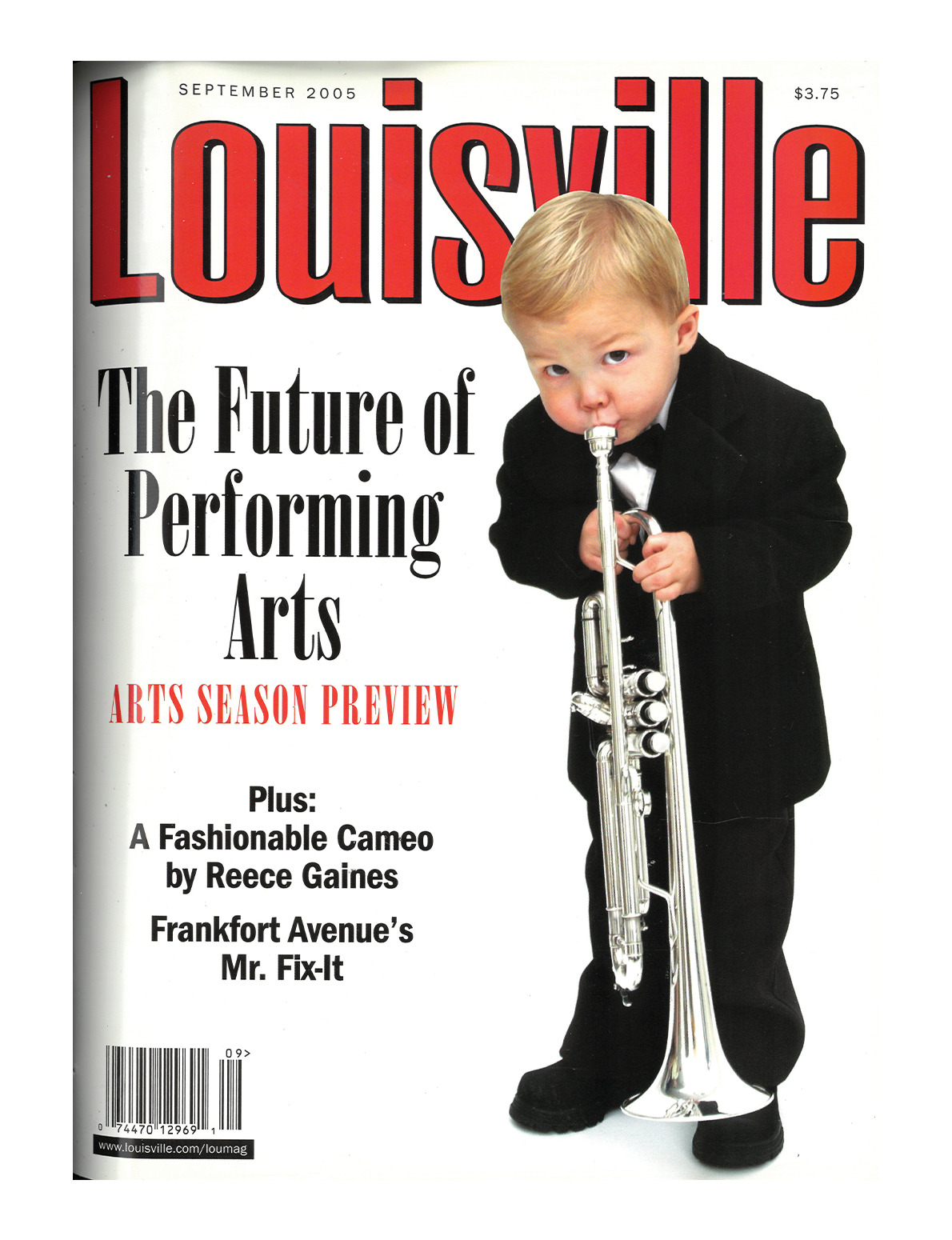

“I don’t remember the day of this photo shoot because I was three years old at the time. We have many copies of that magazine in our house; it’s a great conversation starter. I was holding my dad’s trumpet. He played it all through high school and college and up until last year, when he bought a new one.

“I grew up in a very musical family, my mom being a band director and my dad playing trumpet. I always knew that, once fifth grade began, I was going to be in band. I went to Crosby Middle School, and my director was Joseph Stivers, who pushed me to practice my trumpet a lot. I started making all-district band and getting distinguished ratings at solo festivals. He truly was an amazing teacher and friend. Once I got to high school, my parents put me in private lessons with Ryan McCaslin. Throughout my time at Eastern High School, I was part of All-State three out of the four years, including first chair this year, Governor’s School of the Arts, Louisville Youth Orchestra, All-District Band and more. Looking ahead to college, I am going to major in music education. I aspire to be in a position to impact students the way my teachers impacted me.”

.

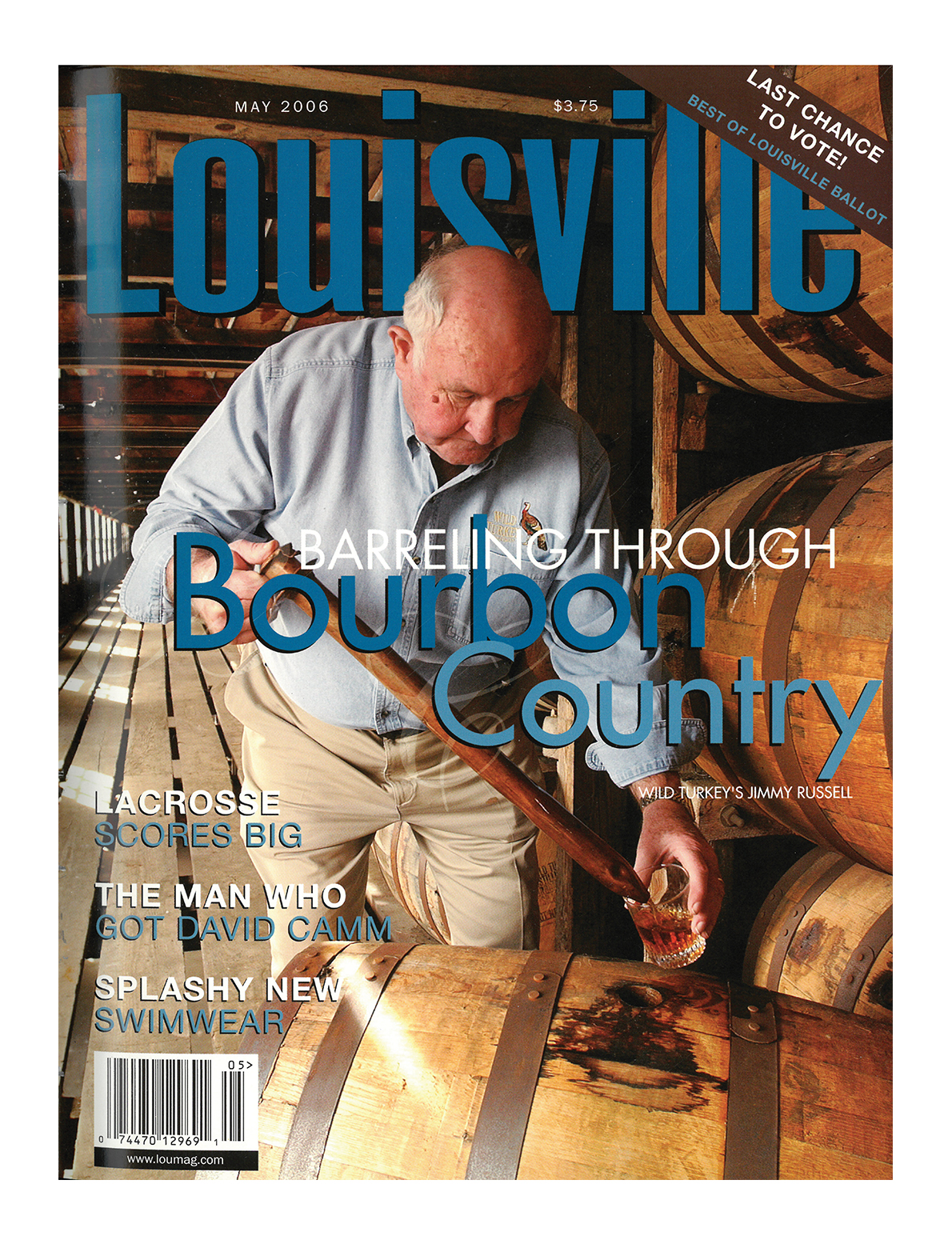

“This cover really only needs two of those words: Jimmy Russell. The Wild Turkey master distiller is bourbon.”

.

“When I think of the title ‘How Green Are We?,’ I can’t help but think of our current pandemic and how we are all impacted by actions that happen far away. The transmission of zoonotic diseases is a result of degradation of the environment, and Covid-19 is no different. When we ask ourselves how green we are, we are taking responsibility for our actions as a community, but also across the planet.”

“I remember that issue and pulled my copy from my files to reflect on it more clearly.

“Environmental scorecards are always a mixed bag. The discussions that go into them are much more informative than any grades we assign. Comparing 2021 with 2007, I’ll offer the following thoughts:

“1. More of us are acting on the dire need for climate action. More young people see the connections to racial justice. We’re investing more into energy efficiency and solar power. We’ve seen big reductions in our four worst sources of air pollution, especially air toxics. Storms are more intense, but they send less sewage into Beargrass Creek and the Ohio River.

“2. But we continue to worsen our dependence on automobiles by building more suburban sprawl while giving sidewalks, TARC or bike routes short shrift. Lacking a car still means second-class citizenship here. We continue to lose trees, especially by suburban developers, faster than we replace them, though we have more public and nonprofit programs planting trees.

“3. I continue to lament our lack of progress on diversifying our local environmental movement.”

.

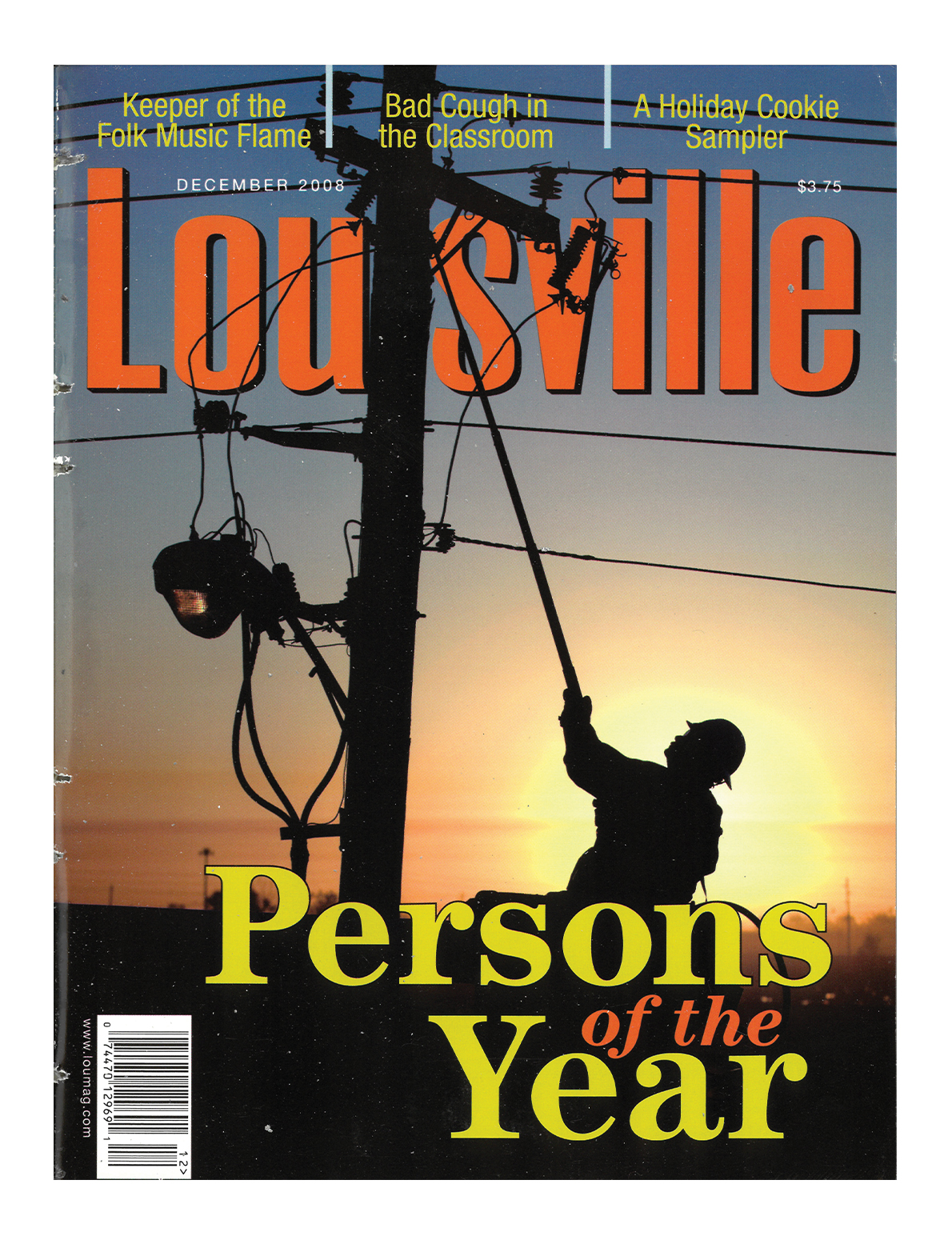

“In September 2008, Hurricane Ike blasted through our area, creating one of the most memorable windstorms we have seen. I vividly remember when the sun broke out that afternoon and knowing we had a serious problem. That sun allowed the strong winds aloft to blast to the ground, and we ended up with 75 mph winds in Louisville. In the metro area, 300,000 lost power, and little did we know that, four months later, the monster ice storm of 2009 was coming. The utility workers had two monumental tasks to handle in only four months. I can’t even begin to fathom the endless task they faced.”

.

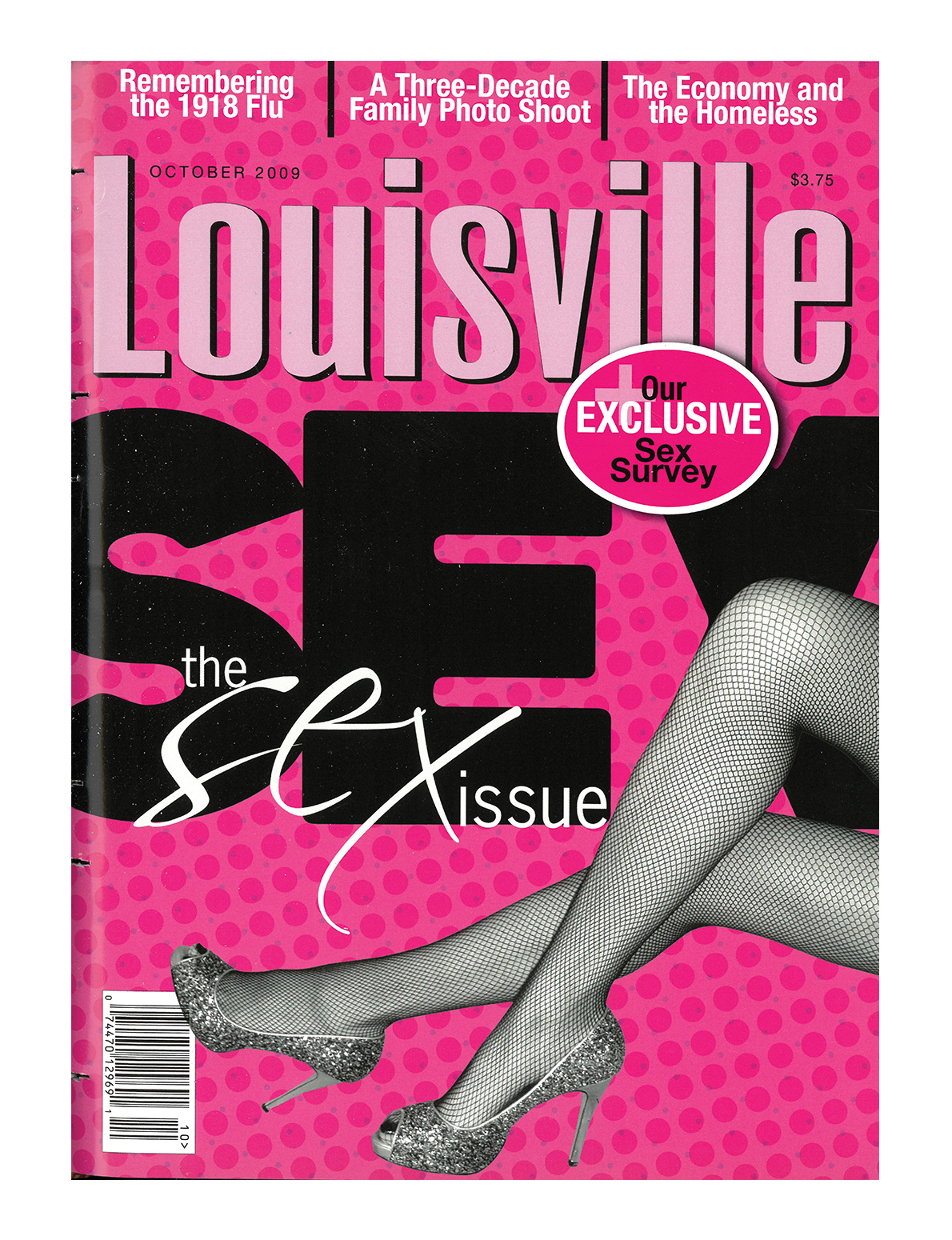

“This cover made me laugh and brought up so many questions about what was in the actual issue. When I first looked at this cover, my initial reaction was that I love the pumps and the fishnets, but I also asked: Why use the colors pink and black? Was this to make the issue seem more provocative? Is sex in the issue discussed in a salacious way or an informative and practical way? My eyes then went to the image and copy: ‘Our Exclusive Sex Survey.’ This made me think about who was surveyed? Were the respondents diverse in terms of race, sexuality and/or gender identities?” (No: 550 respondents filled out an online survey — a collaboration between the magazine and Indiana University’s Center for Sexual Health and Promotion — answering questions like: Is it OK to have sex without being married? 89 percent of respondents identified as heterosexual. — Ed.) “Or was this just another white cis-het survey that replicated the limits of discussing sex and sexuality without diverse voices at the center? Did this issue discuss consent before, during and throughout the act of sex and what that looked like for readers? This cover made me think of how, even in 2009, sex was still seen as such a taboo issue and not one that needs to be discussed in informative, practical and nuanced ways.”

“If the editors missed the mark with this cover, they also missed an opportunity: to depict sex in an exciting, affirming light. But instead of coming across as suggestive, which appears to have been the goal, it comes across as vanilla and, worse, patriarchal, heteronormative and racist. I mean, who besides a heterosexual straight man would see an image like this and think “sex”? By exclusively catering to the straight white male gaze, this cover erases queer sexuality, perpetuates sexism (woman as sex object rather than subject or recipient of pleasure) and reinforces white supremacy (white woman as ideal sex object). If Louisville Magazine does another sex issue in the future, there are some amazing queer BIPOC artists and photographers in this city who could provide some amazing erotic imagery for the cover.”

.

“Wow. It’s funny to see a cover about how to enjoy ‘The Great Indoors’ and know it was only addressing a month or two worth of winter boredom. I would love to read this article and see how many of the ideas are things I’ve seen people do throughout the pandemic, while we were all ‘enjoying’ the great indoors for longer than we ever thought we would!”

Some of the suggestions from the 2010 package: rock-climbing at a big gym in the Bluegrass Industrial Park, hot yoga, “body-rejuvenating services” at Z Salon, blacksmithing classes in front of a blazing forge, watching swim meets inside the toasty natatorium on U of L’s campus. All of which would’ve been closed during lockdown. Writer Jenni Laidman knew what to do, though: “Comfort food is a can’t-miss medication. Chicken potpie, made with a cream sauce with a touch of sherry, is like therapy for the whole family, without the embarrassing show of emotions or need to open old wounds.”

Back to Ellis: “I actually bought a house on June 1, 2020 — I was a renter before — and I wouldn’t recommend moving while simultaneously covering a global pandemic and racial-justice uprisings. But it definitely kept me from getting bored during lockdown. I was a little envious of people picking up new instruments and languages. For me, my three little dogs, Wilson, Radar and Barkley, made my house feel like home. Radar reminds me to move, Barkley reminds me to rest and Wilson reminds me to clean the floor and not skip dessert. Wilson’s 16. She pees where she pees, and she eats gelato every night before bed.

“Now that we’re on the road to being vaccinated, I do look forward to having a delayed housewarming…and maybe I’ll ask people to bring samples of all those dishes they learned to make during Covid!”

.

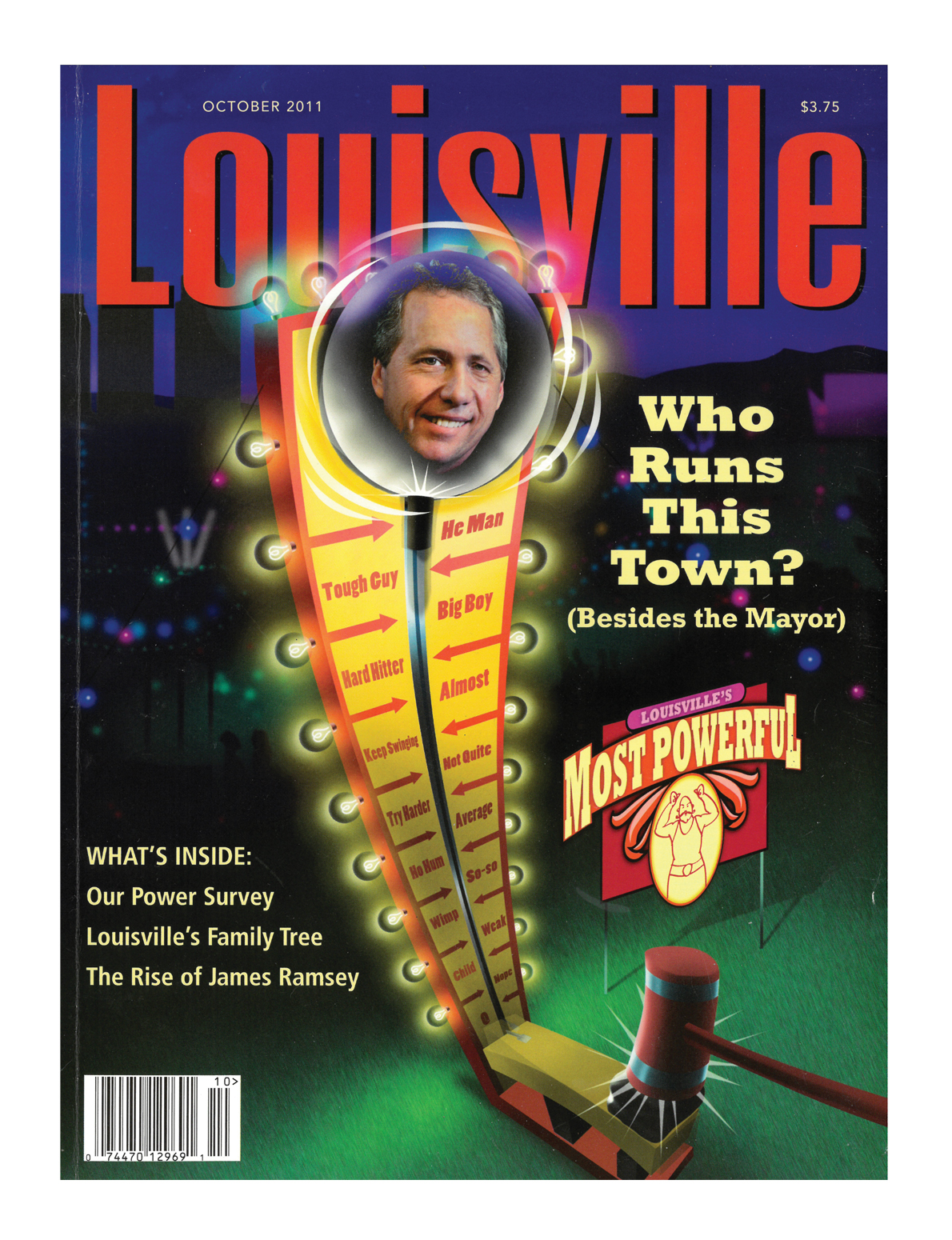

“A lot can change in a short period of time. Louisville will forever be defined as pre-Breonna Taylor and post-Breonna Taylor, and the future of our city hangs perilously in the balance. While the power brokers of Louisville cling to what was and has been, something new is being born. A new power is emerging in Louisville: the power of the people. Will the old guard see the power in their vice grip evaporate through their fingers? Will we see a wave of progressive leaders set a new agenda for our city? Who will run this town? It’s an open question.”

.

“Pretty fly for a white guy.”

.

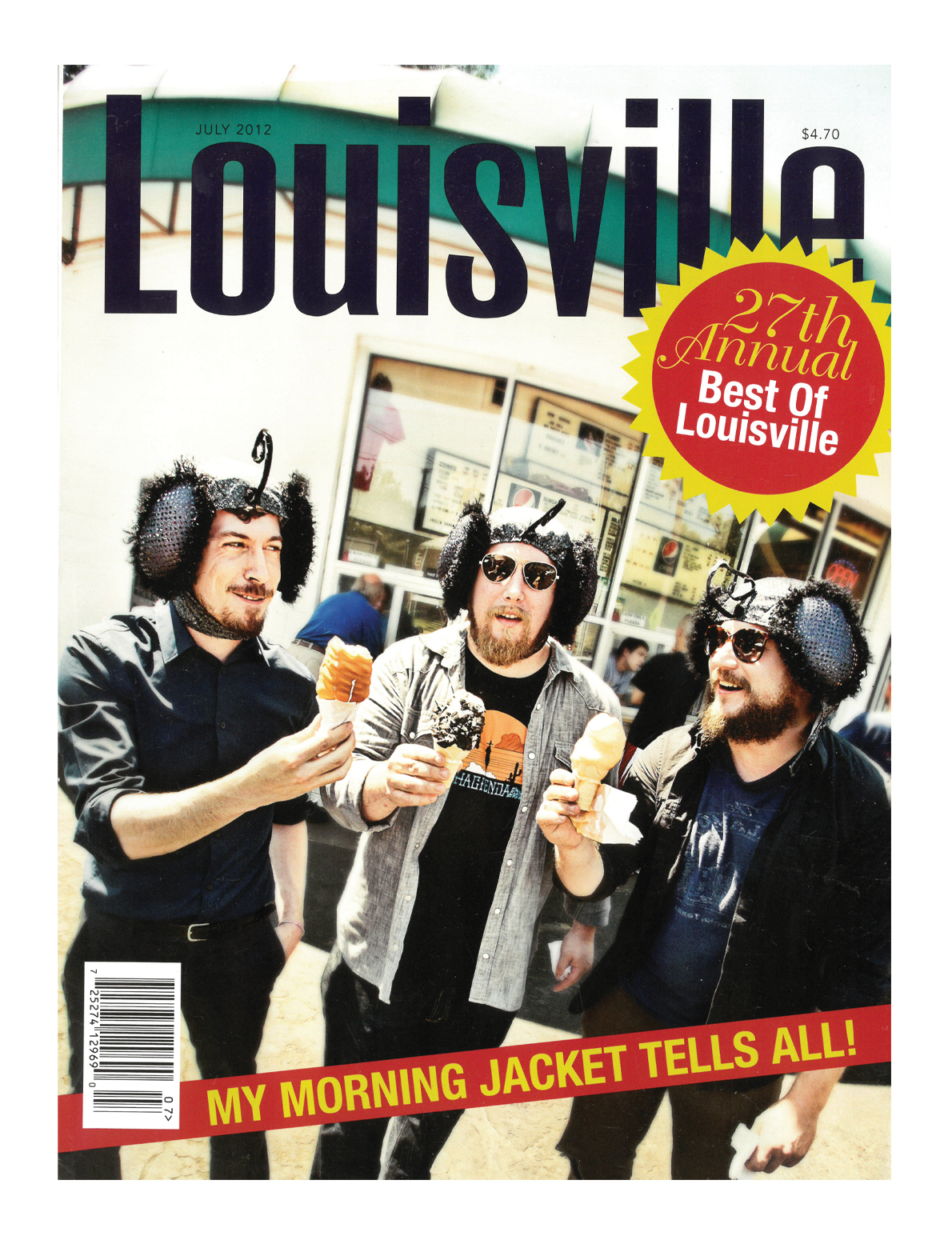

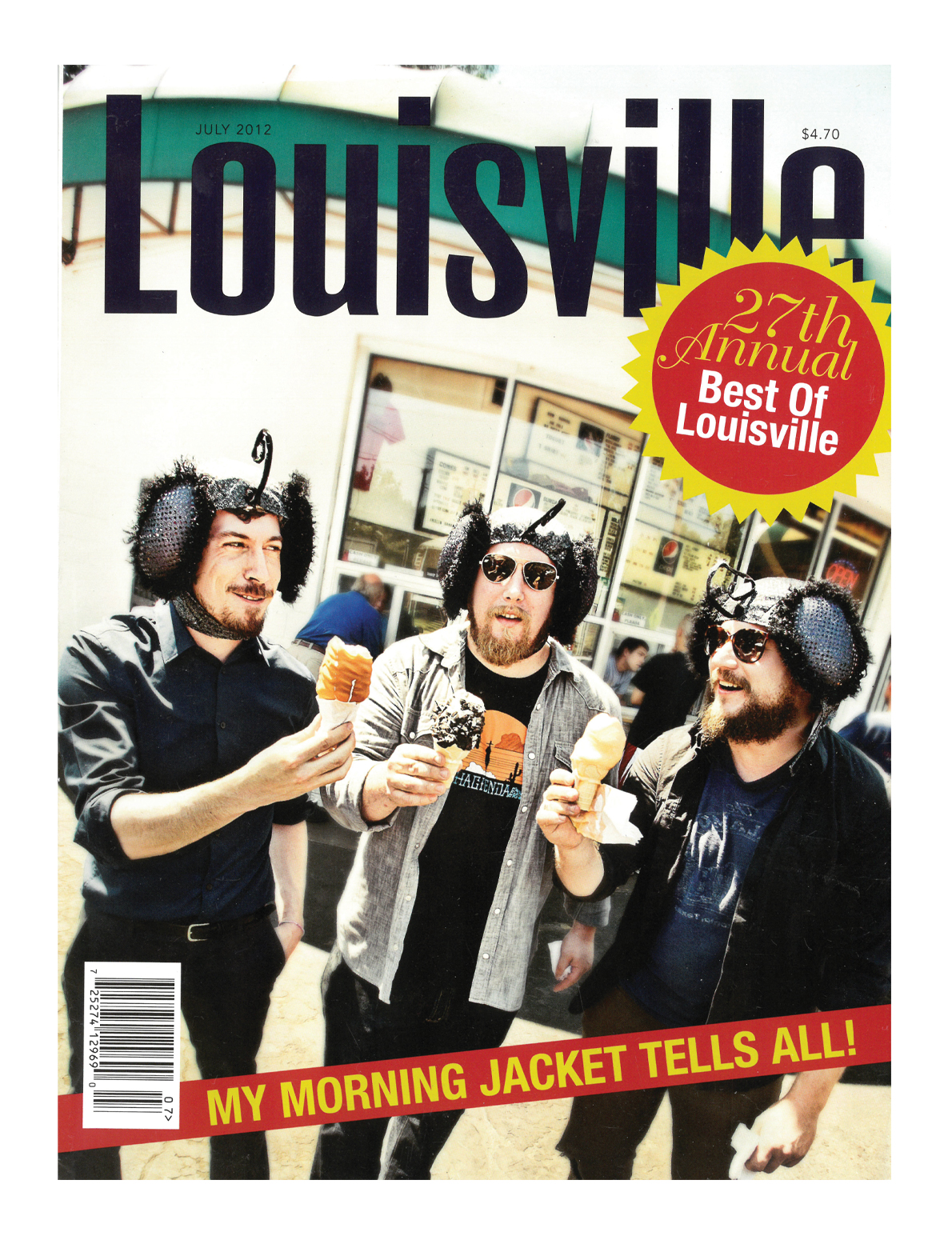

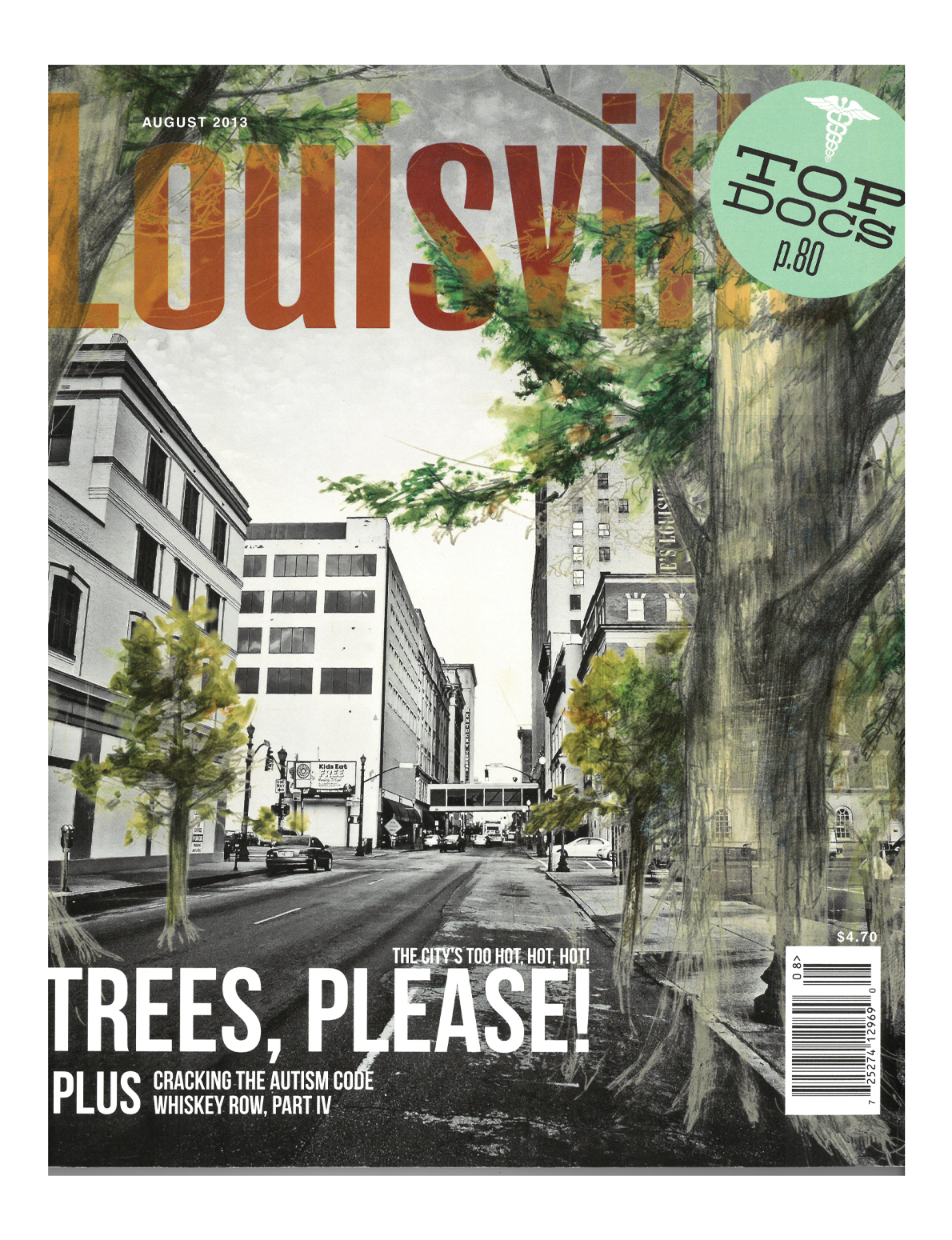

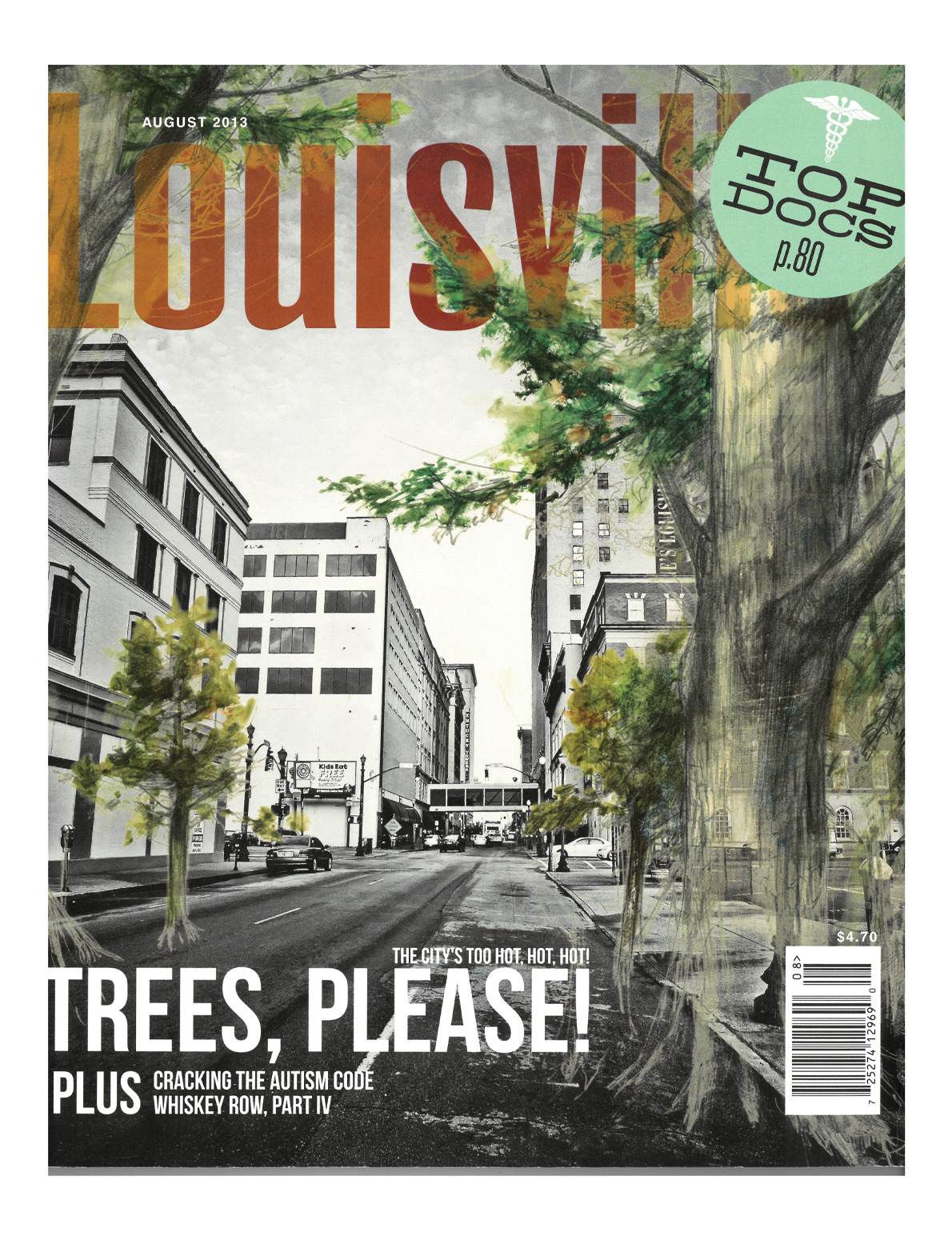

“This cover could still be featured today. If we showed you a map of tree canopy in Louisville, you would not only see where trees are in the city, but also you would see patterns of disease burden, income and urban heat. Living in greener areas has been linked to lower instances of heart disease, anxiety and depression. Low-income areas of Louisville have about half as many trees as the city’s average, and lack of tree cover can make a neighborhood more susceptible to urban heat-island effects. Trees also make air healthier to breathe by removing pollutants. According to Louisville Metro’s 2015 tree assessment, the city loses an average of 54,000 trees each year. Louisville is still getting hotter and still losing thousands of trees annually. We urgently need more trees to make Louisville a healthier and a happier place to live.”

.

Readers let us hear it about the May 2014 cover line highlighting the Rev. Al Shands’ art collection at his Oldham County residence, Great Meadows. We published their responses the following month, including words from Shands himself.

Readers:

“Wow. Impressive showcasing of your youthful hegemony on the cover.”

“With a bit more effort, you can surely work in some even more cutting-edge phraseology in future issues.”

“Offensive in the extreme.”

Shands:

“Thank you so much for the article about the collection. I thought it was great . . . and fresh. I have heard nothing but very positive feedback.

“The cover really did not bother me. I suppose its surprise value was its justification. It has made me realize that the term ‘kick ass’ has a current meaning for youth that it did not have 30 years ago. I had a friend who is about 90 look the term up in the dictionary to see what it means! The age gap becomes wider and wider in our fast-changing society.”

.

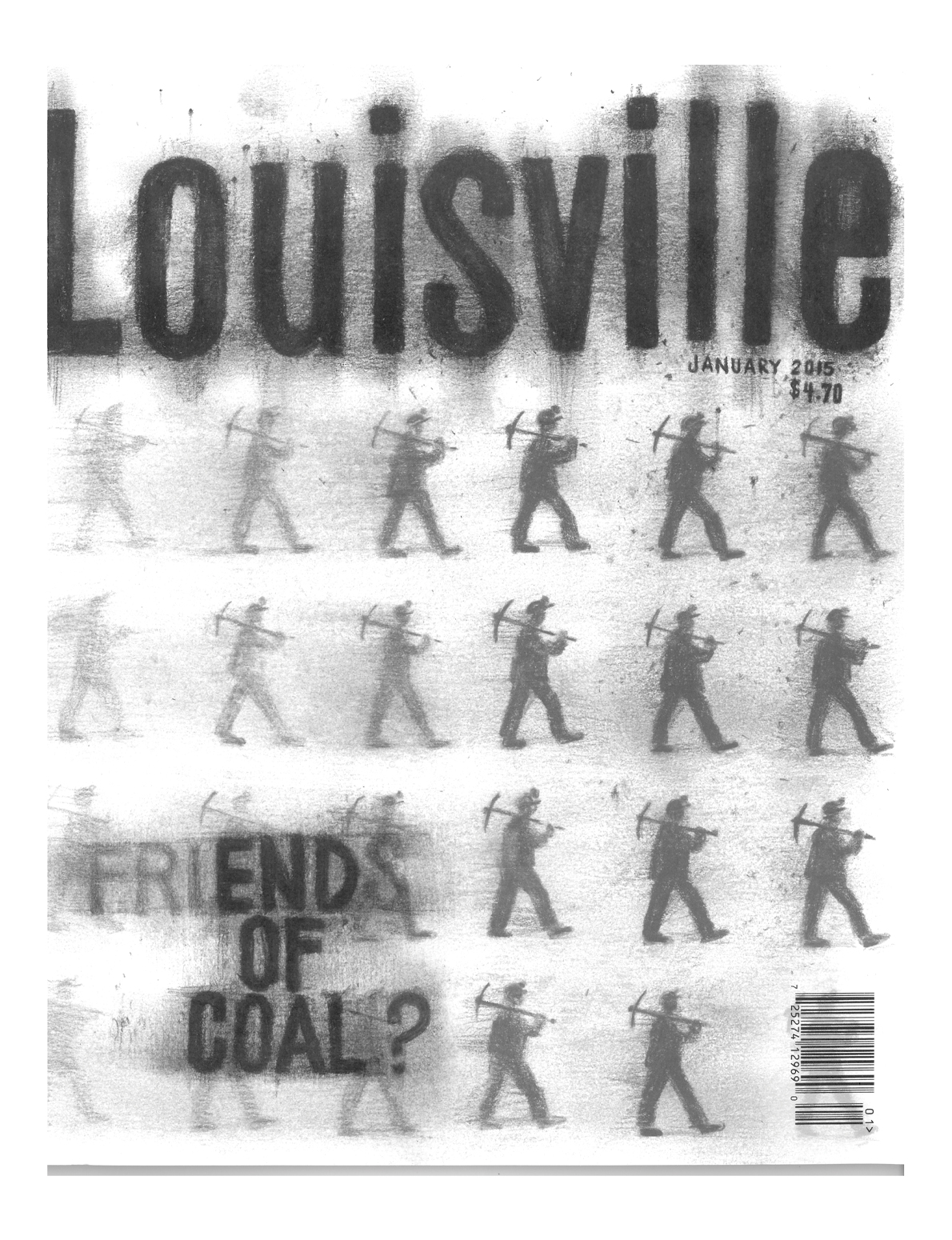

“Few issues connected to the Commonwealth of Kentucky have been — and continue to be — as contentious as that of coal. Debate has raged over all economic, political, social and environmental domains and, to date, no generally accepted pathway through these complex issues has been agreed upon. Mining in Kentucky reached its national prominence between 1973 and 1987, when the commonwealth became the nation’s leading producer of coal. In 1980, close to 60,000 people were employed in the Kentucky coal industry — a number that has declined to just over 6,400 as of 2019. Production, on the other hand, continues to increase relative to the level of employment due to the well-recognized increased mechanization of coal mining practices. Today, Kentucky coal still provides 73 percent of the primary electrical energy source for the commonwealth, a decline from 90 percent prior to 2010.

“Mining and the need for coal have evolved into somewhat of a paradox: On one hand, there is the image of the mining industry as being a long-time employer, the mainstay of family tradition and the backbone of a powerful cultural identity ingrained in the economic traditions of Appalachia and rural Kentucky. On the other, that of an exploitive, dirty and declining industry with little concern for miners, the environment and public health, and supported by a powerful industrial and political lobby.

“The cover succinctly engages these two dichotomous elements through superposition of the basic fundamental divisions: those that form supporting groups such as Friends of Coal and those that wish to see the end of this industry for the common good. The image of the miner smeared and darkened moving forward with the iconic miner’s pick, the lettering rendered smudged and imprecise, the juxtaposition of the caption(s) with the emphasis on End of Coal serve to express the nature and outcome of the mining industry. The systematic decline in coal production, employment and the economic losses due to a declining industry are due largely to factors beyond that of the industry itself. It is reasonable to expect that, along with mining itself, the use of coal as a primary energy source will continue to diminish. There will come a time when coal — as an industry, an energy source and a historic form of employment — will come to an end.”

.

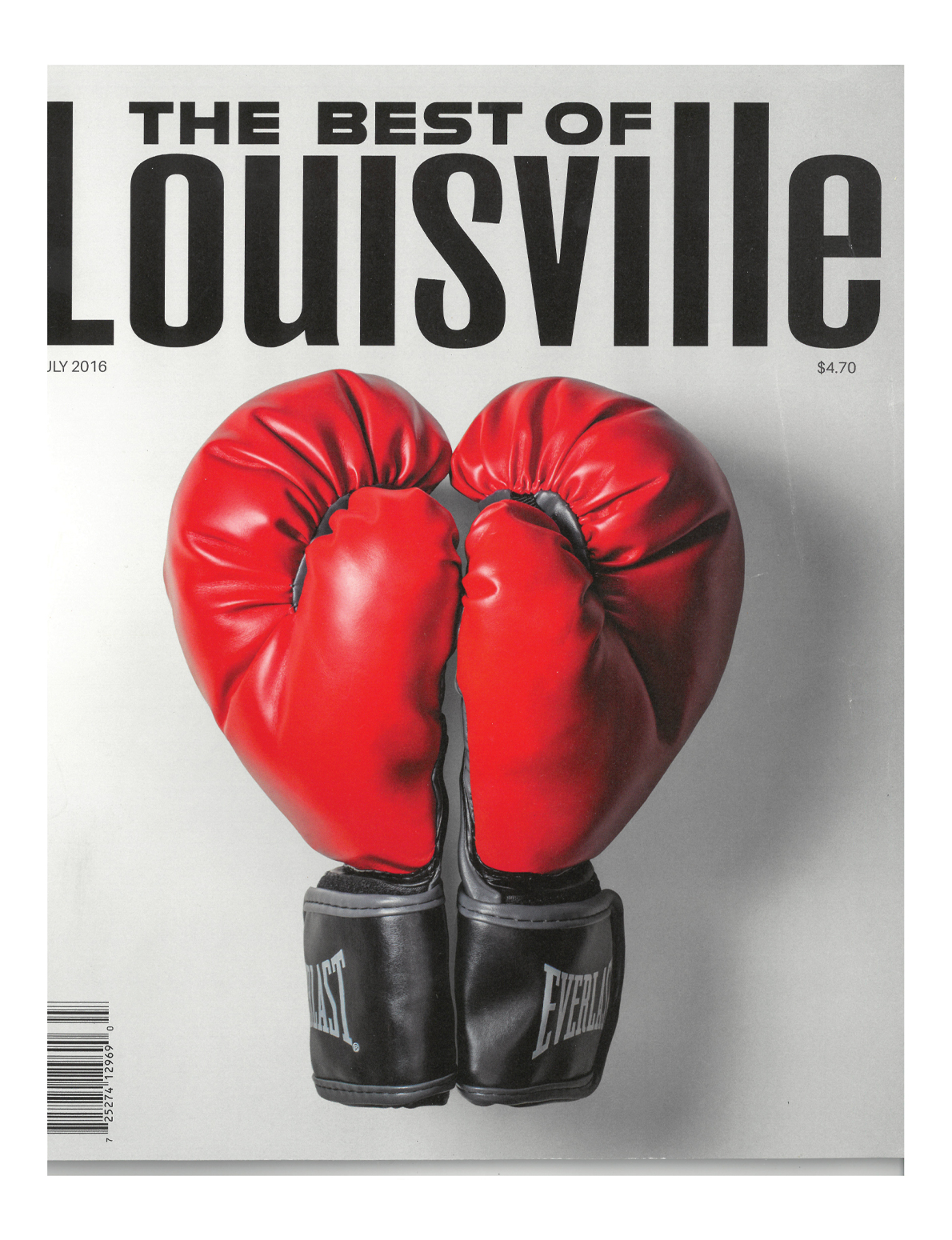

“I love how, to the untrained eye, this cover is just a pair of boxing gloves. But to those who know better, this is a picture of fire.

“It’s so important that Muhammad Ali was from Louisville; it’s both the beauty and the ugliness of our city that drove him to fight, both literally and figuratively. The fire that drove him into the ring with Louisville’s name on his lips time and time again is the same fire that continues to send Black Louisville into the streets with Breonna Taylor’s name on theirs. To me, this is a symbol of what it takes for the silenced and ignored to make it in this city and the world at large. This is a portrait of the West End, Shively, Shawnee Park and Portland. This is a monument to Black Louisville and the hands that picked up Ali’s fight once he had to put it down.

“If you are from Louisville, you instinctively know what this picture means. If you are Black and from Louisville, you know the way it feels.”

.

“The first time I met Sadiqa we were traveling to Portland, Oregon, for a Greater Louisville Idea Development Expedition event. After one of the conferences, we visited a local doughnut place, then headed for some fun at a karaoke venue. Sadiqa, who likes to be in front of a captive audience, put on quite a memorable performance! I was fortunate enough to capture a few of these moments on camera. To this day, Sadiqa and I kid each other that I still have video evidence and can bring it out anytime. Surely if you find her at an event and ask her about it she’ll tell you the song.

“Sadiqa is an iconic leader for the Louisville Urban League, and she drives a mission that expands far beyond her Urban League responsibilities. Her passion for our community shows in every meeting, event and gathering she attends. Sadiqa has a special talent for connecting at an individual level and builds connections no matter who she meets. Her championing and tireless efforts to launch and fundraise for the Norton Healthcare Sports and Learning Center in west Louisville has to be one of the biggest projects the Urban League has ever undertaken. Sadiqa’s energy and tenacity inspire me, yet she is a kind-hearted leader who — for anyone who knows her — is family-centered with her children. She never gives up seeking to do good in our beloved Louisville.”

.

“I started my singing career in the West End, and Syl’s Lounge has been one of my hangouts for many years. Miss Syl is like family to me. On karaoke night, she always requests for me to sing ‘One in a Million You,’ by Larry Graham. I’ve always thought she was one in a million and look forward to singing the song for her again.”

.

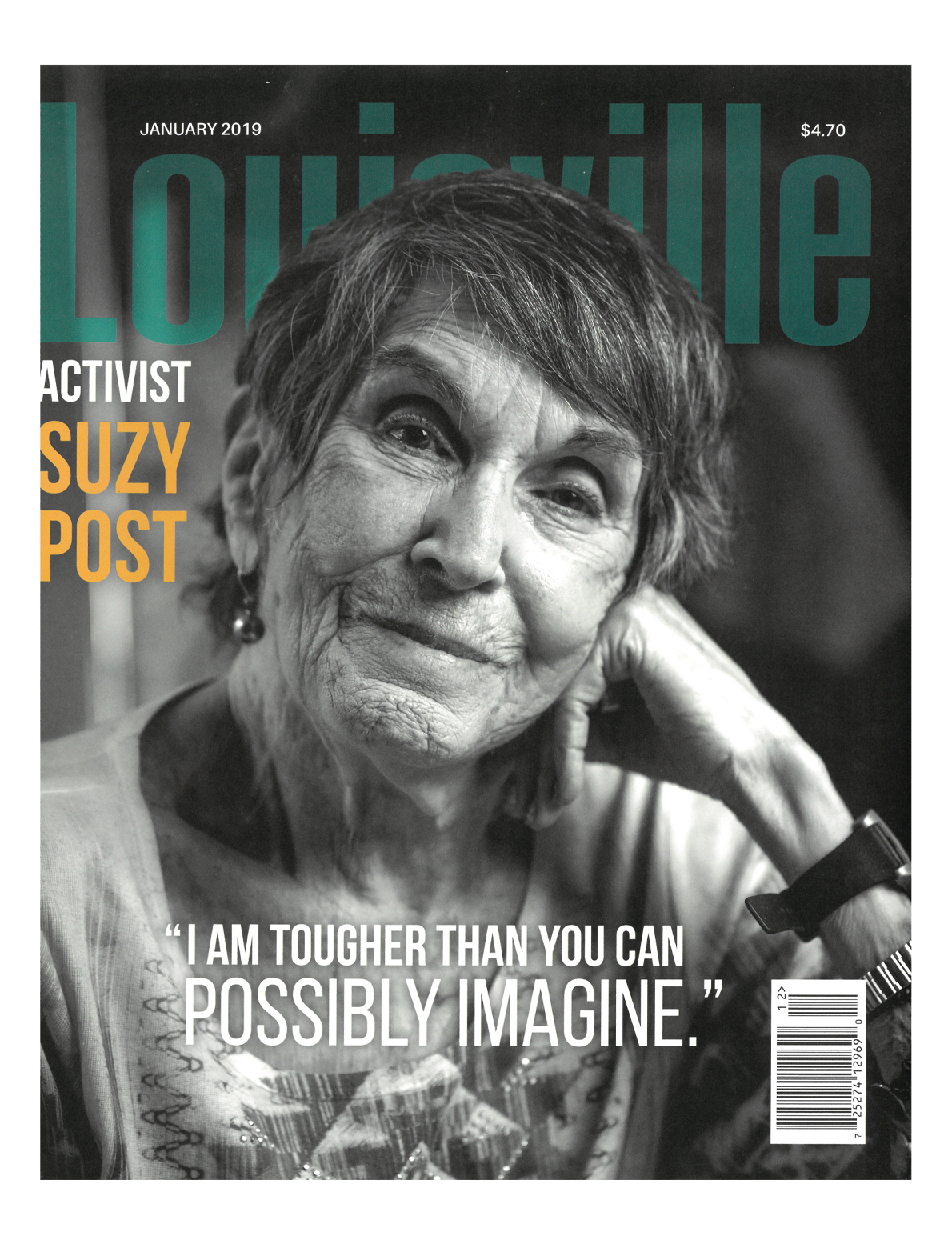

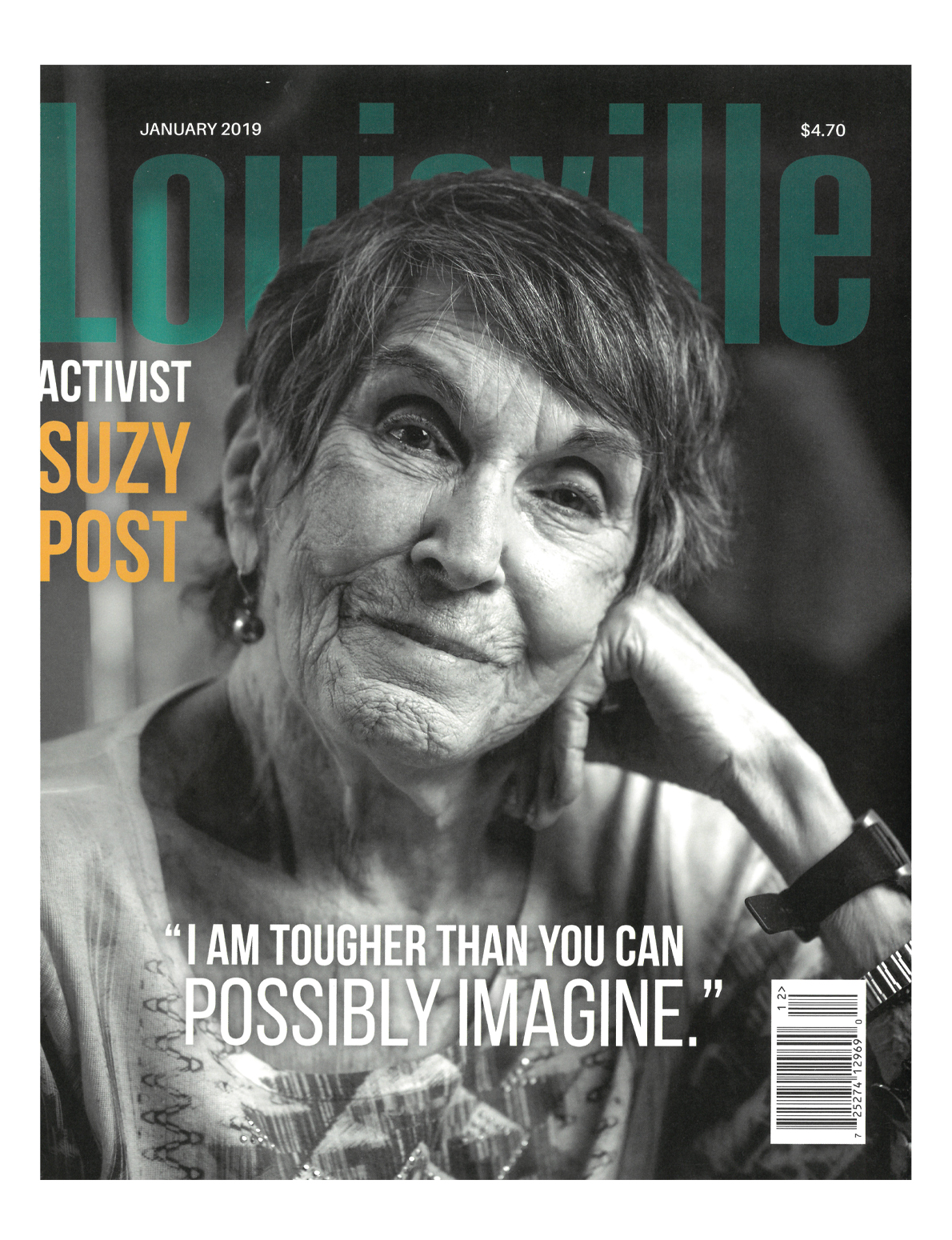

“Suzy Post was a mentor to me and legions of social-justice advocates in Louisville and beyond. She had an indomitable spirit that would never let her sit on the sidelines when injustice was rearing its head. Whether it was leading the ACLU of Kentucky and creating the Reproductive Freedom Project to protect access to abortion, or running the Metropolitan Housing Coalition advocating for fair housing for all Louisvillians, her restlessness got things done. She wasn’t afraid to tell me when she thought I was wrong, but she did it because she cared about me and she cared about the issues we continued to work on together. She once told me, ‘It’s wonderful to know that your life mattered,’ and hers certainly did.”

.

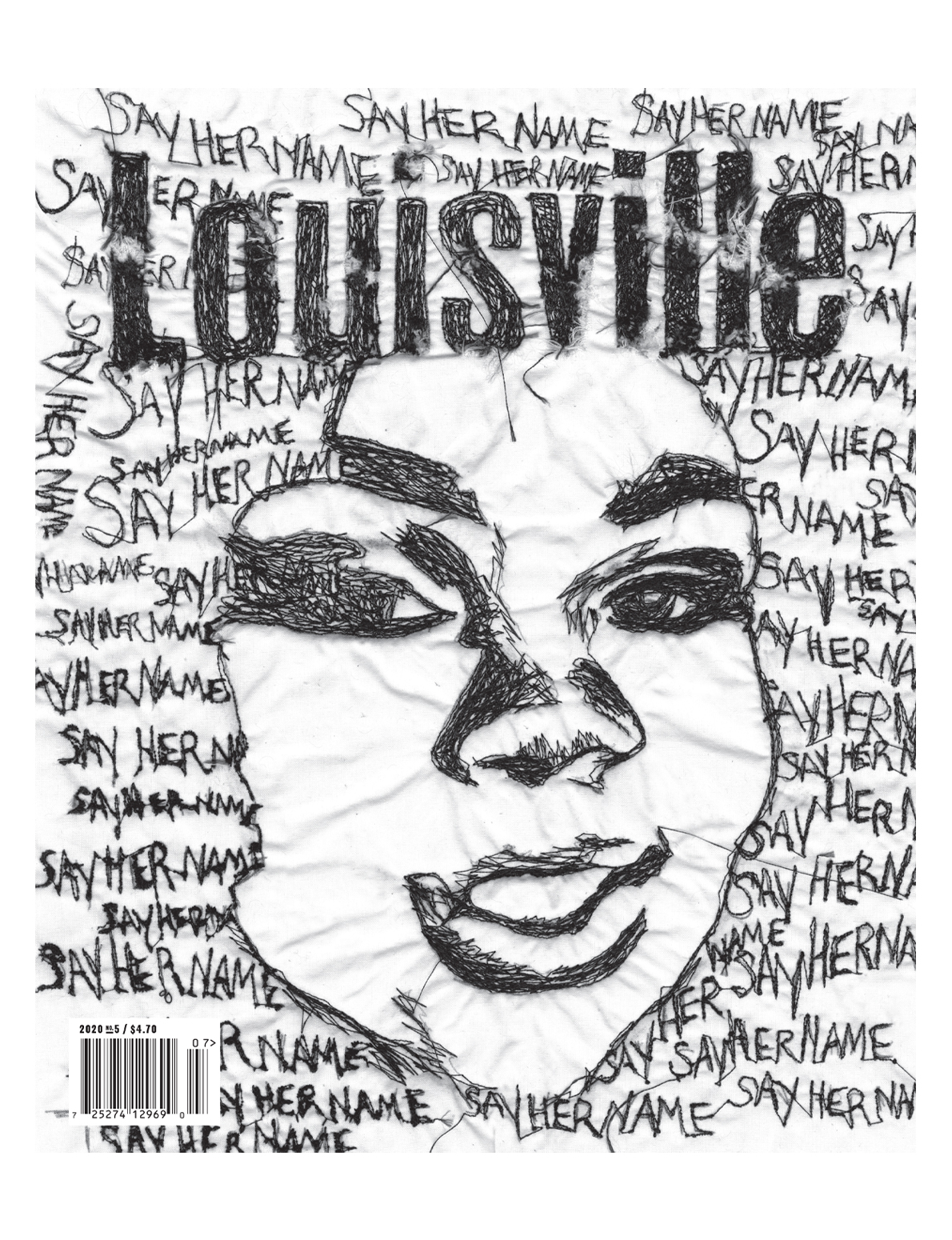

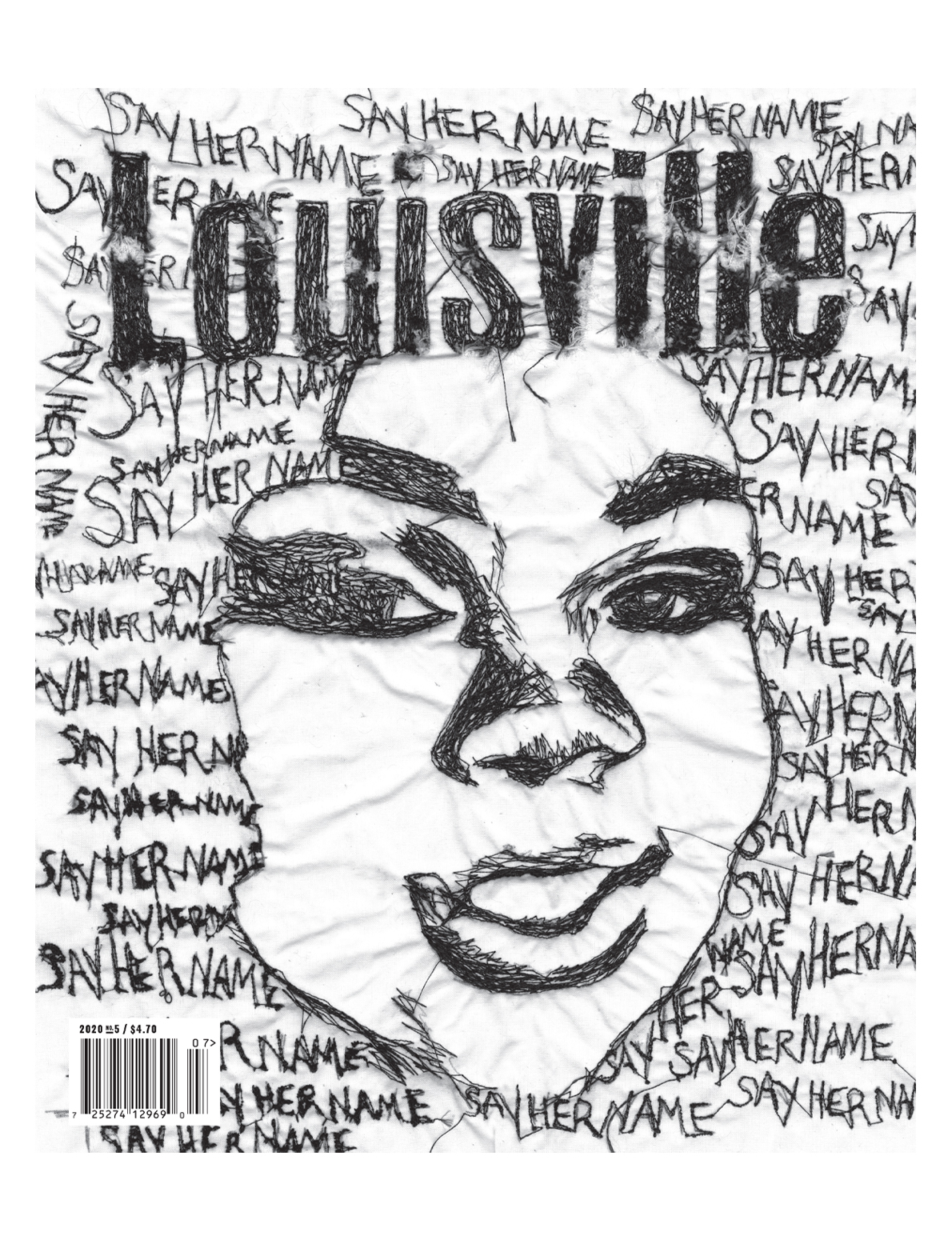

“Honestly, I never opened this issue. The collective trauma to defend her, the way the words literally formed her existence. I was burned out on the fight. Exhausted is probably a better way to phrase it. I didn’t know if the issue would be speaking about the greater problem or if it’d focus on capturing all the dialogue taking place, but truthfully, I didn’t care to read or see another piece on the case. Because the facts were just so simple to me.

“Now that some time has passed, I can better connect with the imagery, and it is easier to look at. But it is just a memory of very timid times for me.”

— Nikayla Edmondson, Louisville Magazine contributor, who, for the last issue of 2020, helped lead a project that featured the stories of 26 Black women from Louisville in their mid-20s. (Breonna Taylor was 26 when LMPD officers shot and killed her in her own home during a botched raid.) Each woman — Nikayla included — got her own cover.

Share This Article

We want to hear from you. Who or what should more Louisvillians know about? Share here.