Published February 5, 2021.

By Taylor Killough | Photos by Mickie Winters

Before the women marched in the streets, the reverend told them a story.

“There was a woman named Hagar in the Bible,” she said. “Let me tell you something about the strength of Hagar. Hagar prayed one prayer: ‘Lord, do whatever you want to me, but save my sons.’

“That’s the spirit of a Black woman.”

A few feet away, Shameka Parrish-Wright closed her eyes and thought, Thank you. And then: We’ve got so far to go.

Helicopters ripped through the sky overhead as Shameka Parrish-Wright tossed her long locs behind her shoulder. An answer was coming. And she knew what it would be.

The signs were all there: fences around nearby federal buildings, garbage trucks and concrete barriers blocking intersections, fresh-cut plywood over every window for several blocks — all measures to protect property, stoked by fear of the people in the Square.

The people in the Square had been there, at Sixth and Jefferson streets, for 119 days. They’d cried together: for Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old Black woman shot and killed in her apartment by Louisville police on March 13; for David McAtee, the west Louisville barbecuer killed by a National Guard soldier in June; and for Tyler Gerth, a photographer who was shot and killed at the Square later that month. They’d marched every night, often to neighborhoods miles away, chanting loud enough to wake people up. They’d been hit with tear gas and rubber bullets and arrests. They’d danced, sang and played the piano. Slept in tents, raced each other in the streets. Cooked and ate meals together.

They’d become a family.

On this day — Sept. 23 — they would find out whether or not three Louisville Metro Police Department officers involved in the shooting of Breonna Taylor would be charged for her death.

Under a white tent, “Breeway or the Freeway” hand-written in black marker on the front panel, Parrish-Wright stepped in front of the crowd of hundreds. “Be careful what you do, what you say,” she said, her voice urgent but measured. “It’s like war out here. When they come, they come full force.” Then, the most important part: “Make sure you take care of one another.”

Through a cell phone held to the mic, the crowd listened to a faraway voice read the announcement they’d been waiting for: LMPD officer Brett Hankison — whom interim LMPD Chief Robert Schroeder fired in June for “blindly” firing into Taylor’s apartment — received three counts of wanton endangerment in the first degree. The first count was for bullets that flew into an apartment occupied by someone with the initials C.E.; the second count for an apartment occupied by initials C.N.; the third, an apartment occupied by initials Z.F.

“Wanton endangerment?” Parrish-Wright thought as she rummaged through her blue purse with an outline of Africa under the rim. “They’ve charged us with wanton endangerment.” (In addition to Hankison, in early January LMPD fired two more detectives, Myles Cosgrove and Joshua Jaynes, in connection to the shooting of Taylor.)

When the readout finished, Parrish-Wright’s round eyes narrowed, then closed; her mouth squeezed into a tight frown. She shook her head. She’d known an answer was coming, and she’d known it would be this: No justice for the initials B.T.

As people cried out and held one another in disbelief, Parrish-Wright pulled a pair of goggles and a gas mask from her bag, worrying tear gas would soon fill the air.

A tall young woman wiped tears from under her glasses and put her arms around Parrish-Wright.

“It’s not fair,” she cried into Parrish-Wright’s shoulder.

“I know,” Parrish-Wright said. “We knew it was injustice from day one.”

In a county named Jefferson, on a street named Jefferson, in a park named Jefferson — after a president who enslaved hundreds — beat the pulse of what may be the largest racial justice movement in history.

Millions marched across the globe in 2020 to demand justice and reform for victims of police brutality. A sense of urgency grew as incidents of deadly violence flared into the public consciousness: A Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd. A viral video showed two armed white men, one of them a former police officer, gunning down Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia. And here in Louisville, LMPD officers killed a Black woman while they served a no-knock warrant at her apartment. “People all over the world are saying Breonna Taylor’s name,” Parrish-Wright says. “But it’s us that are here all the time.”

During the chaotic first days of protests in late May, Parrish-Wright and other members of the Kentucky Alliance Against Racial and Political Repression saw the pain and anger in the faces of young people screaming at police in the streets. Founded more than 40 years ago by legendary activists — including Anne Braden, Angela Davis, Bob Cunningham and Suzy Post — the alliance focuses on grassroots racial-justice movements. Afraid of losing more young people to police-involved violence, members wanted to find a space where they could help people organize and protest as safely as they could. Late one night, they met at the Carl Braden Memorial Center on West Broadway and made a plan: With the help of anyone willing, they would turn Jefferson Square Park — an acre of dated, unused and mostly defunct public space downtown — into Injustice Square Park.

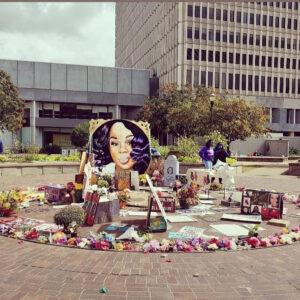

Atop what used to be a circular water fountain, a memorial to Breonna Taylor began to form. People brought flowers, stems stuck in the drain grates. Inside the circle stood a collection of tall white candles and hand-painted signs — “I’m sorry, Breonna”; “KY AG, do the right thing” — all of it anchored by an 8-foot portrait of Taylor painted by artist Aron Conaway, Taylor’s black hair shining purple in places, lips slightly parted in a smile, like she’s always just about to say something.

Occupying this particular space was intentional. At the Square, city leaders couldn’t look away from Taylor’s face or the protesters’ pain: Metro Hall is just across Jefferson Street, the Hall of Justice across Sixth Street and the Louisville Metro Department of Corrections diagonally across Sixth and Liberty. “To be right here, planted in the middle of this city, is both beautiful and dangerous,” Parrish-Wright says. “We brought the fight to their doorsteps.”

If occupying the Square was an act of protest, the way it operated was a form of justice: Everything was free. Leadership was decentralized. Everyone was welcome and anyone could contribute. It was about protest, policy and organizing, but also about food, community and joy.

Thousands visited the Square, many from around the country and the world, but a few dozen people kept it occupied and running all the time. Like Chaunda Lee, who packed her white van with hundreds of pounds of donated food. Sometimes she brought her two teenage daughters, Myangel and Jayla, who were baptized by Mama Gina, a minister who held Sunday service every other week in the summer, filling her tub at a nearby fire hydrant. Paul Gardner, one of a rotating cast of chefs, came to the Square around midday after his morning chemotherapy treatments. A man called Hop Along livened up the mood by taking off his prosthetic leg and playfully pretending to hit his friends with it. The “Clean Up Guy” came by every few days, his own yellow-bristled broom in hand, sweeping away dust, hay and cigarette butts.

With donated food from local restaurants and grocery stores, the people in the Square served thousands of free meals. An organization called Breonna’s Roots planted sunflowers, herbs and vegetables in the concrete planters, free to anyone who wanted fresh produce. Therapists for Protester Wellness offered services to anyone in need. Other activist groups provided medical services and security, and the 502 Live Streamers filmed it all.

To Parrish-Wright, the Square was a microcosm of a more just world, where they fought for justice — not only for Breonna Taylor, but for anyone in need of resources. “We’re here providing what the city can’t or won’t.” Parrish-Wright says. “We got us. That’s what we’ve been saying all along.”

As Injustice Square grew, it became clear to Parrish-Wright that she would help lead it, even if that wasn’t her original intention. At 44, she’s what she calls “seasoned” — experienced in social justice work, though she’s typically more behind the scenes. “She is kind of the people’s Olivia Pope,” says State Rep. Attica Scott, referring to Kerry Washington’s character on the television show Scandal. “She’s a fixer.”

Rep. Scott and Parrish-Wright met 16 years ago, shortly after Parrish-Wright had moved to Louisville from Cincinnati. “She just cares deeply and loves tremendously and she gives of her whole self,” Scott says. “People call me the Shameka Whisperer because I’m one of the few people who can say, ‘OK, Shameka, did you eat? Did you drink some water? How many hours of sleep did you get? Do you need to take a nap? When was the last time you saw your doctor?’” she says. “Her heart is everywhere, but that’s what keeps her heart pumping.”

Parrish-Wright began her organizing career as an intern at the Kentucky Alliance, where she found a mentor in renowned activist and educator Anne Braden, who dedicated herself to the alliance in her later years. (In 1954, Braden, with her husband Carl, purchased a home on behalf of a Black family in segregated Shively, which sparked weeks of racial violence.) Parrish-Wright also took Braden’s class at the University of Louisville. She’d sometimes drive Braden to campus; they’d stand outside together while Braden finished a cigarette before getting in the car. After Parrish-Wright’s internship with the Kentucky Alliance, Braden pushed them to hire her in 2005. “She saw something in me. She used to say to me, ‘You keep waiting for them to pass you the torch. They’re never going to give it to you. You gotta take it, respectably, but take it.’”

In the weeks leading up to Braden’s death in 2006, the two helped to develop an arts-and-activism summer camp. Parrish-Wright says that’s what was on Braden’s mind just before she passed: how to continue the work. “She wouldn’t even let me come to the hospital,” Parrish-Wright says. “She just said, ‘We got work to do.’”

Parrish-Wright continued that work in the decades after her time at the Kentucky Alliance, organizing with Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, doing statewide electoral work with Kentucky Jobs for Justice and serving on too many boards to list here. Parrish-Wright also started her own business helping to coordinate and advise political campaigns for Rep. Scott and judge Annie O’Connell. Eventually, she launched her own campaign for the Jefferson County Public Schools District 4 board seat, which includes southwest Louisville. “People were calling me and saying, ‘Shameka, that’s your district.’ And I realized, ‘I have three kids in the district. This makes sense,’” she says. Though she lost the JCPS appointment to Joe Marshall, she knew she still had an important perspective to contribute to the district. “There’s a lot of missing voices at that table,” she says. “They don’t have a voice like mine.”

In 2018, Parrish-Wright took a job with the Bail Project, a national organization that aims to end cash bail. They work with the group Protest Arrest Jail Support on post-incarceration support: transportation, emergency housing if needed, medical assessment, and filling brown paper bags just outside the jail with snacks, gift cards and sandwiches. At the Bail Project, Parrish-Wright was quickly promoted to Louisville site manager and then operations manager, though her official title doesn’t matter much, according to her Bail Project colleague Savvy Shabazz. “She’s in the field of helping people. That pretty much sums up her job title, period,” he says.

And Shabazz would know. Originally from Paducah, he was released in 2010 after serving five and a half years in correctional facilities across the state. When he was released in Louisville, people in the city helped get him back on his feet. But one woman at a Louisville Showing Up for Racial Justice meeting stood out to him. “Shameka met me with open arms and said, ‘I think you will be a great community organizer. I think you will be a great leader,’” Shabazz says. “I can honestly say that she saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself.”

The Bail Project dovetailed with the work at the Square. Whenever a protester was arrested, Parrish-Wright and her team could track them through the jail system, pay their bail and offer support upon release. Parrish-Wright’s collective years and breadth of experience made her the go-to person for any direct service — transportation, clothing, housing, food.

“It’s way more than just what the Bail Project does. It’s way more than what any specific organization does. When I tell you she does it all, she does it all,” Savvy says.

“It’s just what we do to show up,” Parrish-Wright says. “I’m doing what I would want to be done for me and mine.”

Attica Scott says, “People call me the Shameka Whisperer because I’m one of the few people who can say, ‘OK, Shameka, did you eat? Did you drink some water? How many hours of sleep did you get? Do you need to take a nap?’”

Parrish-Wright learned about Breonna Taylor’s death as many did: on social media. But she heard about it earlier than most.

On March 13 — the same day Taylor was killed — Parrish-Wright was scrolling through Instagram when she saw a post about a woman who had been shot dead by police in her home. One of Parrish-Wright’s daughters, Shamari Parrish, had shared another post: the sister of a high school friend had died. Later than night, Parrish-Wright realized the two posts were about the same woman.

So began what Parrish-Wright’s daughter, Damiona Cure, calls “the strangest game of telephone.” Played out over the Internet, text messages and in-person conversations, new details about Taylor’s death emerged. “Little tidbits kept on coming out,” Cure says. “And it just got bigger and bigger.”

Parrish-Wright had always worried about the safety of her children and had conversations with them about what to do if they were confronted by police. But now she had to worry about them in their own homes? How could she protect them all?

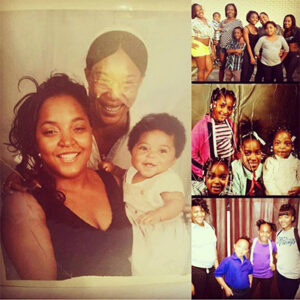

On a night in late April, over plates of steaming pasta on the counter-height square table that’s a little too small for her family, Parrish-Wright sat with all four of her daughters. Shameka, Parrish-Wright’s oldest and her namesake, is 27; Damiona is 24 and just moved back to Louisville; Shamari is 21; and Zacaria, still in high school, was 17 at the time.

“I just can’t help but think that that could be any of y’all,” Parrish-Wright told them. “And that scares me.”

To her daughters, Parrish-Wright is Superwoman. But for the first time, they saw fear in her eyes.

“I want you guys to be careful,” Parrish-Wright said. “It could’ve just as easily been you.”

One warm June evening, Parrish-Wright spotted a woman near the memorial. She was alone, straightening out the signs and flowers around the portrait. Although they’d never met, Parrish-Wright knew who the woman was: Tamika Palmer, Breonna Taylor’s mother.

The last thing Parrish-Wright wanted to do was to bother Palmer at the memorial. So she walked over to the inner ledge of one of the concrete flower beds surrounding it, paying her respects while giving Palmer space. When Palmer was done tidying up, she walked over to the same ledge and sat down a few feet from Parrish-Wright.

“I don’t want to take up too much of your time,” Parrish-Wright said. “I’m going to help hold this up and support the people out here as much as we can. You’re the only one who can shut this down. If you need anything, just let me know.”

Parrish-Wright says Palmer’s reply was simple: “Thank you.”

The two mothers sat together in silence, looking at the memorial.

A few moments later, Parrish-Wright heard someone call her name. Someone is always asking for her help at the Square, and, as she walked away, she looked back at the ledge. Palmer sat alone with the memory of her daughter.

At 8:40 p.m. on Day 120 — the day after the wanton endangerment indictments, the day after Breonna Taylor’s initials were never called — Parrish-Wright tried to pull her car out of the St. Francis High School parking lot before the 9 p.m. curfew imposed by Mayor Fischer went into effect. She and her passengers, including Scott and Scott’s daughter, Ashanti, were heading to the First Unitarian Church on Fourth and York streets, where protesters had taken sanctuary from arrest the previous night. But her car was blocked in by a police vehicle, so they decided to walk.

On the way, others joined them, and soon their group grew to 18 people. They walked down Third Street and, just a few blocks from First Unitarian, ran into a wall of flashing blue and red lights. Wary of crossing the police line, the group changed directions and headed toward a nearby alley. As they walked, Parrish-Wright playfully pointed west, to her office on the 16th floor of the Heyburn Building. “Now look at my watch!” she joked. “It’s only 8:55. We could even go to my office if we wanted.”

They continued around the walkway on the side of the library closest to Fourth Street. Then the group saw them: police, standing at the corner of Fourth and York. Parrish-Wright, at the front of the group, threw her hands in the air. “We’re going to the church!” she said to the officers.

“Where do you want us to go?” Scott asked.

The officers, covered in tactical gear and with weapons drawn, advanced fast and drew a wide circle around the group. “Back up! Get back!”

“We’re going to the church,” Parrish-Wright repeated.

They grabbed her hands, put them behind her back and cinched zip ties around her wrists. An officer told her to sit down. That’s when she started to panic.

Parrish-Wright has what’s called a galloping rhythm of the heart — the right pump of her right ventricle doesn’t work as well as it should. If she sat down with her hands behind her back, especially with her heart pounding, her pacemaker — her third since she was diagnosed at age 29 — could stop working.

She thought about Eric Garner. She thought about George Floyd. She wondered what it would take for the officers to believe she has a heart condition. Would they listen if she told them she couldn’t breathe?

Luckily, they did. They let her lean against a wall while they lined up other members of the group on the curb.

At the jail, two corrections officers — both Black women — checked Parrish-Wright’s vitals and treated a small cut on her wrist from where they cut off the zip ties. Parrish-Wright says one of them said, “I was just at First Unitarian last night, and I heard you speak. You did so well. I appreciate what you’re doing. Please keep going.”

That night, while the rest of the group tried to sleep on the cold jail floor, wrapped in thin blankets, Parrish-Wright paced the cell. Everyone in the group had been charged with failure to disperse, unlawful assembly and first-degree rioting — the latter a Class D felony. She worried about their voting rights. She worried about what was happening at the church — would police try to get in? She worried about Taylor’s memorial at the Square and what would happen if the police tried to take it down. She worried about Scott, alone in a cell by herself, separated because she is an elected official. She worried about how to keep the movement going now that the grand jury had made its decision. “How do we keep people engaged?” she thought. “How do they see that the fight isn’t over?”

She thought about her father, and about the last time she was in jail.

“To be right here, planted in the middle of this city, is both beautiful and dangerous,” Parrish-Wright says.

Parrish-Wright grew up in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood in the 1980s, before the 2001 protests in response to the police shooting death of Timothy Thomas, before shiny new Vine Street and condos that sell for half a million dollars. Her father was in and out of jail, ultimately living 40 of his 56 years incarcerated. She spent her early years with her mother and an abusive stepfather, and remembers early exposure to drugs and alcohol, and visiting family members and friends in the hospital who were dying of heroin overdoses and complications from AIDS. She fantasized about living with her father and missed him when he was away: the feeling of safety she had around him, his bow-legged walk, his eyes that changed from green to gray in the right light. She missed riding around in his green station wagon, watching his afro lie back in the wind.

But that longing was also mixed with resentment. She didn’t understand why he couldn’t stay out of trouble. “I was so angry at him that I didn’t realize when he was trying,” she says. He was stuck in the cycle of poverty and crime: Go to prison. Get out. Sell drugs. Steal. Get caught. Get arrested. Go back.

But he always wrote her letters and stayed connected. As she got older, he started sending her books: Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Assata Shakur and her favorite, Langston Hughes. He wanted her to be street smart, too. Parrish-Wright briefly got her wish when she was 13 and they lived together during the height of the crack epidemic of the ’80s. “He was honest with me about everything,” Parrish-Wright says. “I was seeing so many guys I knew dying, bad drug deals and boyfriends and friends. And he showed me how easy it is to get caught in that life.”

As she learned more about her dad’s time in jail, the target of her ire shifted from what she thought were his personal shortcomings to the systemic problems Black people often face in America, the circumstances he and so many others she knew couldn’t seem to escape. “Things were never pretty,” Parrish-Wright says. “By the time I was pregnant at 15, I didn’t even want to live anymore. I was at a point in my life where I was just like, ‘Is this what life’s about?’”

Parrish-Wright knew she wouldn’t get much help with her baby from her parents. After giving birth to her first daughter, she dropped out of school, became an emancipated teen and worked full-time while taking night classes to get her GED. “I had to be really mature early on,” Parrish-Wright says. “I had to grow up really, really fast.”

By the time she was 18, Parrish-Wright was engaged to be married, but the on-and-off relationship wasn’t going well. One early morning, she says an argument with her fiancé turned physical. She says he ripped the phone out of her townhouse wall. When the police arrived, they asked Parrish-Wright to write down everything that happened. She says she did, including how she’d tried to defend herself.

The police arrested her and charged her with felonious assault, which carries a potential sentence of 14 years in jail. She was given a bond of $10,000 at 10 percent for release. That’s $1,000 neither Parrish-Wright nor her family had. So she stayed in jail for 38 days. During that time, Parrish-Wright couldn’t see her daughter. She agonized over what would happen to her if she had to spend 14 years behind bars. On her court date, the judge offered her a deal: two years’ probation for aggravated assault, a misdemeanor.

“When I got out, I was just like, ‘Never again. I’m not gonna do this to my daughter,’” Parrish-Wright says.

“But if you run my fingerprints, that’s what comes up,” she adds. “It just follows you around, you know?”

The morning after her arrest at Fourth and York, Parrish-Wright walked out of jail in a Black Lives Matter mask with a plastic bag of her belongings, laughing as friends ran up to hug her. Before walking out into the morning sun, Parrish-Wright grabbed one of the Bail Project’s brown paper bags. Inside was the best peanut butter and jelly sandwich she’d ever tasted.

After a sleepless night in jail, Parrish-Wright wanted a shower, some hot food, rest and to see her kids. But she couldn’t go home yet. A press conference was scheduled at the Square, and Tamika Palmer asked her to stay. For more than an hour, people spoke about the grand jury’s decision, their lack of faith in Attorney General Daniel Cameron, and the family’s pain. Parrish-Wright stood at the back of the crowd of speakers and didn’t take the microphone. She just wanted to support Palmer.

By mid-October, Parrish-Wright was tired. She’d forgotten to pay her car note. Her husband, James, was feeling neglected. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d made dinner for her family. She’d spent thousands on DoorDash just to keep her kids fed. The family dog — a big, goofy pit bull named Thor — lay on piles of her clothes while she was gone, looking for any way to get close to her.

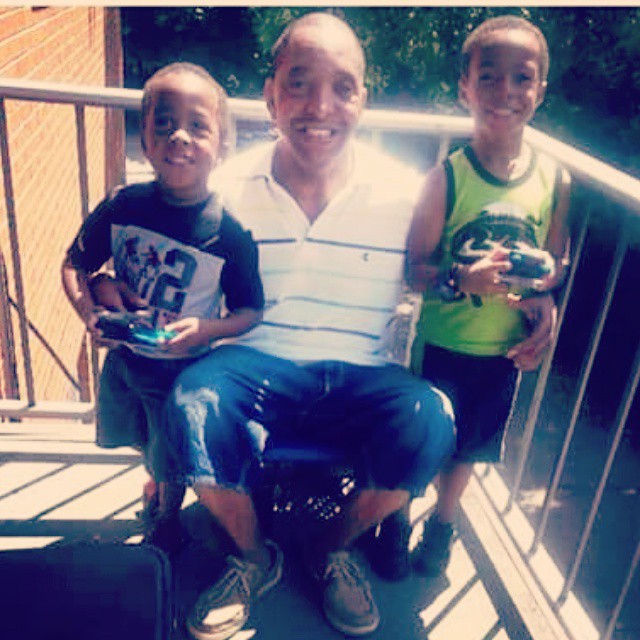

So, on a Sunday, Parrish-Wright gathered everyone at her house. James grilled steaks while Parrish-Wright made her famous green beans with bacon, peppers, chicken broth and onion soup. When people sit down to dinner at Parrish-Wright’s house, everybody’s plates are piled high. All six of Parrish-Wright’s kids were there: her four daughters, two boys — James Jr. and Jaiden, ages 12 and 11 — and her granddaughter, Aiyia’Joy, who’s almost two. Then there’s her grandson, Daejon Lee, a bow-legged boy with eyes that change from green to gray in the right light. Parrish-Wright says he’s like the reincarnation of her father.

In the later years of his life, Parrish-Wright’s father realized he was getting too old to go back to prison. He wanted to be there for Parrish-Wright and her kids. He had a galloping rhythm of the heart too, and in 2015, it caught up with him. He died in his Cincinnati apartment after an asthma attack caused an arrhythmia.

For Parrish-Wright, the fight for justice started with him, but it continues for so many after: for Breonna Taylor, for the little boy with the eyes that change colors, for the young people at the Square, for her four daughters. “This kind of work is hard on personal relationships,” Parrish-Wright says. “People think you don’t care about your family as much, or your family feels like you don’t care about them.”

Parrish-Wright says her daughters understand why she’s gone all the time, and they joined her at the Square when they could. It’s harder on her younger sons. One day, James Jr. said, “Mom, I’m glad you’re there. Next, can you fix the schools?”

“I know they miss me when I’m gone,” Parrish-Wright says. “But they know I’m out there to make sure it isn’t one of our children.”

Before walking out into the morning sun, Parrish-Wright grabbed one of the Bail Project’s brown paper bags. Inside was the best peanut butter and jelly sandwich she’d ever tasted.

In November, the fight for justice for Breonna Taylor continued. But the days were shorter, the weather was colder and people anticipated change. Tamika Palmer was ready for a change, too. She told Parrish-Wright she wanted Taylor’s portrait to be someplace out of the elements, someplace she could go to be alone with her daughter. A few days later, Parrish-Wright woke up in the middle of the night — something she does often — and realized she knew exactly where it should go.

On a Saturday afternoon, people lined up to move the portrait, 164 white tally marks on the back counting their days at the Square. More days than anyone thought they’d need to be there; more days than anyone thought they could last. Joy filled the air. That morning, a Black woman was declared Vice President of the United States, and the heart of Injustice Square found a permanent home on the community’s own terms.

They carried Breonna’s portrait through the downtown streets, New Orleans-style: people played trumpets and drums, and big-band jazz boomed from a black SUV leading the way. Parrish-Wright’s long striped tunic swished as she danced with the crowd, the heels of her black boots stepping to the music on West Main Street in front of Roots 101: African-American Museum, the new home of Taylor’s portrait. “Today we’re celebrating. We’ve got a lot to celebrate,” Parrish-Wright told the crowd. “This is about Breonna, and it’s bigger than Breonna, too.

“I want to pass the mic to Breonna’s family,” Parrish-Wright went on. “It’s the tireless work of everybody out here, but we know they’ve carried the weight of this on their shoulders for far too long.”

Then the two mothers met in front of Taylor’s portrait again. Palmer was quiet as she took the microphone, her daughter’s Vanity Fair cover gripped tightly in her fingers.

“Injustice Square,” Palmer said, “Y’all showed out. I love y’all. Y’all have been amazing. We not going nowhere.” She paused. “I’ll fight to the death if I have to.”

“We got your back!” the crowd yelled.

“This is just the resting place. We still gotta be in the streets. I thank y’all, and I love y’all.”

“Breeway!” the crowd chanted.

Her daughter’s portrait safely at rest, Palmer walked back down Main Street, surrounded by her family. This time, Parrish-Wright stayed with the painting. Then she and the protesters marched west down Main Street, straight into the setting sun, taking a new path back to the Square.

In mid-January, only a few men occupied Injustice Square. A gray tarp covered what was left of Taylor’s memorial. The white tent was fortified to keep out the cold, with colored tarps hanging down its sides. A pile of wood scraps leaned against one of the concrete planters, which were mostly empty except for a few hardy plants. Some of the memorial to Tyler Gerth remained, a white cross sticking out of the dirt.

Parrish-Wright says the movement isn’t over. Says it can’t be. There’s still so much work to do: passing Breonna’s Law, which bans no-knock search warrants, statewide. Building up the Breonna Taylor Foundation. Lobbying to drop charges against protestors.

In response to the announcement that former Atlanta police chief Erika Shields — who resigned when Rayshard Brooks was fatally shot by an Atlanta officer — is LMPD’s new chief, Parrish-Wright makes an announcement of her own: She’s running to be the first Black person and the first woman to be mayor of Louisville.

“I’ve been a part of what it takes to help keep the city from burning,” she says. “As a country, we’re recognizing that Black women’s leadership has always been there; it just hasn’t always been given the light. We can no longer stay in the background.”

Share This Article

We want to hear from you. Who or what should more Louisvillians know about? Share here.