In Jefferson County, 4,000 to more than 5,000 households get evicted every year. This is the story of those who witness it, and of two people caught in the spiral.

Marshall did some updated reporting on this issue last year. Read here.

A black rolling cart hauls a stack of bubble-gum-pink folders to the third floor of the Hall of Justice downtown, landing in the lap of eviction court. Below, on the first floor, the 8:45 a.m. push of people files in through metal detectors, a march of mostly reluctant faces. Deputies’ wands drift over limbs extended like starfish, beeping at pocket change, ankle monitors, belt buckles and hip replacements.

Those here for eviction court arrive on the third floor and squint at the docket taped outside the doors, checking for their name, then typically retreating to gray metal benches with holes the size of pencils. There’s a seriousness of place here: stocky granite pillars, police officers, briefcases and, beyond a corridor of courtrooms, glimpses of daylight through a set of windows.

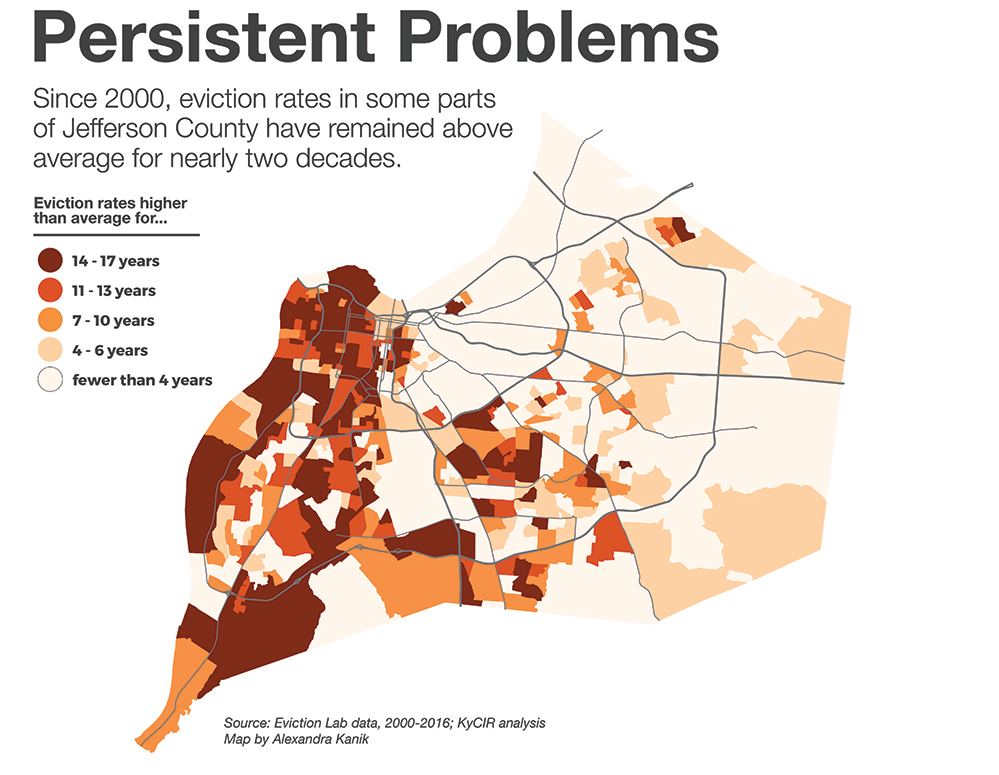

In 2016, 5,761 rental households were evicted in Jefferson County, putting the eviction rate at 4.49 percent of renter-occupied homes. That’s about double the national average. In certain parts of west and south Louisville, the rate has long been much higher. Take the north-central section of Russell, a largely African-American part of the city in west Louisville where 30 percent of residents live in poverty. The eviction rate in 2016 was nearly 8.5 percent. And 25 percent of the 186 rental households in that area had an eviction filed against them, though not all of those filings ended with a set-out. (Data in this story provided by the Eviction Lab, Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts, Metropolitan Housing Coalition and the Kentucky State Data Center.)The first-timers often sit stiff-backed with nervousness, unsure of what’s to come. Because evictions are held in civil court, not criminal court, renters have no right to a public attorney. Most renters — 85 to 90 percent of them — don’t even show up. When that happens, the judge grants the landlord, who usually does have legal representation, a default eviction judgment, meaning if the tenant isn’t gone in seven days, the sheriff receives the cue for a “set-out” — that indelible final act when a home is essentially turned inside out, any and all contents left huddled on a curb.

In the southwest corner of west Louisville’s California neighborhood, where California meets the Park Hill neighborhood, 45 percent of residents live in poverty. In 2016, the eviction rate was nearly 16 percent. A majority of the 294 households in this area are rentals, and 27 percent have had evictions filed against them. In these high-eviction pockets, an abundance of rentals line streets, homeowners sticking to more stable neighborhoods.

Outside the Hall of Justice, several blocks away, floodgates shove back the Ohio River, which is rising following relentless rain. Inside, it’s chilly on this late-February morning. Annie Dixon, a mother of three boys wearing jeans and a navy winter coat, slides into the second pew. Thirty-year-old Da’Marrion Fleming, who just dropped off his eight-year-old son at school, is bleary-eyed from an overnight shift as a front-desk supervisor at a hotel. He takes a seat behind Dixon. Both have faced evictions before. Dixon and her husband were evicted back in 2003, then again in 2012. Fleming’s history is more complicated.

Judge Erica Lee Williams calls Dixon’s name first. Dixon, a 34-year-old with pale skin and blue eyes, squeezes past other tenants. “Hi, I’m Annie Dixon,” she says to Williams, one of two judges (the other being Sandra McLaughlin) who have regularly presided over eviction court for the last several years and consistently since last summer. Williams has signed so many eviction judgments and dismissals (along with other court documents) during her nine years as a district court judge that her signature has condensed from a full “Erica Lee Williams” to just a bubbly “E” with a dash.

“Did you receive notice to leave?” Williams asks Dixon.

“Yes,” she says. “Can I explain my situation?”

Dixon’s case is known as a holdover — an eviction not involving payment but a tenant’s refusal to leave. Dixon had worked as a leasing agent at a south Louisville apartment complex. With that job, she was able to live on-site in an $850 three-bedroom apartment for about $200 a month. Her position was eliminated. The work contract she signed indicated that if she’s not employed at the complex, she doesn’t necessarily get to keep the apartment.

Dixon’s a fast-talker. When given a chance to speak, her thoughts lock elbows and rush forward. “I don’t have a job. My husband doesn’t have a job,” she begins, her voice cracking. She lifts her hand and fans her face, shooing off emotion. “I’m sorry,” she says through a rush of tears. “I have no place to go. I can’t get a new place because I have an eviction. I’m a leasing agent. I know all about that.”

Williams listens to Dixon, then asks that she and the attorney for the apartment complex step into the hallway. Perhaps an agreement can be made, one that will avoid another eviction on Dixon’s record. Both Williams and McLaughlin encourage these settlements, especially if they sense someone is down on their luck but trying to rebound.

Dixon and the lawyer, Michael Calilung, a 22-year eviction court veteran with black-framed glasses, a shaved head and so many clients he can’t keep count, pair up in the hallway for several minutes. Dixon’s embarrassed. She used to speak to Calilung on the phone when she worked as a leasing agent. She recognizes his voice, with its slight accent from his native Philippines. Calilung would call to relay upcoming eviction court dates to Dixon’s boss. Now Dixon’s the one they’ll be talking about. “It’s nice to put a face with a name,” she says, politely.

The agreement: Dixon has until March 14 to move out. If she does, case dismissed. Before walking away, Calilung reiterates: “If not, we’ll file a warrant of possession that day.” The warrant is what the sheriff needs to arrange a set-out. “OK,” Dixon says, nodding. A few moments later, she mutters, “Hopefully I find a place.”

Da’Marrion Fleming hunches in the pew, his stocky build designed by years playing on football teams, from the “pee-wee” California Park Jets to freshman year at Tennessee State University. Fleming is a familiar face in west Louisville. A few years ago he started his nonprofit Sowing Seeds with Faith, and it has grown to tutor and mentor hundreds of kids. Other than his two sons, the nonprofit is his baby, his purpose. In the courtroom, an older man Fleming knows from church, a landlord, nods and the two greet each other. What an uncomfortable place to be spotted, Fleming laments.

Fleming had hoped his December visit to eviction court would be his last. Attorney and metro councilwoman Jessica Green represented him. The Portland apartment he lived in, owned by Mirage Properties, had raised his rent from $400 to $750 and told him that if he didn’t pay it, he’d have seven days to leave. Even though Fleming was without a lease, by law Mirage had to give him 30 days notice for a rent increase. “This sounds to me like a landlord trying to squeeze out low-income people,” Green argued. The case was ultimately dismissed.

Hardly any renters come to court with an attorney. “I showed up because I know him and I like him,” Green says. “I did it for free. Most don’t have money to pay for lawyers.” The few who do have counsel, like Fleming, have a significantly higher chance of working out a deal with the landlord or getting an eviction dismissed.

Legal Aid fields many requests for help but can’t tackle everything. In 2017, it assisted 1,340 adults and 1,030 children tied up in eviction proceedings. Most of the adult clients were female, 44 percent of them black and 20 percent of them single mothers. Every year for the last 10 years, between 16,300 and more than 17,600 evictions have been initiated in Jefferson County, according to court records. Of those, depending on the year, anywhere from 4,000 to more than 5,000 households wind up with an eviction judgment.

Last year, New York City committed $155 million to ensure low-income tenants would have legal representation in eviction court. Evictions have declined in New York by 24 percent, with representation climbing from less than 10 percent to 27 percent. Durham, North Carolina, recently started an eviction “diversion” program, staffed by Legal Aid lawyers and Duke University law students.

For four years, a paralegal from Legal Aid sat in Jefferson County eviction court every day. The Tenants in Crisis program helped renters find emergency housing and occasionally brokered deals between landlords and tenants. Staffing changes at Legal Aid and a loss of federal funding ended the program in 2013. A Legal Aid attorney is supposed to attend eviction court daily, but the workload is so heavy that scheduling conflicts often arise.

The moment Fleming’s case was dismissed this past winter, Mirage followed up with the proper 30-days notice about hiking up his rent. Fleming says it rose to $900. He felt wronged and didn’t pay January’s rent. “It’s Portland,” he’d explain later. “And there were several substantial issues, maintenance issues that were never dealt with.” Having lived in the place for seven years, Fleming’s record shows six other evictions filed (prior to today’s) since 2012, though he was never set-out. Fleming was late a lot with his rent, especially, he says, when going through a custody battle for his oldest son a few years ago and right after college, before he secured work as a teacher and coach with Jefferson County Public Schools. His landlord filed for each eviction, and a sheriff’s deputy came and taped what’s called a “forcible detainer” to his door — mailed him a copy too. With roughly 17,300 forcible detainers filed last year, one deputy might post up to 70 in one day, nicknaming them “lick-em-and-stick-ems.” Forcibles give tenants an eviction court date and list how much they owe their landlord or whatever reason they’re being evicted.

Fleming paid the landlord before having to go to court, so he never got kicked out. He thought all was said and done. But the fact that a landlord sued him at all has scarred his rental record. Same holds true for those who work something out with the landlord after they’ve had their court date. Deputies may not get tapped for a set-out, but that eviction pops up when landlords perform tenant screenings. If an agreement has been reached, landlords can file paperwork with the court that erases an eviction from a renter’s record, known as a “set-aside.” A majority do not. Some landlords who find themselves in eviction court frequently think: The tenant was late on their rent. They’ll probably be late again. Why bother?

Frequent names pop up in eviction court, tenants who know they can ride rent-free for a few months before the sheriff expels them. But most carry the burden of job loss, illness, death of a loved one, a forever shuffle of prioritizing what to pay — bills or rent and, come the holidays, gifts so family can wake to a nice Christmas morning.

In Fleming’s case, the property has changed management a couple times. He tried to contact the property owner to request a set-aside on his evictions. He says he wound up on the phone with a man in Sacramento, California, who said he had “owned property in Kentucky” but sold it and didn’t know how Fleming could contact the property management groups who initiated the evictions.

Judge Williams calls Fleming’s name. Holding a red knit cap in his hand, he walks to the podium.

“This says rent in January isn’t paid,” Williams says.

Fleming shares his plight: the rent spike, his rental record. “How am I supposed to find a place to stay?” he asks.

“I don’t know,” Williams says. “But we are here because of January’s rent. I’m going to grant judgment.”

Fleming has seven days to find a new place before the warrant of possession is filed. In the hallway, he catches a lawyer. “Do you know how I can get these evictions off my record?” he asks.

“I work for Mirage, so I cannot give you legal advice,” the attorney says before returning to the courtroom to finish out the day’s docket.

Landlords sue tenants over money — to cover mortgage payments, maintenance. Maybe rental property is how they make their living. An eviction costs a landlord a little more than $85, plus legal fees if they hire a lawyer. “Oftentimes what you don’t see (in eviction court) is that the landlord has worked with these (renters) a long time,” judge McLaughlin says.

She says most landlords are good people. Sometimes they’re lenient, routinely accepting late payments, a practice McLaughlin advises against. “I tell them, ‘Make sure you collect that rent on the first of the month,’” she says. “That money will go somewhere if you don’t get it, and then they cannot get caught up. So you’re actually hurting people by not getting rent money on the first of the month.”

Eviction has received heightened attention in the last several months, largely due to the Eviction Lab at Princeton University. Having compiled 83 million records from across the country, dating to 2000, the Eviction Lab created the first nationwide eviction database. (Matthew Desmond, a sociologist whose 2016 Pulitzer Prize-winning book Evicted chronicled the lives of poor renters in Milwaukee, leads the Eviction Lab.) According to Eviction Lab data released in April, North Charleston, South Carolina, has a 16.5 percent eviction rate, the highest of any city with a population greater than 100,000. Louisville ranks 42nd. These rankings, of course, only capture formal evictions. Nobody can track renters who flee due to misunderstanding the eviction process or threats from a landlord.

Some landlords gripe about the eviction timeline. It can take 45 days to two months or longer to evict someone — from the time a tenant first receives a formal letter warning that rent is past due or that they have violated thier lease to the day a sheriff comes knocking on the door. Occasionally landlords go around the system. Last year, for example, a landlord was caught posting fake eviction notices with the sheriff’s logo on it. He was charged with forgery.

Absorb eviction court from the pews, and the process tilts largely in favor of the landlord. One morning, an 82-year-old woman shuffles to the podium with her son. She wants to stay in her apartment but her lease has expired. The property owners want her out, presumably to renovate, so they gave her proper notice and stopped taking her rent.

“Why don’t you just accept her rent and I’ll help her find another place,” the woman’s son asks.

“No,” the lawyer responds.

On another day this spring, a woman dressed in the kind of playful, patterned scrubs you might see at a doctor’s office or nursing home is being charged with a $275 fee for each month she was late on rent, deepening her financial hole. Judges can and do sometimes forbid steep late fees, but in this case the judge, tenant and landlord’s attorney have devised an agreement: Pay the landlord $3,000 for the two months of late rent and a host of fees (her rent is $1,300) and the landlord will scrap the eviction. This is a Wednesday. She has until Friday.

Assistance exists if you know where to look for it. Once a calendar year, Neighborhood Place centers will help a renter in need. Applicants must live at 150 percent below the poverty level (about $36,500 for a family of four) and meet a list of requirements. In 2017, Neighborhood Place served nearly 2,100 individuals, about double that of previous years due to a larger budget. Several community ministries offer between $100 to $300 for rental assistance, hardly enough to cover a full month’s rent, and the money tends to run out fast.

Since 1996, Volunteers of America has helped public-housing tenants facing eviction, last year keeping 250 adults and 100 children in their homes. Affordable-housing developer Chris Dischinger, of LDG Development, recruited VOA to provide eviction-prevention services at one of his properties in Fern Creek, a novel thing for a private landlord. “If we can have stable residents, then we can have less turnover,” Dischinger says, adding that an eviction can cost his company “two or three thousand dollars by the time they move out. We have to repaint, re-carpet, fix up the unit (and) it’s going to sit empty for a period of time.”

Some renters come to court ready to fight an eviction. They grip photos, evidence of a landlord’s alleged misdeeds — mold or exposed wiring, a ceiling that’s partially collapsed. “Before I came to Legal Aid I would’ve never imagined that it is a regular thing for sewage to come up through bathtubs, but I hear it all the time,” says Stewart Pope, Legal Aid’s advocacy director, who represented renters in eviction court from 2000 to 2005. “I couldn’t tell you how many times ceilings have fallen and injured people. This is stuff that most of us wouldn’t want to sit down in, much less live in.”

In court one day, a young dance coach clutches a blue folder of pictures showing cracks in her walls that allowed water to seep in. The landlord wouldn’t fix it, so she withheld rent. At the podium, she doesn’t mention the walls. Maybe it’s nerves. This is her first time in court. Earlier, her hands trembled in the hallway. The judge rules in favor of the landlord. (A renter can file an appeal on a judge’s eviction ruling, but it costs $70 and all owed rent must be paid in full with the courts.)

Even if the woman had brought up the walls, it probably wouldn’t have mattered. Take it to small-claims court. “This is about payment,” the judge may have said. There’s a process for dealing with bad landlords written into Kentucky law. Renters must give a landlord written notice (not just verbal) about health or safety hazards. The landlord then has 14 days to fix the problem. If they don’t, a renter can pay to get it remedied, save the receipts and deduct the repair costs from rent. Judge McLaughlin says she cannot recall “one tenant” who has known to follow this procedure correctly. (A tenant can stop paying rent if water, electricity, gas or heat are not functioning through no fault of their own and the landlord refuses to address the matter.)

Some landlords ignore repair requests, instead relying on desperate tenants and cheap rent to keep units occupied. If a tenant stops paying rent due to bleak conditions, an eviction is filed. Another low-income renter can fill the vacancy. Slumlords, some might say.

“Before I came to Legal Aid I would’ve never imagined that it is a regular thing for sewage to come up through bathtubs, but I hear it all the time,” says Stewart Pope, Legal Aid’s advocacy director. “I couldn’t tell you how many times ceilings have fallen and injured people.”

In eviction court, you can mention the name Shirley Haycraft to anybody — judges, clerks, deputies who set out tenants. They all know her. Until recently, the 75-year-old, who owned about 50 properties, was filing eviction paperwork once or twice a week. In May, the Jefferson County Attorney’s office finalized an agreement with Haycraft designed to get her “out of the business of being a landlord.”

She pleaded guilty to three charges, including one of wanton endangerment stemming from conditions at her properties — live electrical wires coming out of the ground, no operating fire alarms, leaky roofs, pest infestations, ignoring an “order to vacate” notice. As part of her two-year probation, Haycraft cannot purchase any new property and must maintain her vacant properties and fix up those in disrepair. She was fined about $2 million — a figure the county attorney’s office called a “conservative estimate” when you add up all the daily fines owed on multiple code violations. She doesn’t have to pay it if she improves her properties and avoids further violations. And $50,000 will be deducted from the $2 million for every property she sells.

Regarding her sentence, Haycraft says, “I don’t know if you could call it fair.” She’s adamant that many of the violations she’s been cited for are due to new, hyper-vigilant inspectors motivated by collecting fines. Haycraft believes she has always been a good landlord. “I’ve been one for 30 years. I must have been (good) or I wouldn’t have been one for 30 years,” she says, adding that the sentence isn’t weighing on her. She says she had planned on selling all her properties anyway and moving to Florida.

In eviction court, when word spread of Haycraft’s sentencing, eyes popped. And yet Haycraft’s lasting legacy in eviction court may date to 2014. She had lost an eviction case. Judge Williams dismissed it, stamping the paper with a black DISMISSED stamp that measured about an inch. Haycraft got a copy of the judgment and allegedly tore out the piece that read DISMISSED. That eviction notice then got posted to her tenant’s door.

The renter alerted the courts in confusion, thinking her case had been dismissed. Williams found out, sentencing Haycraft to 60 days home incarceration, along with a $500 fine. (Haycraft says this incident never happened, and she was put on home incarceration due to a disagreement with a tenant during court.) Williams wanted to ensure nobody would ever fiddle around with eviction judgments again. “I decided I wanted a big red obnoxious stamp,” Williams says. The first replacement was close to three inches and red. “Bigger,” Williams said. A red DISMISSED stamp, slightly smaller than a chalkboard eraser, debuted in eviction court.

Dixon is back in court on March 14, the day her landlord said he would file a warrant of possession if she hasn’t moved out. Dixon sips orange juice from a bottle and heads into the courtroom, wearing black dress pants and a colorful blazer. Her sandy-hued hair is curled and pulled back with a gold headband. Her oldest son, Micah, in a Misfits jacket and black jeans, sits with his mom, occasionally closing his eyes and sinking his head into his hands. Things are little better than they were two weeks ago. Through a temp agency, Dixon is now working as a leasing agent at an apartment complex in Okolona. When Dixon’s name is called, she stands and wobbles.

“Sorry, my foot fell asleep,” she says, stomping.

“That’s the worst,” judge Williams says, in a tone that’s empathetic and light.

“It’s coming back,” Dixon says, hobbling to the podium.

“Tingling and burning yet?” Williams says, smiling.

Dixon’s case is on what Williams likes to call her “two-second docket,” reserved for landlords and tenants who came to an agreement and passed the case for another day. If the tenant hasn’t abided by the agreement? Evicted. Only one or two seconds needed.

Dixon: “How you doing today?

Williams: “I’m good. Did you vacate?”

Dixon: “No, not yet. My husband has a good job. I also got a job working at one of the top luxury apartments in Louisville. I’m one of the leasing agents there. We just haven’t had a full paycheck yet. I’m asking if (the landlord) can please give us until next week to vacate so we can have money to do everything. I don’t know if you have kids. If you could do it for him,” Dixon says, gesturing to Micah.

Williams: “Why isn’t he in school?”

Dixon: “He’s my support. He’ll be there in two minutes. He’s 17. He’s allowed.” Dixon is particularly close with Micah. Both are talkative and sincere. He offered to come, even helping her choose her outfit.

The lawyer, Michael Calilung, listens to Dixon with his mouth zipped in a straight line. He couldn’t keep doing the work if he internalized each struggle. When children are involved in an eviction, he leans on this logic: “Between the landlord and the parents, who should really be concerned about keeping a roof over that child’s head?”

Calilung: “We are asking for the judgment.”

Dixon whimpers. “But it’s going to be on my record,” she says. She worked at the apartment complex she’s being evicted from for five years. What if her friends and former coworkers see her being set-out? “It’s baloney. I’ve put my sweat and tears” — she trails off, sobbing.

Williams: “I’m certainly sympathetic to your situation. I am. It’s just not up to the court’s discretion. You all had an agreement. If I could do something, I would. But I can’t. My hands are tied. So I’m going to grant the judgment. I wish you the best.”

“Sheriff’s office!” A fistpounds the door — bang, bang, bang, bang, bang. A set-out begins. Monday through Friday, one eviction per hour, starting around 8:30 in the morning and ending in the early afternoon. The only downtime comes around Thanksgiving and Christmas, a courtesy to families. Deputies get swamped in January. Warmer months can prove hectic too, as some landlords like to sweep out unreliable tenants and secure better ones before winter descends and LG&E bills balloon.

Every day at 9:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m., a clerk from the sheriff’s office walks across the street to the Hall of Justice, toting back a pile of papers to the fifth floor of the sheriff’s office, where a woman in a pink cubicle bundles the warrants of possession and schedules set-outs for a specific day and time, stamping it on the warrant in red — the “scare date,” deputies call it. Deputies usually don’t show up until at least a few days past the scare date.

Often, renters have vacated by then, leaving evidence of a life interrupted — clothes, shoes, half-full liters of soda, crusty kitchen pots, a funeral program, coupons, loose tobacco cascading from coffee table to carpet. Deputies have found a boa constrictor and a pot-bellied pig. They must confiscate any weapons, pornography or drugs. The smell in abandoned rentals can overwhelm — garbage and old kitty litter are a stale, potent duo. No one is supposed to open the fridge, especially in the summertime.

Louisville’s “fair-market rent” for a two-bedroom is about $820. A renter would have to earn at least $15.90 per hour to cover that without being cost-burdened. Louisville’s minimum wage is $7.25.

At public-housing complexes, deputies in brown and tan uniforms complete set-outs one after another, back to back to back, up to a dozen at one site. Louisville Metro Housing Authority owns and manages nearly 3,600 public-housing units. According to the Louisville Apartment Association, LMHA is Louisville’s largest landlord. They’re also a frequent evictor. Occasionally LMHA will evict for as low as $25 in owed rent. But that $25 may represent five months of unpaid $5 rent and a failure to put even a few bucks toward the debt. Because LMHA is the housing of last resort for many, LMHA says if a tenant is evicted due to nonpayment or lease violation, it’s not a scarlet letter. They can reapply.

This spring, Katina Powell, the infamous escort whose book Breaking Cardinal Rules shattered the University of Louisville’s basketball program, makes an appearance in eviction court for a lease violation: Her daughter had reportedly pulled a .38-caliber handgun on a man who was near the LMHA property where they lived.

On that same day, Lynda Graham, the mother of Thaddeus Thomas, one of four teens accused of robbing and murdering a man in Cherokee Triangle last November, is evicted from the Parkway Place housing projects. Thomas wasn’t supposed to be living with her at Parkway due to several run-ins with police, and LMHA had evidence that Graham’s apartment was Thomas’s main residence at the time of his arrest on murder charges last fall. Upon being evicted, Graham crumples on a bench outside the courtroom, crying. “It’s too much,” she says, pounding a fist into her palm. Three of her other children and an infant granddaughter live with her.

“This isn’t a happy day for anyone,” Graham’s Legal Aid attorney says to her, promising to try and get her extra time to move before a set-out is on the books.

If tenants are home when deputies pull up, evictions still usually go smoothly. But not always. On a gray, cold February morning, a stinging, wet air speckles ice on branches, steps, sidewalks, everything. Deputy Jon Pfeifer, who has spent much of his 18 years with the sheriff’s office working on evictions, arrives at Autumn Lake Pointe trailer park in Valley Station, figuring the set-out might be contentious. The man, Richard Eckhart, owns the trailer. He has been out of work for a while, has struggled to come up with the lot fee. He claims the trailer park owes him $900 for some maintenance jobs he had completed on-site. (It’s common for tenants to work off rent they owe, but without a written agreement, any deal carries little weight in court. A spokeswoman for SSK Communities, the owner of Autum Lake Pointe, says Eckhart is not owed any money and stresses that evictions are a “last resort” for tenants far behind on payment.)

Eckhart explodes when Pfeifer knocks on the door. Angry and flustered, he speeds off in his Chevy pickup. “I guess he didn’t think it was gonna happen,” Pfeifer says. “But it’s not like he didn’t pay one month. He hasn’t paid (the lot fee) in a while.” Eckhart returns about 30 minutes later, his truck lurching and screeching to a stop in front of his trailer. When he sees his belongings — a cuckoo clock he got while working as a contractor for the military, a new front-load washer and dryer, a four-post bed — outside in a mound, he boils. “This is fucking wrong!” he shouts. “They shouldn’t be able to go in there and look at all my shit! This trailer does not belong to them!”

Carolyn Carter, deputy director at the National Consumer Law Center, says trailer parks are thorny terrain when it comes to evictions because, like Eckhart, the people being set-out often own their home. And it’s relatively common, Carter says, for trailer parks to obtain the titles to trailers that have been left behind due to eviction and then lease them out. “The underlying fundamental imbalance is that, while it’s a horrible thing for an apartment tenant to be evicted, they can move most of their personal property, while a manufactured-home community resident often loses their home that they own.” (Some states have strengthened protections for trailer-park residents, restricting grounds for evictions, but Kentucky’s protections are weak.)

Later, Eckhart will admit his outburst wasn’t wise. But in the moment, he was sure he’d lose everything. His 25-year-old trailer would be too costly to move and many trailer parks won’t even accept older manufactured homes. “It’s just a kick in the nuts, speaking frankly,” he says later. In the weeks following the eviction, Eckart manages to sell his trailer home to a young couple. And he eventually winds up living at his girlfriend’s home. But for a few nights right after the eviction, with no place to go, he slept in his truck.

On a warm spring morning, two sheriff SUVs park in front of a cluster of brick apartment buildings in south Louisville. The renter, a young African-American woman, hastily piles bins and bags into her friend’s bronze Chevy sedan. The woman scowls. Not a word for the deputies who walk through her open front door.

The landlord, Broadway Management, is a frequent evictor, with a seasoned crew of five men who pull belongings curbside. (Deputies don’t touch property. It’s up to landlords to provide a crew and someone who can change the locks. Deputies keep the peace.) One of the crewmembers steps in the cluttered apartment. “You knew we were coming,” he says, slightly exasperated, to the renter. More hauling work for him and the crew. The woman doesn’t respond and soon disappears with her friend.

Garbage bags flap open, clothes and high heels are tossed in. A couch, then a bed, get carried out. A framed Marilyn Monroe print travels outdoors. Drawers are thrown from a dresser onto the floor. “Hey, take it easy!” a deputy calls to the crew. An LG&E bill and eviction paperwork sit on a high-top kitchen table that will soon vanish from its corner and join furnishings under the sun. Two men watch across the street from a stoop. One woman pops her head from a window with green shutters. “It’s always a show,” one of the men in the crew says.

Deputy Linsey Ongoy, a compact Hawaii native, has been on eviction duty for nine years. He’s easygoing and warm, often delivering moments of reflection. A few months before today, he stood in an apartment in Dosker Manor, a 685-unit public-housing complex stacked into three, well-worn towers just east of downtown. A man on the set-out crew wore what looked like a white hazmat suit to protect against bed bugs. Roaches also emerged as contents exited. Some fled for cover. One hung above a doorframe, watching the show.

Ongoy entered an apartment with a mattress on the floor, pictures of kids tacked to a corkboard, a white plastic chair and a radio playing soothing R&B. “This is all they had. It’s just sad. Not to say anything bad, but it makes you glad you listened to your parents,” Ongoy says, then pauses. “But some people don’t have choices.” Outside the apartment, pigeons swooped from one tower to the next in a synchronized arc. Someone in the crew hollered to a supervisor standing on a terrace a few floors below: “Carlos! We need a key!” On to the next place.

On this day, at the South Louisville apartment, Ongoy surveys belongings scattered on the light-brown carpet. Shot glasses tumble from a coffee table. “A lot of people are concerned with parties, not taking life seriously,” he says. “Rent comes up and they say, ‘Eh, next paycheck.’ They don’t realize they’re not supposed to pay late. It’s just sad. Especially couples with kids.” A member of the moving crew echoes Ongoy: “Especially when its kids, man.” In less than 30 minutes, the apartment feels deflated, a disappearing act but for trash and knickknacks.

Next, a high-ceilinged shotgun house on Bank Street in the Portland neighborhood. Ongoy recognizes the house as they walk through hip-high grass and weeds to the front door. He’s been here to hang eviction papers before. But the tenants and landlord always seem to work it out. This is the first time he’s been here for a set-out. “This is a real nice place,” he says. Across the street is Da’Marrion Fleming’s old apartment, the one he got evicted from in March. Draw a line a few blocks to the south, and this area surrounding the Bank Street home is made up of mostly rental homes — 70 percent. The eviction rate is 7 percent, higher than Louisville as a whole. And while median property value is low, about $32,000, median rent is not — $815.

“Sheriff’s office!” Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang. A man on the moving crew jostles keys and opens the door. No one is here, but the home reveals a history. A copy of the book A Purpose Driven Life remains. Mouse droppings dot furniture. Drawers contain two pacifiers, some pre-school flash cards and a birthday candle for a five-year-old. An open closet holds My Little Pony wrapping paper. As a drill grinds, changing the front locks, Ongoy slowly shakes his head. “Some people just live beyond their means,” he says.

Garbage bags flap open, clothes and high heels are tossed in. A couch, then a bed, get carried out. A framed Marilyn Monroe print travels outdoors. Drawers are thrown from a dresser onto the floor.

At the end of March, Dixon sits in her father-in-law’s modest brick house near Churchill Downs. This is home for now. He’s in a nursing facility, so she, her husband and three boys — 17, 15 and 12 — moved in. The walls are shaded a fuzzy yellow, stained from years of cigarette smoke. Seven white cats left behind by her father-in-law scramble at her feet. The runt scratches a worn white leather couch. “I’m 34,” Dixon says, showing a bandage that covers a trail of staples in her abdomen. “Too young for all these health problems.” She says that shortly after her day in eviction court, her appendix burst and a hernia needed mending. “Maybe it’s the stress,” she says.

In a nearby bedroom, the family’s brown-and-white Chihuahua yaps and the two oldest boys play video games. Both are suspended from school for cursing at a teacher and misbehaving. “Everyone’s falling apart,” she says, tears in her eyes. She contacted their school to explain that, perhaps, her boys’ attitudes may stem from difficult changes at home. Even her 12-year-old seems down. He misses his best friend at the old apartment complex and lately holes himself up.

Dixon has filled out apartment applications, but so far no one has contacted her. In addition to her evictions, Dixon and her husband filed for bankruptcy several years ago. One house she’ll tour — a cute four-bedroom, one-bath bungalow with almond walls and a cotton-candy-pink bathroom — is $950, plus a $950 deposit. “I’ll get the money,” she says, undeterred. She says the temp-agency job at the apartment complex pays her $14 an hour. Early on Saturday mornings, Dixon canvasses yard sales for designer clothes and video games, selling them at flea markets and on Craigslist. (“Look at these Calvin Kleins!” she’ll rejoice one day, pulling up a pant leg to reveal shiny beige pumps. “Five dollars!”) Dixon will work as event staff at Churchill Downs on Derby weekend. Still in a wheelchair from her surgery, she’ll complete the required training, her husband rolling her around. “Don’t worry,” she’ll tell her supervisors. “I’ll be fine by Derby.”

From six in the morning until eight at night on Oaks and Derby, she will direct folks to security-check lines, hollering through a megaphone. She will pocket a few extra dollars taking pictures for people. “They were paying me a dollar or two to take their pictures in front of the freakin’ Twin Spires,” she’ll recall with a laugh. “I was almost going to turn in my (event staff) vest and just do that.” She’ll endure a tomato-red sunburn on her forearms and face on Oaks, with Derby Day’s downpour actually feeling nice, “cooling” on her scorched skin. She will earn about $300 for the weekend’s work.

By the end of May, though, Dixon will separate from her husband. Problems in their marriage hardened after the eviction. Fights became habitual, and she needed a break. Shelters will be full. Her mom’s place too cramped. She doesn’t have a deep roster of relatives and friends. So she and the boys will pack clothes, shoes and gaming consoles into garbage bags and laundry baskets. It’s Memorial Day weekend. With few options, she will start looking into motels and pay-by-the-week hotels.

Judges Williams and McLaughlin know the rhythm of eviction court. They know to start late if it’s a snow day or traffic is bad, like the day of Muhammad Ali’s procession and funeral. It’s a small gesture that helps avoid default judgments against tenants running late. They know which landlords play dirty. They pick up on trends. One day, when a cabbie stands before her, McLaughlin pauses, tilts her head. “I’ve seen a lot of taxi drivers in here lately. It’s rough out there,” she says, alluding to the popularity of Uber and Lyft. (McLaughlin can roll a bit unfiltered at times, once telling a mother of five kids, whose boyfriend was living at her Section 8 home even though he wasn’t on the lease, “If you have five kids you need a husband who has a job.” The property manager evicting the woman clapped from the pews.)

Could the court be improved? Sure, Williams says. More legal assistance for poor tenants, like what occurs in bigger cities, sounds beneficial. But, she wonders: Where would the money come from? Not surprisingly, some lawyers grimace at the idea of bogging down the system with drawn-out landlord-tenant hearings. Maybe Louisville should look for ways to improve emergency assistance, but, Williams says, “We’re doing the best with the resources we have in Louisville.”

Over the phone on a recent afternoon, Williams reflects on her time in eviction court. She says she’s “a bit sad.” Come June, her time in that court ends. New judges will rotate in. Williams will hop over to criminal court. (Another change: After 30-plus years of holding eviction court in the morning, court is now midday.) Williams says she’ll miss her old post. “I feel like in eviction court, it’s a sad court, but what I appreciated about it was my ability to help people. I’m not trying to screw over anybody. I feel like when I was able to get two sides to talk, a lot of times it does work. I love that dismissed stamp.”

On a stormy May afternoon, sitting at a long conference table, Gabe Fritz, director of the Office of Housing and Community Development, says that when the Eviction Lab data was released, the issue leapt “on our radar.” Fritz, who has a gentle, thoughtful voice, proposes zooming out, looking at what the city’s doing to help poor renters from a wide angle.

He points to commitments the city has made to affordable housing, like more than $12 million allocated to the Louisville Affordable Housing Trust Fund, as well as $10 million budgeted for this coming fiscal year. (The LAHTF lacks a dedicated source of revenue and is trying to secure one.) Nearly $17 million has been given to other affordable-housing organizations in the last three years. A housing-needs assessment being conducted this summer will gauge how high rents have climbed and pinpoint neighborhoods in need of quality low-income housing. Fritz also reports that the city may help expand a rental-readiness program that the Louisville Urban League offers.

Some cities, particularly in New York and California, have aggressively chased ways to protect renters, adopting rent-control laws or legislation that requires landlords to pay relocation fees. Dial up a landlord in California trying to kick out a tenant in the Bay Area and the topic will likely elicit reactions ranging from genuine frustration to passionate rant. Certainly such laws don’t guarantee that a renter who wants to stay put will stay housed indefinitely. Plenty of landlords know how to skirt the rules.

They are business people. This is America. If landlords can get $900 for an $800 apartment, why not? Sitting across from Fritz at a conference table is Kendall Boyd, director of the city’s Human Relations Commission. He says rent-control laws have a “mixed bag of success.” And that controlling a private contract between two people can stir outrage. “Cries of socialism,” he says. Boyd believes in the mission of education, deconstructing the stigma of affordable housing, making landlords understand that folks who make $12 an hour need a decent place to live too. Not an easy sell. Just last year, Prospect residents protested a 198-unit affordable-housing project for seniors proposed by Chris Dischinger of LDG Development. In October, Metro Council denied a rezoning request. (A lawsuit is pending and federal civil rights investigators are looking into Metro Council’s decision.)

One particular area of Louisville with hundreds of renters and a high eviction rate has Cathy Hinko, director of the Metropolitan Housing Coalition, especially concerned. It’s that north-central section of Russell, with an eviction rate of 8.5 percent. Nearly 700 people live there, 219 of them children. A “ring” of investment projects surrounds these households, Hinko says. A $30-million neighborhood revitalization is planned for the Beecher Terrace public-housing complex and Russell. A new YMCA is slated to open next year, not to mention a proposed track-and-field facility to the west.

Hinko applauds investment and progress. But she’s nervous rent will climb, evictions too. Already 46 percent of renters in this area are cost-burdened. Fritz says avoiding gentrification of Russell is a priority among city leaders. “We are absolutely having those conversations,” he says, adding that people who live in Russell now should have “the ability to stay there should they so choose.” Fritz says he’s reviewing tools used in other cities, like tax moratoriums on affordable-housing properties. But Hinko wants more urgency and action before investors start scooping up property in hopes of a profit. “What is the damn plan for these 700 people?” she wonders.

On Derby weekend, Fleming packs up and leaves his mom’s house. His aunts help him move, requesting Beyoncé on the stereo as they unload his belongings at a three-bedroom house in the Park DuValle neighborhood. A family friend agreed to rent it to Fleming at $638 per month. After a year, he will have the option to buy. On a warm May afternoon, he picks up Josiah from school and heads inside to a cozy family room that sits off the kitchen. “This was an addition,” he explains, patting the wall, proudly giving a tour. There’s math homework on the kitchen table, Fleming’s weights in the basement, bags of books in Josiah’s room.

“Josiah’s at home,” Fleming says, smiling. “He tells people his home has a garage.” Josiah, quiet and polite, heads upstairs to read and change for baseball practice. Fleming feels blessed to have gone from eviction court to potential homeowner in a few months. At one point, someone advised him to go to a homeless shelter so he could secure emergency transitional housing or public housing. But Fleming couldn’t do it. “That’s not how I want my son to grow up,” he says. His options were few because landlords were avoiding renting to him. He felt like he’d never escape those past evictions.

Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, an eviction can stay on a tenant screening report for seven years. Some screening companies pay to obtain access to housing records digitally. In Jefferson County, one of the country’s largest data companies, LexisNexis, pays a woman to go to the Hall of Justice once a week. The friendly brunette sits at a long wooden table in the small-claims clerk’s office, scanning eviction and small-claims cases for hours at a time. Data companies collect and store housing records from nearly every jurisdiction in the country, marketing it to people like landlords.

James Fishman, a prominent New York consumer-rights lawyer, has been involved in several efforts to make the tenant screening process more fair. One push includes enhancing the reports; for example, instead of just showing that a landlord has sued a tenant, include information about the outcome, even details of the case. The current process can leave a renter blackballed. “There’s no dispute that there are certain people who are problem tenants,” Fishman says. “But this catches everybody in the net. They catch all the dolphins when they’re looking for tuna.”

On the eve of the last day of school, Dixon and her three sons settle into their hotel room in Okolona. Micah, the oldest, sits cross-legged on the floor and opens an aqua-colored box full of acrylic paints and paintbrushes. He selects a chestnut-brown paint and begins dabbing at an Andy Warhol-inspired mask project. The 15-year-old dives into his phone, and the 12-year-old plops in bed, pulling the yellow blanket over his head so he’s fully cocooned. “You tired?” Dixon asks. She sits at the small table sandwiched between the bed and the fridge. One of her son’s best friends searches for gaming videos to watch. “The hotel has free Wi-Fi, so that’s nice,” Dixon says. For a few days now, she and her boys have been living in the small room that costs $354 per week, a rate Dixon can only afford thanks to some help from her mother.

With one full-size bed and a twin-size pull-out loveseat, the family jigsaws at night: Dixon and her youngest lie next to each other on the bed, Micah sleeping horizontally at the end. Dixon’s middle son sleeps on the pull-out. Sheets are in storage at the moment, so last night she draped clothes over the twin mattress to cover stains. “We’re used to uncomfortable situations,” Micah says with a shrug.

Separating from her husband complicated Dixon’s financial situation, especially because she no longer has the temp job as a leasing agent. Had the eviction never happened, Dixon believes her situation would be “a lot more stable.” Micah nods, saying that the three-bedroom apartment they had was “perfect for us.”

This summer will be tight. Her mom can’t afford the hotel for more than a couple weeks. But Dixon is determined, resourceful. Yesterday, she pawned gold hoop earrings to help buy bread, deli meat, cheese and other groceries for dinner. She’ll try to find low-cost activities for the kids. “I got a flier at their school about summer camps,” she says, causing her 12-year-old to shoot a disapproving look. Micah’s a regular at free Sundays at the Speed Art Museum, and Dixon’s nudging him toward a summer job. She has posted a Craigslist ad as a house cleaner and is applying for more jobs as a leasing agent. The thought of an associate degree in business management floats in and out, if she can find tuition help. “I’m just taking it day by day,” she says. Perhaps she’ll reunite with her husband.

Tonight, leftover sandwiches for dinner. In a few days, Dixon should get one of her last paychecks from the leasing agent job. She’s trying to keep herself busy by helping friends with chores, tidying up her car. When she’s offered a cleaning job in Bullitt County, she eagerly takes it, earning $100. Anything to fill the space between now and what’s next. Because what’s next is unknown. And that’s exhausting.

A stroke of luck, she’d welcome that. Dixon picks up every abandoned penny, no matter heads or tails. To her, they’re worth more than a measly cent. That IN GOD WE TRUST hovering over Lincoln’s head? “It’s a sign someone is watching out for me,” Dixon says. “I don’t know who it is, but someone is.”

This article was originally published in print in July 2018. Marshall did some updated reporting on this issue last year. Read here.

Share This Article

We want to hear from you. Who or what should more Louisvillians know about? Share here.