“One of Us”

At the foot of the mountain, a crew from the CBS affiliate in Hazard, WYMT, waits for them. Megan Goble goes home and posts photographs of the dead animals on Facebook. She’s furious, unwilling to spare anyone the gore she witnessed. “I felt like people needed to see,” she says. “If people don’t know this goes on, don’t know the severity of it, nothing is going to happen. And people need to know. They need to get mad. It needs to bother them. It needs to upset them.”

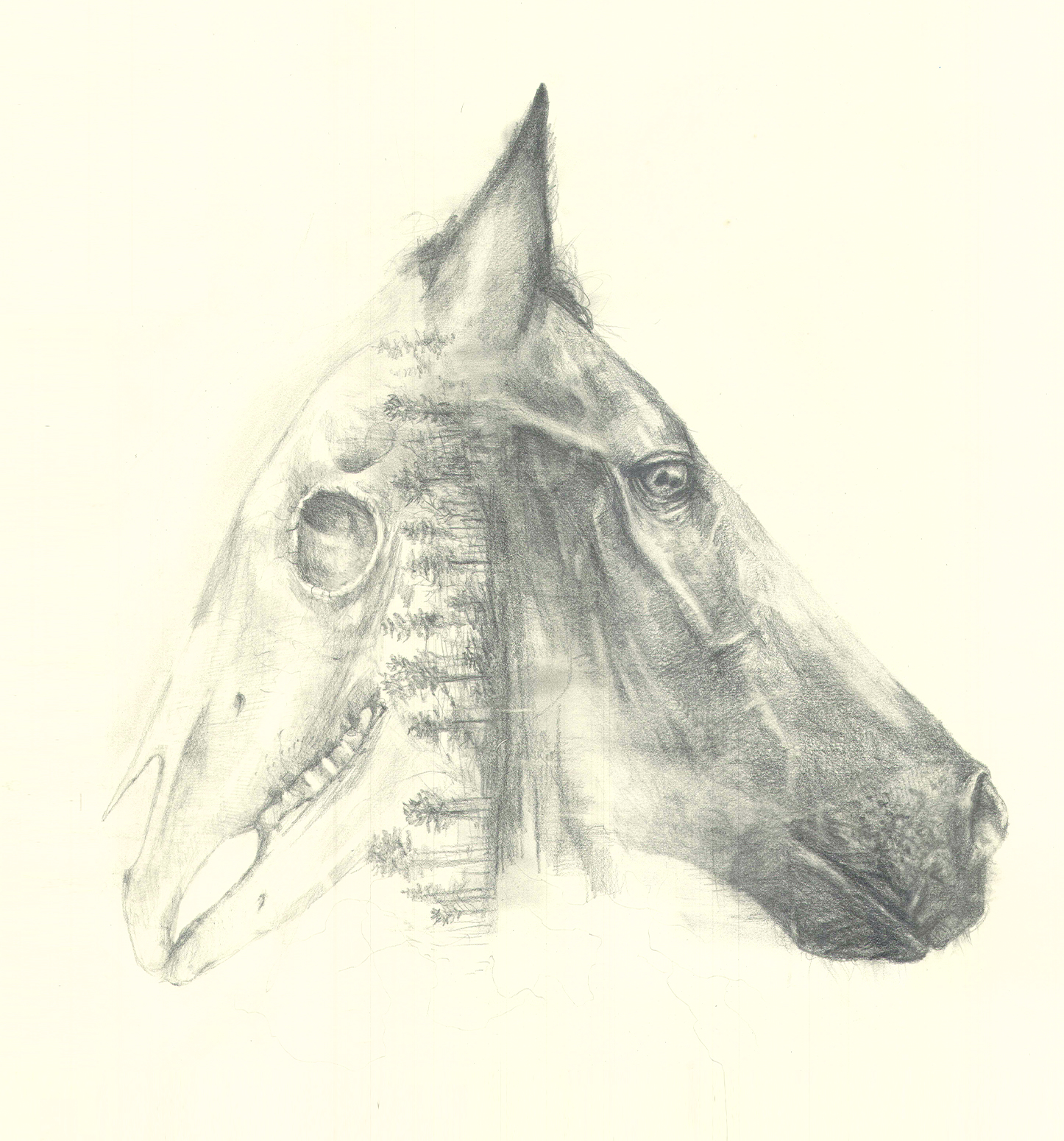

What may be the worst of it: Whoever did this, they know this strip job. This wasn’t a stranger climbing one of the many access roads up the mountain. A stranger would attract attention. This fact eats at the sheriff, this strong possibility that he’s looking at the work of a neighbor. “I hate to think that it’s somebody that grew up in our area,” Hunt says, “that cherished a horse and knew it, and knew our history. It’s a cowardly act, and it’s a defenseless animal.

“And it’s personal, to be honest. It’s personal.”

Megan Goble says, “It wouldn’t shock me a bit if it was somebody that I went to high school with or knew my whole life. It wouldn’t shock me ’cause that’s how close-knit we are. Everybody knows everybody. Everybody knows where you live. Everybody knows who your parents are.” That’s just the way it is in Prestonsburg.

Prestonsburg proper is less than 10 miles from Cow Mountain. On the road between the strip job and downtown stands the memorial to the town’s biggest tragedy, the bus accident that killed 26 elementary and high school students and the driver in 1958 when school bus No. 27 plunged into the flood-swollen Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy River. At the time, it was the worst bus accident in the history of the United States, only to be matched in the state in 1988 by the horrific bus accident in Carrollton caused by a drunken driver.

Like many mountain towns, Prestonsburg is longer than it is wide, its business district snaking like a river, constrained by surrounding topography. There is the usual jumble of chain stores that unite the nation in a ticky-tacky monotony: Walmart, Walgreens, AutoZone, a half-dozen Family Dollars, Dollar Trees and Dollar Generals. Nearly every fast-food franchise is here, and McDonald’s twice, separated by 2.2 miles of highway. You can even buy a Starbucks latte at Food City. But the Floyd County seat of 2,900 souls roughly an hour from West Virginia to the east or Virginia to the south retains a healthy collection of homegrown commerce. Skip both McDonald’s and grab a Smashburger at Dairy Cheer instead. Ignore Taco Bell and settle in at El Azul Grande or El Rodeo Grande. Cold-shoulder Starbucks and zip over to City Perk. Have a nice dinner at the Brick House. Motor to the Cloud Nine Cafe at the airport on a strip job just over the Martin County line. It’s crowded on Sunday afternoon, but if you’re lucky, you may see an elk grazing or an airplane taking off.

It’s hard not to attribute some symbolism to the community’s choice of an icon: a rainbow arch bridge built in 1928. It’s celebrated in murals and signs all over town and etched in white on every city trash barrel. But the bridge itself is now so dilapidated that it’s barred to even pedestrian traffic. Yet Prestonsburg’s downtown is vital, with dress shops, children’s-wear purveyors, a sewing center, a photo studio. You can do yoga in the old post office building and even have your wrinkles smoothed and lips plumped at a downtown aesthetician business. Don’t look here for Mayberry. The town is not trapped in amber. There is no Floyd’s Barbershop; Wright’s barber shop is a butter-colored building with orange and aqua highlights. And Billy Ray’s, with its red upholstered booths, tin ceiling and low lighting is too slick to be the Bluebird Cafe. As in many towns, bored teens spend their evenings driving around listening to music or congregating in a downtown parking lot. What Prestonsburg lacks in adolescent entertainment it makes up for in churches. Even the downtown stores advertise their love for Jesus: “This studio is owned by our Father in heaven I just manage it.” “Fall for Jesus He never leaves.” “Every single holler you go up, I guarantee there’s a church,” Megan Goble says.

When the sheriff’s department announces a road accident on Facebook, at least a dozen people pipe up to say they’re praying. When there’s flooding, people are praying. When there’s a rock fall, people are praying. When the sheriff’s house burned down in December 2020, they prayed again. But more often, the sheriff’s Facebook page is full of drug-bust announcements — fentanyl, heroin, meth, that unholy trinity — week after week after week, the same sad litany accompanied by more prayer and atta-boys for the sheriff.

But to the wider world, the vital little town didn’t exist until Megan Goble started posting photographs on Facebook. And suddenly, everyone was watching. “Within the first hour or two of me posting, my phone did not stop,” she says. “My anxiety was going through the roof because I was like, What have I done? I think I had over a thousand and some shares within the first hour, and it just kept growing and growing and growing and growing, and people kept sending me messages and calling. I had 300 friend requests from people from all over.” In 24 hours, her post had been shared 14,000 times. Journalists from everywhere — Brazil, the United Kingdom, Ireland — were calling Conn, Goble and the sheriff. Within that first 24 hours, there was a $1,500 reward fund created by Megan Goble, Sheena Maynard and the sheriff personally. By noon, the reward rose to $3,000. Four days later, it reached $20,000, with donations from all over the country. It finally peaked at $23,000.

The reward fuels rumors. The sheriff’s department’s phone rings with tips and, from all over the world, encouragement. “Everybody wanted to pitch in and help,” Hunt says. Although some tips are clearly from people hoping for a payday, many more that arrive via the department’s anonymous tip line are sincere. “We checked every tip that came in,” Detective Shepherd says. “At one time, I think every time that phone rang, it was a call about the horses.”

Although this is the worst horse-abuse incident anyone can recall, it’s not the only time strip job horses have been shot. Four years ago, somebody shot three stallions point blank in Martin County just west of Floyd on the West Virginia line. The deaths remain unsolved, but some believe the stallions were shot to keep strip job mares from getting pregnant. “It used to be common knowledge that you wouldn’t put a stud horse on a strip job,” says Joey Collins, the Pikeville large-animal veterinarian who came up to Cow Mountain to perform a field necropsy two days after the Cow Mountain horse slaughter was discovered. It wasn’t a first for him. “I’ve seen things like this,” Collins said. Thirteen years ago, a pair of teenagers killed three horses and injured eight on a strip job near Elkhorn City in Pike County in the far southeast corner of the state, shooting one four-year-old mare 50 times. They simply stood over the mare and unloaded into her. The teenagers pleaded guilty to felony and misdemeanor charges and were each sentenced to six months in jail and ordered to pay $25,000 in restitution. In 2021 there have been at least two more fatal horse shootings, and at least one horse wounded by gunshot.

But why are horses even up on these mountains? Why are strip jobs throughout the eastern half of the state home to growing horse herds, half or more feral? Collins, a vet for 32 years — whose clinic operates on a first-come, first-served basis because people come so far to see him — has watched the herds expand. Fueling that growth, he suggests, is the closing of horse slaughterhouses in the United States in 2007 when Congress essentially banned domestic horse-meat operations. Slaughter plants meant that horses always had market value. They were worth too much to simply let go. The Humane Society of the United States takes a different view. With slaughterhouses still operating in Canada and Mexico, it argues, the number of horses sent to the abattoir hasn’t decreased. It reports that more than 80,000 American horses, most of them healthy, are slaughtered every year. Instead, the organization maintains, horse abandonment is an outgrowth of economic downturns — a rationale that, if you think about it, is close to the one Collins offers. In any event, even without U.S. slaughterhouses, there are occasional stories about horses disappearing from strip jobs, rumored to be taken for slaughter over a border. A federal program that paid people to adopt feral Mustangs out West turned into a direct line to the slaughterhouse for some horses when people used the program for profit, recruiting everyone they knew to adopt animals, which they then sent for slaughter. Further, illegal slaughter operations have been reported in the United States.

Another reason for the growing abandonment problem is the lack of consequences for the owner who walks away from an animal. The practice didn’t start as abandonment; people released their mares and geldings on strip jobs for summer grazing, then brought them home before winter set in. When coal was still king, mining company personnel and some miners would set out hay bales and keep an eye on the animals, says State Sen. Robin Webb, D-Grayson. (Grayson is in Carter County in northeast Kentucky.) “It used to be a pretty symbiotic relationship,” Webb says. But a lot has changed. The mines closed. Some sites went into bond forfeiture or bankruptcy, she said. With mine jobs gone, families couldn’t keep up with the expense of horse ownership. An often-cited University of Maine survey found the average annual cost of owning a single horse is $3,800 — and that’s if you can keep the horse on your own property, the common rural practice. Add another $8,000 or so if the horse must be boarded. Cash-strapped or indifferent horse owners stopped bringing their summer-grazing horses home for the winter. But what turned the brushfire of abandonment into a wildfire of overpopulation was the rampant release of stallions onto the strip jobs with inevitable results. Herds doubled in size, often outstripping the ability of the land to support them. They receive no veterinary care, such as regular vaccination. Sick or injured horses die if no one can intervene, and although these horses will approach people for food, that doesn’t mean they’ll stand still to have a lame foot tended. Oftentimes, people who live near strip jobs will help feed horses and bring them salt blocks rather than see animals starve or wander down to the road to be hit by cars, but that’s at best a temporary solution. Although some view the “wild horses” as tourist attractions, the reality of strip job horses isn’t postcard material. For instance, in 2018-’19, the Kentucky Humane Society, headquartered in Louisville, removed more than 50 horses from the Ruff-N-Tuff strip job 10 miles west of Prestonsburg. Neighbors who tried to protect the animals from starvation and frequent human harassment were overwhelmed by the animals’ needs and human abuse of the free-roaming horses. In some ways, laws work in the abandoner’s favor, making horses difficult to rescue even when they are starving to death. Owners have interrupted more than one rescue.

Sen. Webb along with Sen. Johnny Turner, D-Prestonsburg, proposed the formation of an Abandoned Horses Task Force after the Cow Mountain horses were killed, but the idea gained no traction in the Republican-controlled Senate in 2020. “We didn’t get a hearing or anything. It just laid there,” Webb says. “Of course, it was a strange session. COVID hit, and nothing really got done.” This year, no animal-welfare legislation passed during the abbreviated legislative session in Frankfort. “Stewardship demands the state tackle the problem,” Webb says. “If you’re going to have them out there, you’ve got to manage them. If you’re going to allow them to exist and continue, they need to be managed for their health and the health of other species.”

Conn said a visit this spring to one strip job she declined to identify revealed that conditions are worse than ever. “Even though we had a milder winter here and spring grass has been up for five or six weeks, and we’ve had good growth even at the higher elevations, the yearlings are in extremely bad shape, with dull coats, lethargic, not to mention lice-ridden. They have a heavy, heavy load of engorged ticks already. That leads to anemia when they’re already struggling. They’re not getting enough nutrition nursing on a mother who’s already given all she’s got to the baby in her belly when she didn’t have enough forage. It was just really, really heartbreaking to see that they didn’t gain weight with the spring grass.”

In the meantime, the horses are destroying the ecosystem that mine reclamation was to restore, Conn says. Because a horse, unlike deer, elk, or even cattle, pull up grass by the root, they strip the mountaintop bare. When the grasses are gone, the horses eat the bark off the trees. The lost browse and trees mean deer and elk go hungry and turkeys have nowhere to roost. Turkeys eat the insects that attack deer and elk; their absence leads to deer, elk and horses weakened by parasites.

Abandoned horses may prove a barrier to economic growth as well. Fifty-six horses live on the Martiki strip job in Martin County, Conn said. Edelen Renewables, founded by former Democratic state auditor Adam Edelen, plans to construct some 700,000 solar modules on Martiki, which would produce enough power to light up 33,000 homes, the Lexington Herald-Leader reported. But abandoned horses are a barrier. “Of course the horses are wreaking havoc on the equipment and the construction,” Conn says.

Lori Redmon, president and CEO of the Kentucky Humane Society, says an aerial survey of reclaimed strip mines this winter revealed 743 abandoned horses roaming Eastern Kentucky, but Redmon said the actual number is probably higher. Even though the absence of leaf cover made it possible to improve on an earlier ground-based survey that found 500 horses, Redmon said some horses were very likely hidden by brush, scrub or other barriers.