What does it mean to be a Black LMPD officer?

This story, published in print in December, was reported at a time when LMPD veteran Yvette Gentry had returned from retirement to serve as what she called “chief for a while,” after Steve Conrad was fired from the position June 1 and his successor, Robert Schroeder, retired Oct. 1. On Jan. 6, mayor Greg Fischer announced that former Atlanta police chief Erika Shields would lead the force beginning Jan. 19. The appointment of Shields, who resigned from her post in Atlanta following the June 12, 2020, fatal police shooting of Rayshard Brooks at a Wendy’s, quickly sparked backlash. Some in the community felt betrayed by what they saw as a tone-deaf decision to hire a white police chief tied to a high-profile police killing of a Black man, at a time when the city was still deeply wounded by the death of Breonna Taylor. Meanwhile, the city’s powerful police union has pushed back against Shields’s belief that there are racial disparities in policing. The issues facing LMPD described in this piece will continue to face the organization as Shields takes over.

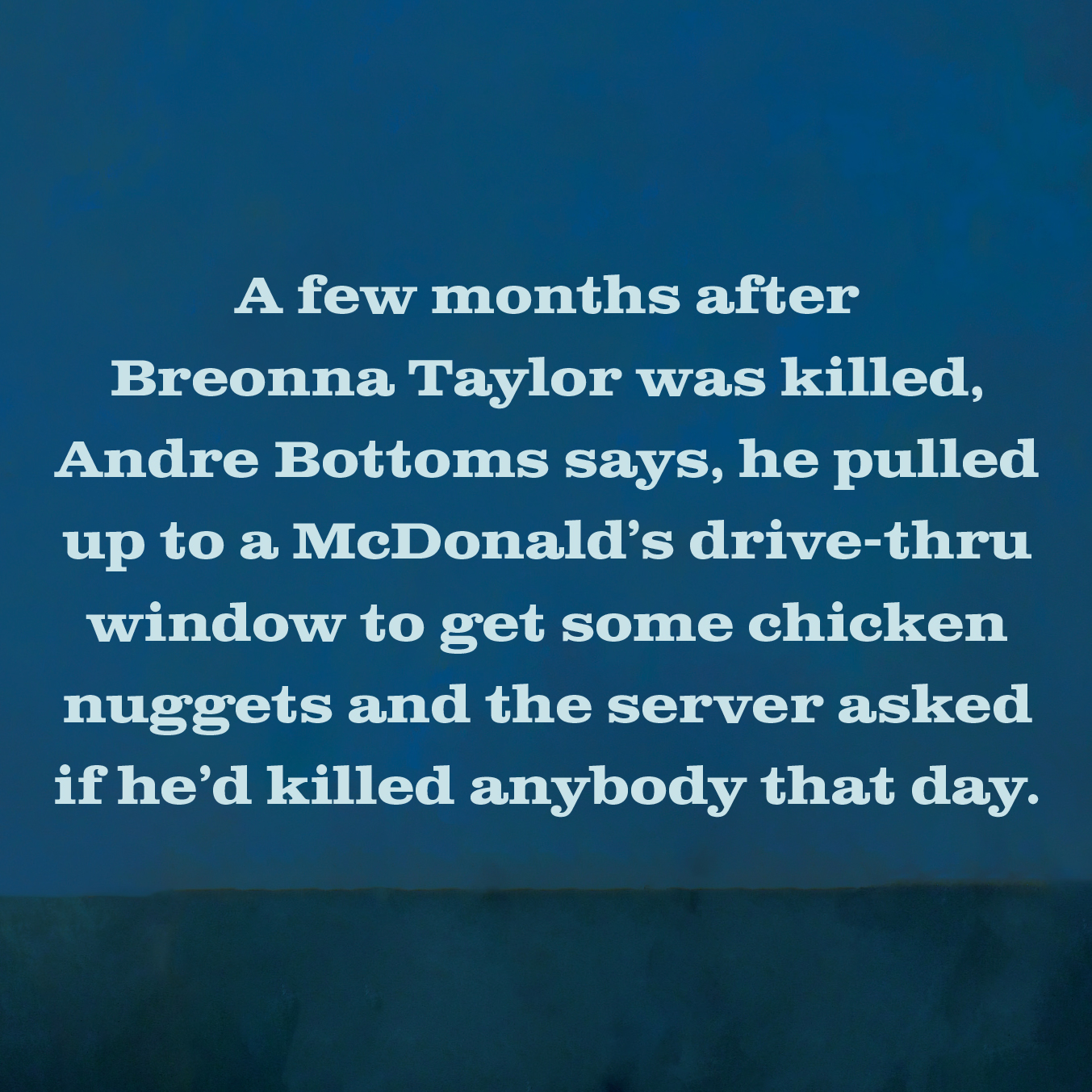

Christian Lewis was driving his pregnant girlfriend to a doctor’s appointment in Lexington when the flashing blues lit up behind him. He’d taken time off work to make the trek from Bowling Green, and his Freddy’s Frozen Custard & Steakburgers uniform smelled like grease. It was 2016, some time after Lewis first saw the viral video of a Black man named Philando Castile dying behind his Oldsmobile’s steering wheel after a Minnesota police officer shot the 32-year-old during a traffic stop for a busted taillight. “It really put me in a deep hole,” Lewis says of Castile’s killing. “I stopped wanting to go to school. It made me think: If that can happen to him, what’s to stop it happening to me?”

Now he was being pulled over. Lewis was a 23-year-old Black man driving an old Dodge Intrepid north on I-65 out of Bowling Green, where he was studying exercise science and gerontology at Western Kentucky University. He says he’d gotten into the fast lane to pass a car and then returned to the middle lane, and that he was going the speed limit and wasn’t breaking any traffic laws. After he made the pass, a police cruiser pulled up even with him, and the officer made eye contact before dropping back and turning on the flashers.

As the officer walked up, Lewis’s girlfriend was looking through her purse trying to fish out her ID. Lewis says the officer pulled out his gun as he approached; when the couple raised their hands, he holstered the weapon. After having Lewis get out of the car and asking him if he had any drugs or guns on him, the officer motioned to Lewis’s girlfriend and asked, “What’s up with her? She’s a little bit frigid.”

“I’m like, ‘We’re just scared of dealing with police,’” Lewis says. “We haven’t had a great interaction with police in historical lenses.”

The cop let Lewis off with a warning. To Lewis, it had nothing to do with traffic violations or safe driving. It was an incident of racial profiling, driving while Black — the kind of potentially deadly interaction Black parents warn their children about when they come of age.

That episode, combined with the killing of Castile, made Lewis want to change the world around him. “The two things that came to my head was a politician or a police officer,” says Lewis, who graduated from WKU in 2018. “I didn’t really know where to start trying to be a politician, so being a police officer is the easiest and quicker way to effect change in a community.”

If he were not an LMPD officer, Lewis would’ve been in the streets protesting.

His little brother was out there. So was his cousin, who is behind some of those 502 shirts with the power fist replacing the zero. Lewis has one of those shirts.

Lewis, now 27, lives in the same part of south Louisville where a 26-year-old Black woman named Breonna Taylor was killed in a hail of bullets fired by LMPD officers on March 13. It feels similar to Taylor’s Springfield Drive complex — affordable rents in a more rural edge of the city, a place for young people to live economically, work hard and plan the next steps in their lives.

Lewis didn’t think too much of it when, he says, he received an email about the officer-involved shooting after Taylor’s death. (In response to a request for the contents of that email, LMPD responded: “There is no procedure/standard email that is sent out.”) The address stood out to Lewis because of how close it was to his home, but that was about it. Officer-involved shootings happen with relative regularity, and 2019 had 16 such instances, four of them fatal. By the time this story went to press in mid-December, 2020 had seen nine officer-involved shootings, five of them fatal. Back when LMPD first announced Taylor’s death to the public, she was spoken of as a suspect, and her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, was facing a charge of attempted murder of a police officer for firing a shot from his 9mm pistol as officers breached the front door while executing a search warrant.

It wasn’t until after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25 that Lewis started to see Taylor’s name elevated, as the story surrounding her death became murkier. Soon, downtown Louisville was engulfed in protests. LMPD responded quickly and with a heavy hand, soaking downtown Louisville in tear gas and pelting protesters with pepper balls and baton rounds. There were incidents of violence and vandalism on the part of protesters, but at times police appeared to attack unprovoked, driving even more anger. Mayor Greg Fischer declared a curfew, and the National Guard moved in. As the anger spilled into the streets and business owners and government agencies boarded up windows, Lewis found himself having conversations about race with fellow officers. “Sometimes they don’t understand why people are so upset,” he says. “But it’s not just a death to us. A lot of people see themselves in her.”

Lewis tells other officers this analogy: Imagine a kid who has been bullied by another child from pre-K all the way through high school. It’s senior year and he’s sitting in class by the garbage can. The bully balls up a piece of paper and takes a jump shot at the can while yelling, “Kobe!” But it misses and hits the kid — the constant victim of the bully — right in the face. In this instance, the bully didn’t mean to hit him, but it happened all the same. Maybe that’s the kid’s breaking point, where enough is enough, no matter the bully’s intent.

While Lewis handled long, tense days on the force, his cousin, Isaiah Jones, attended demonstrations and distributed T-shirts. Jones, who is 28, crashed at Lewis’s apartment over the summer, relocating from his home in northern Kentucky to help with protest efforts. Back when they were kids in the West End, they were always hanging out. Nearly a decade ago, Lewis introduced Jones to David “YaYa” McAtee’s barbecue in the Parkland/Russell area, which surprised Jones because he always thought he knew the streets better than Lewis.

“Them grilled pork chops, that’s some of the best in the city, man,” Lewis says.

“The ribs, man, they really fell off the bone, bro. They were so tender,” Jones recalls.

In the early moments of June 1, LMPD officers and National Guard troops moved into west Louisville to disperse crowds violating the citywide dusk-to-dawn curfew. McAtee, a neighborhood fixture, had been cooking and serving despite the curfew, shuttling between his oil-drum grills outside and his indoor kitchen at 26th Street and Broadway — more than two miles from the epicenter of the protests downtown at Sixth and Jefferson streets. At about 12:15 a.m., police arrived and began firing pepper balls at customers gathered outside, sending them scrambling into McAtee’s kitchen for safety. McAtee, who was inside at the time, pushed through the chaotic retreat, stepped out of the door and fired what appeared to be a warning shot in the air. (McAtee’s nephew Marvin, who became a homicide victim on the same block three months later, said his uncle never would have fired at police.) The act prompted a barrage of return gunfire, killing the 53-year-old chef. Later, the state said a National Guard soldier fired the shot that killed McAtee. There was no body camera footage of McAtee’s killing, even though that was the one demand the city had agreed to, promising just hours before that all officers on the street during protest duty were wearing and using cameras. Fischer subsequently announced the firing of LMPD Chief Steve Conrad, who had already announced he’d be retiring.

McAtee’s name joined Taylor’s on the lips of protesters, and his modest barbecue stand became a magnet to those calling for racial justice. Lewis’s first deployment on protest duty came later that day as crowds began gathering there. He was a teenager when he met McAtee, but he said he didn’t know it was his death that had inspired the protests until he saw the chef’s mother arrive. “I knew he was a great man, always willing, loving, always a good father figure to everybody,” Lewis says. “And then also knowing that he’s super pro-police. Anytime you come, if you’re in uniform, or even if you’re not, he’ll give you food, he’ll let you use the restroom, he’ll always look out for you because he always supported us officers having good intentions.”

While Lewis was upset about many of the same things protesters were, with a blue uniform and riot helmet on, he was on the other side of the line. He was the police. The people protesters are addressing when they shout:

No justice, no peace, fuck these racist-ass po-lice!

How do you spell murderers? L-M-P-D!

Onetwothreefourfivesixseveneightnineteneleven fuuuck twellllve!

That day at 26th and Broadway, one of the protesters was shouting with a megaphone about how he knew Lewis’s family and where he lived. He said Lewis should be on their side. Later that day, Lewis wrote a Facebook post alongside photos of him overwhelmed and crying at the scene:

I can’t even lie man, this past week has been tough for me and heavy on my heart. I’ve been in a tough place, being a Black Officer in these crazy times. Today, I had my breaking point. When I found out an OG lost his life early this morning. Mr. D was from my childhood, and someone who watched over me through out the years. Mr. D always looked out for me, fed me and always loved that I became a Black Officer of change. I know that I can say that all Black officers are in a tough spot right now. We’re damned if we speak up too much on social media, or damned for not enough.

“I wanted to be transparent with myself,” Lewis says of the post. “I treated that like it was therapy a little bit.”

Henry Woolfolk, Lewis’s friend from WKU and a West End native, says he’s always worried police officers might be out to harass Black people. During protests, when he’d see LMPD using tear gas, flash bangs and other munitions on crowds that appeared mild, Woolfolk says he felt annoyed and upset with Lewis for being part of the force, but that it was also reassuring for him that there were cops like Lewis out there. “If I hear the ‘fuck the police’ chant, I’m most likely joining in,” Woolfolk says. “But as far as me and Christian, he knows it’s not geared toward him, because he knows that he’s doing what he’s supposed to do.”

Lewis’s three-year-old son emulates him, flipping his backpack around so it looks like a vest. “He’s real into the police because he wants to be like his dad,” Lewis says. “He just thinks he’s the police.”

Lewis, the son of a preacher and a schoolteacher in the West End, has already started warning his son about the dangers of being young and Black, telling him he can’t do things like play outside with toy guns. “Knowing the stuff with Tamir Rice”— the 12-year-old carrying a toy gun who was shot and killed by a Cleveland officer in 2014 — “it’s one of those things that, even now, I’m like, ‘You can’t be doing that’ or ‘You can’t do this.’ Even now, at the age of three, I’m still having some of these types of conversations with my son.

“When you’re young…you think everybody had that same conversation,” he says. “Until you go to these schools, which are very integrated, and you talk to other people and they weren’t brought up that way.”

After McAtee was killed, Jones says Lewis returned home drained and emotional. He sat on the balcony and talked for hours about McAtee’s death and the struggles of having an identity torn between the police and the community. “At the end of the day, he’s Black, but at the same time, he’s an officer,” Jones says. “So trying to maintain both of those…gets hard. You want to feel for the African-Americans because you are one, and it’s in your blood. At the same time, what pays your bills? What puts food on your family’s table? The clothes on your back? Shoes on his son?

“He’s a police officer because he just wants to make a difference,” Jones says. “He wants to bridge that gap. If we had more African-American officers, maybe things wouldn’t be the way they are.”

Getting sworn in at the Iroquois Amphitheater last year, Lewis became one of the most recent Black officers to join Louisville’s police force — an institution that dates to 1806, when five officers, or “watchmen,” were appointed.

More than a century later, in 1922, the department hired its first Black officer, Bertha Whedbee, less than a year after hiring its first white woman. According to the Encyclopedia of Louisville, women officers were limited to “patrolling dance halls, apprehending thieves in downtown department stores, working with children and performing female body searches.” (After Whedbee’s death in 1960, she was buried in an unmarked grave, though she finally received a tombstone in 2018 after a fundraising campaign led by a former LMPD officer.)

A year after Whedbee’s hire, Page Hemphill and William Woods became the first Black men to join the force. “Negro Detectives Will Be Appointed” announced the headline buried at the bottom of page three in the Courier-Journal. “The two negroes will be assigned to work among the negroes and will be in plain clothes, it is understood,” read one of the article’s three sentences.

A decade after joining the force, Woods was gunned down a few days before Thanksgiving 1933 while sitting in his unmarked police vehicle on Seventh Street, near where the Greyhound station is today. “White Man Kills Negro Cop, Escapes,” read the front-page headline in the C-J the next day. A higher-ranking officer described Woods as “one of the best liked men in the department — a pacifier instead of a bull-dozer.” The shooter was a 27-year-old white man who was sentenced to life in prison but was released nine years later.

In response to a lawsuit over discriminatory hiring practices, a 1979 federal consent decree mandated that the Louisville Police Department consist of 15 percent African-American officers. The force met that requirement a decade later and halted its practice of hiring one Black officer for every two white officers. Currently, the 1,105-officer Louisville Metro Police Department, named such with the city-county merger in 2003, is about 13 percent Black, while Louisville’s population is more than 23 percent Black. Through October 2020, 45 percent of adults arrested in Louisville were Black, according to LMPD statistics.

Some of these disparities have seen LMPD take heat, and have prompted policy changes in the city, such as Jefferson County Attorney Mike O’Connell announcing that possession charges for small amounts of marijuana would no longer be prosecuted and changes to how traffic stops are conducted.

The police killing of Breonna Taylor in March, an incident in which three white LMPD officers fired 32 bullets into her apartment after her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, fired a single shot, has put Louisville’s police under the microscope. A spokesperson for the Louisville Metro Corrections union called Walker — a licensed gun owner who claims he didn’t know it was the police busting down the door — an “attempted cop killer” when he was released from jail in March. Ryan Nichols, the head of the city’s police union, called Walker’s release a “slap in the face to everyone wearing a badge.” The LMPD incident/investigations report about that March night listed Taylor’s injuries as: “None.” The only photos of Taylor scraped from Walker’s phone that the LMPD Public Integrity Unit included in its report showed her posing with firearms — a head-scratching move in a gun-loving state like Kentucky, where guns are so common and accepted that LMPD once posted cutesy messages on social media reminding gun owners to make sure they took their “pew pews” out of their cars before turning in for the night.

In the early days of the protests, LMPD put together a video montage of looting and property damage that exclusively featured Black people, even though the majority of protestors — Black and white — were nondestructive and white folks were also culpable of vandalism.

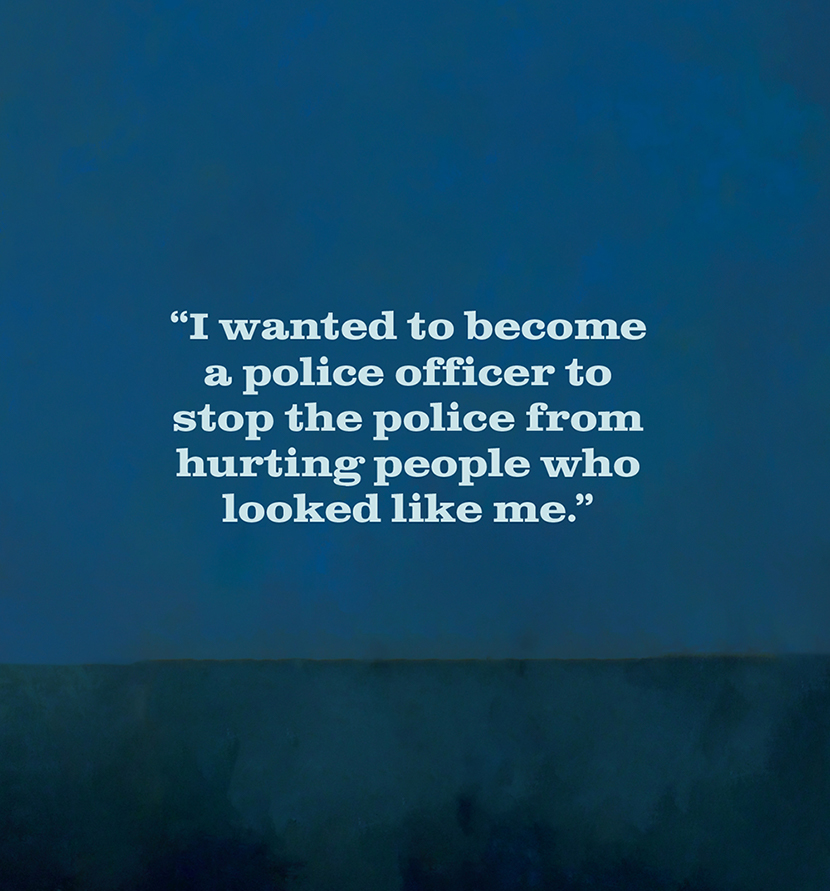

Steven Kelsey, who is Black and retired from LMPD in 2014, wonders what things would have looked like if the races in the Breonna Taylor killing had been reversed. “Instead of her being Breonna, what if she had been Britney? Black officers shot Britney. It would have been a whole different narrative,” Kelsey says.

Andre Bottoms spent more than a quarter-century and about half his life on the force, already coming out of retirement once in 2016. This year changed things for the 53-year-old. “I actually planned on staying longer, but I just couldn’t take it anymore,” he says. “With everything that was going on, I felt there was a lack of leadership, and the leadership did not have the best interest of the officers.”

Opaqueness and silence from LMPD amid rumors about the circumstance of Taylor’s death — that she was sleeping in her bed when police shot her, that officers had shown up at the wrong address — took emotions in the city to a higher level. Officers working the protests were putting in 12-hour shifts with no days off. Officers were overburdened and overstressed, putting them in a situation where costly mistakes could be easy to make. “If I was going to grade the police department, I would give them a D,” Bottoms says. “The shooting itself…was one side. But to allow rumors and not being transparent about certain information is something the police department had control of.”

In recent years, the department has been criticized for its lack of transparency. In November, adding to a years-long saga, the C-J reported that LMPD lied and withheld more than 700,000 files related to the sexual abuse of teens by LMPD officers in its Explorer program for youth interested in law enforcement. (The C-J reported that LMPD declined to comment on that development.) Metro Council President and former LMPD detective David James calls the department’s transparency “horrendous. They even have a transparency page (on their website), but the reality is that transparency page isn’t very transparent,” he says. “And the (Fischer) Administration is probably the least transparent I’ve ever seen.”

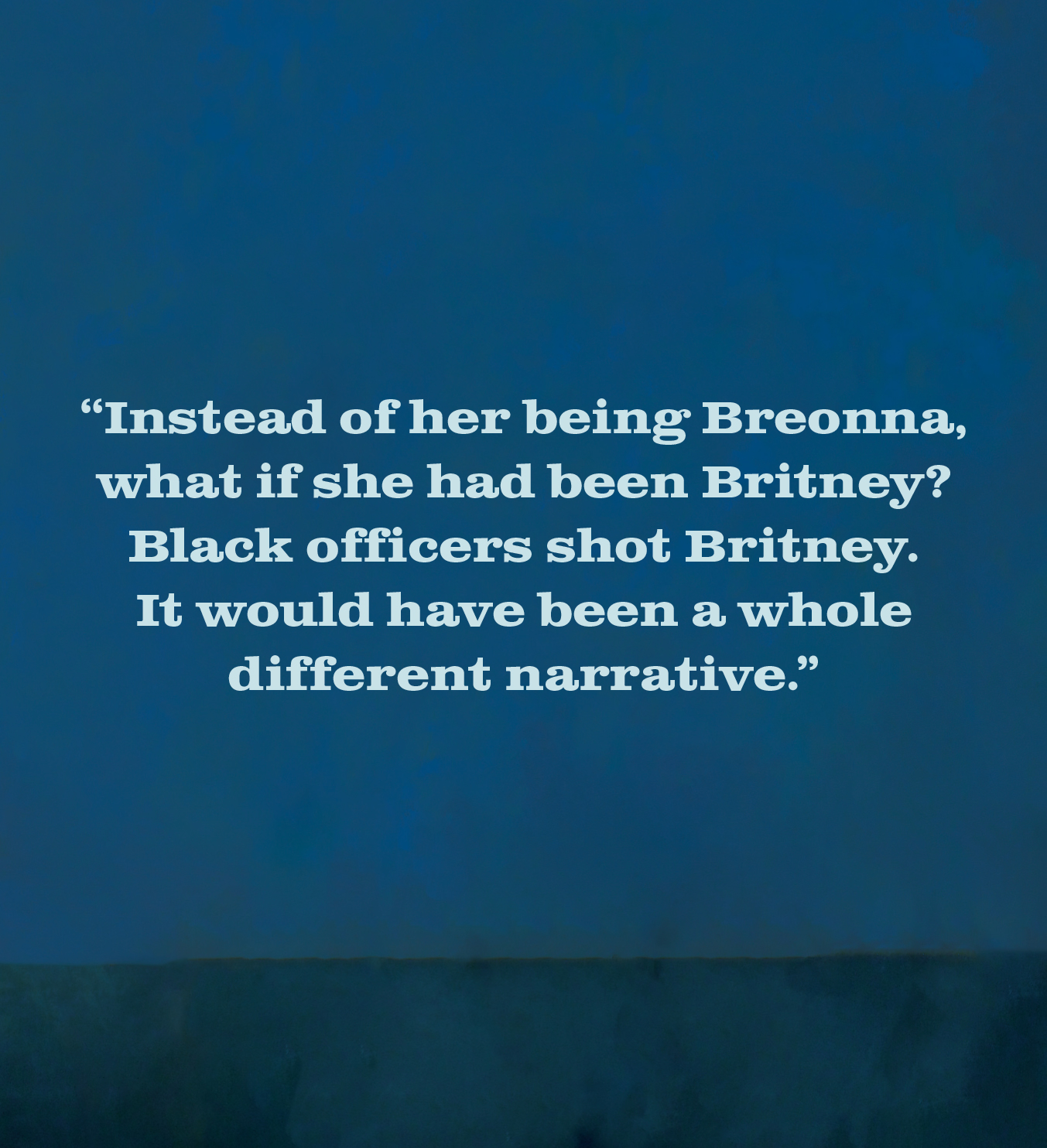

Bottoms says that a few months after Taylor was killed, he pulled up to a McDonald’s drive-thru window to get some chicken nuggets and the server asked if he’d killed anybody that day. Those kinds of statements are tough for Bottoms to hear because, as a Black man in Louisville, he has been racially profiled by police his whole life. Back when he was in high school, Bottoms was driving home from a trip to the Kings Island amusement park near Cincinnati when he stopped for snacks at about 11 p.m. near his home in Shively. His girlfriend, who was white, was asleep in his car as he went inside the store. When Bottoms emerged, he says, a Shively police cruiser had pulled up and the officer was talking to his girlfriend. Bottoms asked if he could help. The officer told him to shut up. “He called me ‘boy,’” Bottoms recalls. The cop was asking his girlfriend if Bottoms had done anything to her, or if she was there against her will. “To me, that whole incident had to do with race,” he says.

When Bottoms joined the Louisville Police Department several years later, he says one of his first runs was backing up the Shively officer who had harassed him. He asked him if he remembered him. He didn’t.

It was the actions of another officer at that same Shively convenience store years earlier that inspired Bottoms to become a police officer. Bottoms and his family had moved to Shively from west Louisville when he was in the first or second grade. They were the only Black family on their street — and the only Black family for two or three surrounding streets, he says. Kids in the neighborhood would call Bottoms the N-word, which sometimes led to fights. Bottoms would hang out with his younger brothers at the convenience store a block from his house, playing arcade games like Galaga, Pac-Man and Defender. An older white Shively officer was another frequent visitor to the store, stopping in to get something to drink during his shift and to chat with the owners. “He always made a point to come and talk with us,” Bottoms says. “It just seemed like he was interested in what we were doing, always telling us to make sure you don’t take the wrong path and make sure you make good grades in school. He was just a very nice guy.

“That always resonated with me,” he adds. “And I believe that was one of the major factors of me wanting to become an officer.”

After a stint in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve and a job at Circuit City, he joined the Louisville Police Department in 1991, right after a video tape of Los Angeles Police Department officers beating Rodney King had sparked anger across the country.

Bottoms has been shot at on the job, but he says “the closest I felt that I came to getting killed” was in 1993 when he drove to a friend’s apartment to pick up a CD. It was maybe 10 or 11 p.m., and Bottoms had pulled up at the Piccadilly Apartments off Hurstbourne Parkway and Bardstown Road in his teal T-top Camaro. He was wearing jeans with a T-shirt tucked over his gun.

As he was walking to the complex’s door, men in street clothes with guns drawn swarmed him. For a moment, he thought about pulling his gun. “When I got these guys running up on me, my first instinct is: I’m gonna get robbed,” he says. “But when they was yelling ‘Get on the ground!’ and ‘Show us your hands!’ — I knew they was officers at that point.”

After complying, Bottoms told the undercover officers that he, too, was police. They explained that they’d been watching for drug-activity suspects going into an apartment in the complex. But he saw flaws in that explanation: They couldn’t tell what apartment he or anybody else entering the building was going to, for one, and this was the first time he was visiting his friend’s apartment, so it wasn’t like he’d done anything to raise suspicions by coming to the building repeatedly. “That told me that anybody that was Black who pulled up at that apartment complex, in front of that building that they was watching, they was going to run up and draw down on and see if they had drugs,” he says. “And that’s not the proper way to conduct a narcotics investigation.”

Bottoms drove home that night with his arms shaking on the steering wheel. He realized if he had made a wrong move, he probably would have died. And if that had happened, the officers’ justification probably would have been that they feared for their lives. “That’s what officers always say: I was in fear for my life,” he says.

On Sept. 23, a grand jury announced that, of the three officers who fired their weapons the night Breonna Taylor was killed, Brett Hankison would be charged with a crime — wanton endangerment for shots that entered a neighboring apartment. In the streets, a stunned silence on that Wednesday afternoon exploded into a loud anger as protesters marched across the city. A Black woman was dead at the hands of police and the cop got charged for the shots that missed? Businesses were boarded up if they hadn’t been already. Barricades and LMPD checkpoints blocked off much of downtown. The National Guard patrolled Fourth Street Live.

That evening, as protesters marched at Brook Street and Broadway about half an hour ahead of curfew, police used flash bangs to try to disperse them. A man in the crowd unleashed a salvo of bullets from a handgun, hitting two officers. One of the cops hit was Robinson Desroches, a Black officer who came up through the training academy with Lewis. A member of the Special Response Team, which specializes in crowd control and has faced off with protesters countless times this year, Desroches has always sought to de-escalate situations, Lewis says.

“He would always ground people. He would always say, like, ‘You need to relax, you need to take a walk,’ or, ‘We can’t talk to people in that type of way,’” he says.

“When you ask the protesters: What type of officer do you want? He fits it to a T. To see him shot is tragic. And it was real tragic that it can happen to any of us, even if you are doing the right thing.”

Desroches was shot in the abdomen and was hospitalized for more than a week. A 26-year-old man was arrested and charged in the shooting, which also injured Maj. Aubrey Gregory.

Throughout Louisville’s months of unrest, Lewis has somehow not found himself on a police line that used force on protesters. “I’m glad I wasn’t,” he says.

“I tell my beat partner: If you’re out there on the line and you’re going to do something crazy, I know I will step to you, and I know some other officers that will, because we didn’t join just to be in the club. We joined to step up for what’s right.”

On January 1996, President Bill Clinton came to Louisville to promote community policing and to woo voters, in hopes of keeping the Bluegrass state blue in November. After a roundtable discussion with police officers at what was then the headquarters of the Louisville Police Department’s fourth division in Park DuValle, Clinton addressed a crowd of 1,400 people at Male High School. He was introduced by Steven Kelsey, who told the crowd that Clinton was “the man under the divine guidance of the almighty God, who will lead us into the next century.” The next day’s Courier-Journal featured a photo of a smiling Clinton embracing Kelsey.

Kelsey’s introduction at Male drew applause; what he said to Clinton at the precinct drew a different reaction. During the roundtable, Kelsey says the president asked him why he became a police officer. “I explained to him that I became a police officer because I wanted to treat people the way I wanted to be policed,” he says. He told Clinton about growing up Black in Newburg, and how he and people like him felt they had been harassed by police.

The next day he discovered an anonymous handwritten letter in his mailbox at work, saying Kelsey was arrogant, that nobody on the force liked him, and that he had taken advantage of the moment to glorify himself. The note said he wouldn’t receive backup when he requested it. It called him the N-word. “I just dealt with it, you know. I knew if there was internal racism and I was African-American, I could only imagine how they treated people in the community,” he says.

“I knew I had a greater calling. I knew I had a job to do. I lived in the West End. I patrolled in the West End as a Black man, and my commitment was to serve the people.”

Kelsey would go on to save the life of a two-year-old girl in 2006. She had been shot in the head, and he raced his cruiser at 80 miles per hour to get her to the hospital, while paramedics tried to keep her alive in the backseat. Kelsey retired in 2014. He is currently a therapist and a pastor at Spirit Filled New Life Church Ministries across from Iroquois Park. In September, he was named faith-based liaison to the city’s Office of Safe and Healthy Neighborhoods.

In the basement of his church, Kelsey’s office is crowded with books on criminology and psychology. Twenty-six-year-old barber Mark Pence wears a mask that reads BREONNA TAYLOR in glittering gold letters as he carefully shaves Kelsey’s head with a straight razor. Sculptures of Lady Liberty and Lady Justice look over the room from atop a cabinet behind Kelsey’s desk. He says those values have yet to be realized due to institutional and systemic racism. “Whether I’m a police officer or not, I’m a Black man and have a Black son, and I have to share with him the talk: That when you’re pulled over by the police, you give them respect, you keep your hands where they can see them,” Kelsey says. “Why does a traffic stop have to be homicidal for us?”

Pence chimes in as he trims Kelsey’s beard.

“That’s why I take off running, ’cause I don’t know if I’m going to die or not. I’d rather just take my chances running and getting shot in the back than trying to sit there and still get shot.”

Kelsey worries about his 22-year-old son and laments how that son can’t drive the Cadillac Escalade parked outside. “I have a Mercedes, a Jaguar and an Escalade. I can’t let him drive those because the perception is he’s a dope dealer and he’s going to get pulled over,” Kelsey says. “My son will be targeted. I’m targeted as a grown man.”

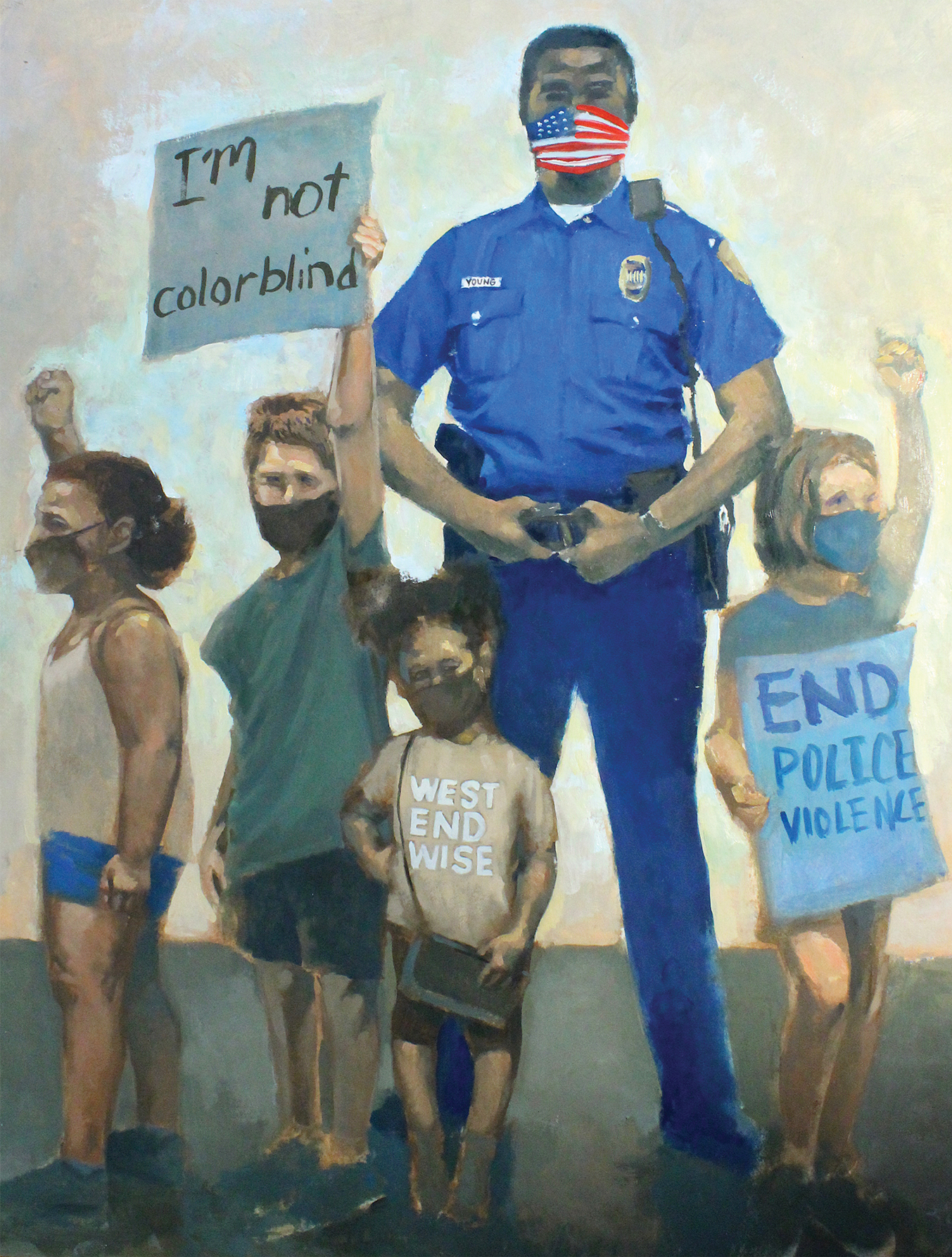

Kelsey isn’t alone in receiving racist abuse from other members of the force. Growing up in Chickasaw and Shively, David James, now president of the Metro Council, developed a “huge distaste” for police. He associated them with his neighbor’s broken arm during unrest in the ’60s and for smacking him in the face with a slapjack when he was 14, walking home from a football game in his Butler High School marching band uniform. “I wanted to become a police officer to stop the police from hurting people who looked like me,” James says. He says his parents “were not at all thrilled with that scenario.” (On Jan. 21, James said he will run for mayor of Louisville in the 2022 election. At the announcement, he brought up the slapjack incident saying, “I understand when people talk about when we have bad police officers that do bad things to people. I know firsthand.”)

On his first day on the force in 1984 — during the department’s diversity push at the time — James wore his uniform to what was then the sixth district in Portland. He realized that many other officers came to work in normal attire and kept their uniforms in lockers at the precinct. So on the second day, James decided to do just that. “When I went into the locker room, on my locker was a note calling me the N-word and (saying) that I needed to leave,” he says. “I didn’t tell anybody.”

The letters continued for two or three weeks, with later notes saying things like: Leave. We don’t want you here. You’re only here because you’re Black. You couldn’t pass the test. James retired from LMPD in 2003, and, in 2010, he was elected to Metro Council, representing the sixth district (which includes parts of Old Louisville, west Louisville, Smoketown and downtown).

Some incidents between officers have happened more recently.

In 2014, right before Bottoms retired from LMPD for the first time, he stopped at Thorntons on Cane Run Road in an unmarked police vehicle after leaving a court appearance. As he got out to pump gas, he was wearing a dress shirt and tie and had his pistol on his hip.

Bottoms looked over at an LMPD cruiser at a neighboring pump, trying to suss out if he knew the officer or not. Either way, he thought he’d strike up a conversation while his tank filled. But the other officer spoke first, putting his hand on his own sidearm.

“He sees my gun and he tells me: ‘You better have a badge to go with that,’” Bottoms says.

Bottoms says he told him that, first off, Kentuckians are allowed to open carry and don’t need to be a police officer to have a firearm. Then he pulled out his badge, which showed that he was a sergeant and outranked the officer.

“Now he’s all, ‘Sarge, I’m sorry, I apologize,’” Bottoms says. “I said, ‘It don’t matter that I’m police. I got a right as a citizen to have my gun and open carry. So why do I better have a badge? What were you going to do to me?”

Bottoms says the officer told him, “It wasn’t like that.”

“There’s no doubt in my mind that happened because I was Black,” he says. “There’s no doubt.”

The killing of Breonna Taylor and the protests that followed have resulted in a large number of reforms promised by the city and its police department. No-knock warrants — like the one that was obtained for Breonna Taylor’s apartment — have been banned. Officers are now required to wear body cameras while conducting search warrants (though enforcement of the use of those cameras has been another debate). Chief Conrad was fired. The statue of John B. Castleman, who served as a Confederate officer, was removed from the Cherokee Triangle. Interim Chief Robert Schroeder fired Hankison for recklessly discharging his weapon during the raid on Taylor’s apartment and for showing an “extreme indifference to the value of human life.” A new policy stipulated that officers must receive authorization from higher-ups before using tear gas during civil unrest.

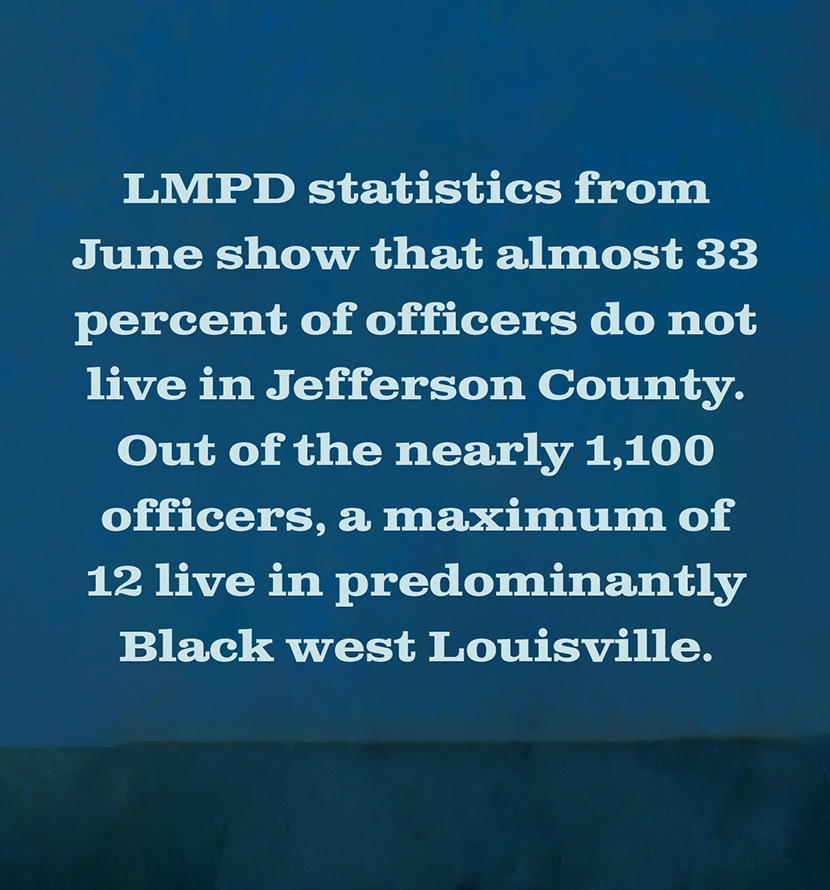

In September, the city paid Breonna Taylor’s estate a $12-million settlement, and Mayor Fischer announced plans for even more reforms: for social workers to respond to some 911 calls (regarding situations like substance abuse or mental-health emergencies); for incentives for police to live in the city; for an early-warning system that would identify potentially problematic officers; for encouraging officers to do community service where they work. LMPD statistics from June provided by Metro councilman Bill Hollander show that almost 33 percent of officers do not live in Jefferson County. Out of the nearly 1,100 LMPD officers, a maximum of 12 live in predominantly Black west Louisville. (LMPD declined a request for data on the ZIP codes of individual officers, citing privacy concerns.)

Despite reforms, the events of this year have “shattered” the relationship between LMPD and a community that was already distrustful of the organization, says Cherie Dawson-Edwards, the associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion at the University of Louisville. “And you can’t rebuild shattered glass,” she says. “You have to do something else. You have to do something different.”

Dawson-Edwards says her decision in September to leave her previous position as chair of the U of L criminal justice department was partially driven by the feeling she couldn’t openly comment on social-justice issues in Louisville while remaining in that role. She has worked closely with police throughout her career and says she has a strong knowledge of how police operate. But as a Black woman with a Black family, she says calling LMPD would be an “absolute last resort.

“I have two Black men in my house: my husband and my son. I’m not calling the police so they can come to my house not knowing who lives here and see two Black men,” she says. “It would have to be a serious, violent something happening for me to call the police in 2020 — for me to call LMPD. And if I feel like that and I live in the suburbs and I know a lot of police officers. I can’t imagine what other community members that look like me are feeling.”

Of the LMPD academy’s 1,050 hours of training for new recruits, a three-hour class is dedicated exclusively to biased law enforcement practices. Among other things, it covers the history of racism in America and the role law enforcement played during the civil rights movement. Implicit bias is also part of a two-hour class that discusses the “guardian mindset” and building trust. Separate seven-hour classes go over “respect for all people” and ethical behavior. Expandable baton training runs 14 hours. Firearm training is 141 hours. Seven hours is devoted to training on gangs, and four are dedicated to directing traffic.

Maj. Paul Humphrey, the commander of LMPD’s training academy, says the amount of time spent on things like firearms compared with implicit bias can draw criticism. But he says the trainings on use of force make officers more confident in their skills and less likely to make dangerous mistakes. “When it comes down to it, people who train more — whether that be mentally or physically — are more confident in their skills and their knowledge,” he says. “And when you’re more confident in your skills and your knowledge, you’re less likely to overreact. And I think some of the failures we’ve seen nationally are an overreaction based on lack of confidence in their skills.”

Dawson-Edwards, who taught criminal justice for 19 years, is pessimistic that reforms like more training about implicit bias will yield results without a more sweeping overhaul or reimagining of policing. “Reforming strategies have not worked for Black and brown folks in this city or in this country,” she says.

Humphrey says, “There’s a large segment of the population where we were never trusted. When I say ‘we,’ I don’t mean LMPD — I mean the police. That’s never existed. So it’s about building. It’s not about rebuilding; you can’t rebuild something that was never there.”

In June, former LMPD deputy chief Yvette Gentry sat down for an interview with the Frazier History Museum’s Rachel Platt. At one point, Platt asked her what she would like to see in the next chief. “I would love to see a female get an opportunity, and I would love to see an African-American get an opportunity,” she said. “The sad part in law enforcement is, typically, Black commanders only get an opportunity when things are really bad.”

In 2003, Mayor Jerry Abramson appointed Robert White, who is Black, as chief of the newly formed LMPD amid protests about awards given to officers who had shot and killed a Black teen. White left for Denver in 2011, but this summer, amid pressure from protesters, Mayor Fischer asked 68-year-old White if he would again fill the high-stakes opening. White declined.

In September, the city announced that Gentry would be taking over as interim police chief. (She has said she’s not interested in the permanent position.) Gentry, 50, would be the city’s first woman and first African-American woman to serve as chief. She served in LMPD for 14 years, rising to deputy chief before retiring in 2014. In 2015, she told Louisville Magazine, “There’s nowhere else for me to move upward in that police department.” Following her retirement from LMPD, she served as the executive director of the foundation created by Louisville native and basketball star Rajon Rondo, and as project director for Black male achievement at Metro United Way.

In a teary speech on the day her appointment was announced, Gentry spoke of how she didn’t just want to take the plywood boards off downtown buildings, but also the buildings of the West End where they had been up for decades. She said the hopelessness the city was feeling right then was just a glimpse of what many people had been feeling for a long time. And she talked about how her own son had been racially profiled and felt unwelcome in a city she had put her life on the line for.

Gentry is a sharp contrast to her predecessors, talking about experiencing the same feelings as many protesters. “I was upset, I was sad, I was angry,” she says of her reaction to Taylor’s death. She thought of the pain her mother would feel. “I felt every emotion you can imagine over the course of these few months, just like most people.

“I know that as a person who knows history, I realize as a Black woman, most of any rights we obtained came through peaceful protest. It wasn’t freely given,” she says. “It takes sometimes an outside influence to push the needle along.”

The main reason she didn’t actively participate in protests this summer was health concerns; she is a breast cancer survivor and avoids crowds, particularly during the pandemic. She points out that Metro United Way was a drop-off point for protester supplies while she was still working there.

Growing up in Smoketown, Gentry was around police from a young age. Her mom worked in the department’s dispatch center. Across the street, Gentry’s neighbor was a Black single mother who was a police officer. “She made it look like something worth doing,” Gentry says.

In high school, during a rebellious streak, she says, she ran away from home to go live with her aunt for her junior and senior years. “I wasn’t an abused child, I didn’t have terrible parents or whatever, but just wanting to do it on my own,” she says. Calling herself a “runaway,” she referenced that time in her life during a short speech on the day she was sworn in as chief.

“The reality is, there are so many kids who give up on themselves at 17 years old because of the decisions that they made when they were 15 or 16,” she says. “I just wanted to let them know I was you, and I still am you.”

When she took over as chief, one of her first orders was to take down the plywood boards on LMPD headquarters.

Speaking at Gentry’s swearing-in ceremony on October 1 at Metro Hall, Syracuse Police Chief and LMPD alum Kenton Buckner tempered expectations that the interim chief would solve the city’s problems. “You know that you’re handing her a turd. You know that. And I use that word intentionally,” he said. “Don’t expect her to give you back a patty melt in six months. Victory in some cases will be putting lettuce and tomato on that turd and stopping this boat from rocking. That’s victory.”

In September, the city surpassed its previous annual homicide record of 117 with more than three months to go in the year. As of December, more than 150 people had been killed, nearly all by guns.

On Oct. 12, less than two weeks after she took over as chief, Gentry headed down to Jefferson Square Park (now co-opted as Injustice Park or Breonna Square), across from Metro Hall. Some protesters had been playing basketball on a rim mounted to the back of a bus that was parked alongside the park. An altercation ensued when officers tried to clear them out and several were arrested. Gentry arrived when tensions were high, coming down to the square in her uniform without body armor and clutching a Kroger water bottle in her hand.

In a conversation captured by live-streamers, she appealed to the protesters, telling them that she needed to spend time working on big issues facing the city — like the skyrocketing murder rate and where homeless people were going to go when it’s too cold to sleep outside in a month.

“When my clock is ticking, I don’t want to be coming over here worrying about basketball rims when you can’t have a basketball rim in no park because of COVID right now,” she told them. “That’s just a battle that I ain’t got time to fight. People don’t have a roof over their heads.”

Joseph Grant, an assistant professor of criminal justice at U of L who previously was an instructor of ethics, interpersonal communication and defensive tactics at LMPD, has spent a total of 24 years in law enforcement. He says healing must precede any big police reforms. “Before any major, significant changes are done, you got to stop the bleeding,” he says. “We’re still bleeding from the incident. And that wound’s got to start to heal before we can start calming the waters to where we can sit down and talk. And I think (Gentry) will do that.”

It’s not difficult to imagine a culture clash at LMPD now that Gentry is chief.

In September, two department-wide emails denigrating protesters and written by officers were leaked to the press. In one from August, Maj. Bridget Hallahan wrote: “Our little pinky toenails have more character, morals and ethics, than these punks have in their entire body.” She added: “Don’t make them important, because they are not. They will be the ones washing our cars, cashing us out at the Walmart, or living in their parents’ basement playing COD (Call of Duty) for their entire life.”

One of the officers involved in Taylor’s shooting, Sgt. Jonathan Mattingly, who was hit in the leg by a shot fired by Kenneth Walker as the apartment’s door was breached, sent out a late-night department-wide email, calling protesters “thugs” as Louisville nervously awaited the grand-jury decision. “It’s sad how the good guys are demonized, and criminals are canonized,” he wrote.

The River City Fraternal Order of Police, the city’s powerful police union, called for the removal of banners honoring Breonna Taylor that had been hung up on light poles by the city. Two of the union’s members, both of whom were retired LMPD officers, were expelled for making racist Facebook posts related to Gentry’s hiring.

To Dawson-Edwards, the emails were deeply troubling and emblematic of a larger cultural problem at LMPD. “The fact that you think all the officers would have been OK with that message?” Dawson-Edwards says. “That speaks volumes to me about a culture. Because why would you think sending that out to a number of people — that that’s how everyone else feels?”

Bottoms says, “The police department is not at war with the citizens. And if you look at those emails that were sent out by those two, that’s what it looks like.

“I think it’s a noble profession. I think it’s one of the few things you can do to serve your city. I love the city of Louisville. I was born and raised here. I never wanted to live anywhere else. To this day, I’m proud to be an officer.”

Gentry suggests there is a small “subculture” of LMPD officers “who are negative and maybe just never should have been here,” adding, “We have got to get rid of some folk. And we have got to regain some discipline. And we have got to think about more of our practices and our standards.” She also says LMPD has to do a better job with transparency. “Sometimes people just flat out lie. Sometimes we have had a problem telling the truth,” she says.

Asked what they want to see LMPD look like in the future, several Black Louisvillians connected to the department came up with the same answer.

“I want to see a little more diversity,” Gentry says.

“I would say more inclusive,” Lewis says. “Having more Black officers and more Asian officers and more Hispanic officers.”

“Number one, I want the department to reflect the makeup of the community,” Bottoms says.

Mayor Fischer, whose third and final term is up in 2022, says a more representative police force has “always been a goal” and “continues to be a goal” of the city.

Data provided by LMPD going back six years show the least diverse pool of recruits in that time frame came in 2015, with 15 percent minority candidates. The latest pool of recruits was 40 percent minority members, up from 36 percent in the previous class. In November, Gentry said the force was 194 officers short of capacity. “I remember coming on and feeling lucky because I could get on the police department because we used to get thousands of applications,” she says. “Now we’re lucky to get a few hundred.” (A top-to-bottom review of LMPD that the city ordered from Chicago consulting firm Hillard Heintze was released Jan. 28, after this story appeared in print, and it recommended that diversification become a priority for the force. The firm found that “many LMPD personnel believe that Black officers have a distinct disadvantage when it comes to assimilating into what has become a white-dominated organizational structure. Department personnel perceive that significant inequities have prevented officers of color from succeeding in that Black officers have not been given the opportunity to achieve special assignments and promotions on par with those opportunities afforded to white officers.”)

According to Gentry, there are four Black women at the command level at LMPD, including herself. All are eligible for retirement. “We really need African-American police officers to join the police department and be the change that they want to see,” she says. “I just really want them to understand that we come from the same neighborhoods. I think there’s some perception that when you put on this uniform, you lose your life experience. We suffer the same things that everyone else suffers. We have the same challenges in our family that other people have. So when you put this uniform on, it’s not like you don’t understand what it’s like to live in this city and live in this world.”

Grant, the former LMPD instructor, says, “I don’t necessarily believe in that, where you’ve got X amount of people in the community who are Black, Asian, whatever, so you have to have that reflected in your police department. What I do go along with is this: You want the best officers on the street. Now, what has been the problem in the past — and I’m not just talking about LMPD — is that the selection process excluded those minority groups. To find the best, you have to recruit from all walks of life.”

But Dawson-Edwards thinks “police culture is so strong that even Black officers are stuck in that culture sometimes.” The “for-us-or-against-us” mentality is so entrenched in policing that, she says, “I don’t know that more Black officers is going to change that — unless you get more Black officers who are resistant to that culture.”

For Bottoms, the combination of white officers who have little life experience dealing with Black communities — officers who went to predominantly white schools and live in predominantly white areas — combined with systemic racism can produce troubling results. “The only thing you know is what you see on the news, what you see on TV,” he says of those officers. “And then you get on the police department fresh out of college and you get put down in the West End or Portland or one of these predominantly Black areas. Then the only thing you see — as a patrol officer, you’re making runs (for) basic domestics, assaults, shootings. So this reinforces what you see on TV, the only thing you know about Blacks. And that’s where you get people starting to judge all Blacks the same. ‘All Blacks are criminals, all Blacks are thugs. They’ll fight you. They’ll kill you in a heartbeat if you turn your back on them.’”

In an interview one morning in September, David James sits on his truck bed, parked in the Starbucks parking lot at Third Street and Central Avenue, pausing to say hello to folks he recognizes, including officers. Later that day, Attorney General Daniel Cameron will announce the grand jury’s decision.

“Now, in the year 2020, we have a police department that’s extremely young, and a lot of the officers have not come from an urban area and they have not been talked to about the history of African-Americans and the Louisville Metro Police Department,” he says. “So many of them now when I talk to them, they’re like, ‘Why do people hate me? I just got hired on the police department. I haven’t done anything to anyone.’”

James says he’ll often see white officers in the West End driving with their windows up, while Black officers will keep them down so they can say hi or talk with people as they go by.

“That interaction is important. In African-American culture, being close to people is important. So when officers drive around in their police cars with their window rolled up talking on their cellphone, what you’re really transmitting is: I’m not interested in you, I don’t care about you. Now, that may not be what the officer means to transmit, but that’s how it’s perceived,” he says. “Twenty years from now, when I look at the police department, I want to see officers out here no matter what color they are with the window rolled down and talking to folks and being part of the community.”

This article was originally published in print in December 2020.

Share This Article

We want to hear from you. Who or what should more Louisvillians know about? Share here.