On March 22, 2021, the City and Regional Magazine Association nominated this story, published in March 2020, for best profile in its national awards competition. I asked the author, Josh Wood, to include a brief follow-up with Vyncex as a postscript. It’s just as wild as I expected.

— Josh Moss, editor

Close your eyes.

It’s the 1890s and Louisville is on top of the world. And here you are: a baron in a baron’s mansion that stands in a sea of barons’ mansions. Yours is a world of stained-glass windows, grand staircases and parlors large enough to host ensembles of the finest musicians. These are the kinds of homes you’d stick a pineapple statue in front of.

Now open your eyes. There’s a bottle of piss on the balcony. There’s a syringe in front of the fireplace. This is no American dream.

It’s autumn, Día de los Muertos, and Louisville has just had its first frost. This is the time of year when abandoned buildings get occupied. People get cold. People get high. People light fires. Buildings burn down. It’s just another part of life on the frontlines of America’s opioid epidemic. At last count, in March 2018, Louisville had about 3,600 vacant or abandoned structures, and it’s believed that a similar number exist today. The city’s Sixth District — which includes this swath of Old Louisville, along with parts of west Louisville, Smoketown and Shelby Park — had more than 600 vacant structures.

People have been trying to get into this Old Louisville mansion, kicking at the doors and prying at the heavy fleur-de-lis window bars. The building’s exterior is brick, but inside has lots of wood. Stripped down to its bones during an aborted renovation a few years ago, it now feels dry and brittle, like your foot could go crashing through the floorboards or a spent cigarette could send the whole thing ablaze. A squatter recently tried to light a fire in the basement, and it feels like a miracle this building is still standing — and perhaps more of a miracle that its intricate stained-glass windows and other architectural flourishes have survived years of neglect. But it also feels like the clock is ticking, like this time capsule might not have survived the winter without an intervention.

But then the pseudonymous photographer Vyncex found the building. He put a new lock on the front door and barricaded access points like he was prepping for a zombie apocalypse: planks of wood secured across windows, other boards nailed to the ground and leaned against doors. The signs warning of cameras and security systems are bluffs. Vyncex has alerted police to a squatter in the basement, and, other than more needles appearing in the sheltered outdoor stairs leading to that basement, the building has been secured. It might survive another winter. “I was just walking through the alleys one day taking photos and hanging out, and I saw a guy and his girlfriend passed out…on the back stairs,” he says. “So I was like, ‘Yo, y’all got to get the fuck out of here, man; my uncle owns this building.’”

His uncle does not own the building. Neighbors say it was being renovated, but construction ceased a few years ago, and the house has since sat stagnant. When Vyncex noticed a door had been kicked in on the grand structure, he saw an opportunity to get inside and take photos — an activity he does in abandoned buildings, or “bandos,” all over Louisville. He thought he’d just be back a few times to shoot, but then he got to thinking: What if he could save the old building and make it into something other than a trap house waiting to burn down? “There are more of these; they’re just sealed up and shit. If they aren’t sealed up, I’ll go seal them up,” he says. “I just don’t want people shooting up dope in them, man.”

The first time I heard of Vyncex I was out drinking with a buddy at Nachbar in Germantown. The May air was hot and heavy, and we were sitting outside because I still smoked back then.

We’d been drinking a bit and the night had grown late as we watched the endless caravan of UPS jets lumber overhead. When we get drinking a bit and one day becomes the next, we sometimes get to telling stories about when we were younger and our lives were more full of adventure and danger — my buddy served as a Marine Corps machine-gunner in Iraq’s Anbar Province and I reported on conflicts and upheavals across the Middle East. I think we were talking about some of my photojournalist friends still overseas who take the kinds of photos that sear into your memory how bad war is and put themselves at great risk doing so. That made my buddy bring up Vyncex. He said he’d been doing some of that how have you not been shot yet? photography in Louisville. He told me to check out his Instagram.

Vyncex’s Instagram is a captivating digest of misery: eroding façades of boarded-up buildings; people strung out on spice; graffiti-tagged drug dens; car crashes; fresh crime scenes; homeless people huddled under overpasses; stories of being held up at gunpoint. And needles. Needles, needles, needles. Needles on Bibles, needles on flags, needles in bandos, needles littering parks. Needles everywhere. He says he calls in needle hotspots to the city’s Department of Health and Wellness. Vyncex says sometimes he’ll rearrange a scene for a still-life shot — like, say, putting a needle on an open Bible — but that he has never planted needles.

Then there’s everything else on his Instagram: rants about photo composition, videos of the leaky ceiling he says his slumlord-landlord refuses to fix, and, of course, memes. Vyncex is perhaps the most prolific maker of Louisville-specific memes, from low-hanging fruit like the unceremonious downfalls of Matt Bevin and “Papa” John Schnatter to mocking the gentrification of Shelby Park and making light of the city’s drug epidemic. Some of the memes incorporate his own photos, like one of Bevin photoshopped into a homeless encampment or the series following “Fenty the Dinosaur” — a tattered stuffed animal Vyncex says he found in an alley behind an abandoned building and named after the potent opioid fentanyl.

Some are funny, some could be deemed offensive (like the one that says “Louisville be like” and shows a fumigation truck labeled “Narcan”). Louisville is often the punchline, cast as a city overrun with drugs, violence, homelessness and corruption.

There are some things I should mention before we go any further.

The first: Vyncex counts Louisville son Hunter S. Thompson as an inspiration.

Chuck Palahniuk’s novel Fight Club is another.

Both involve very unreliable narrators.

I ask Vyncex about this during our first meeting. Is he an unreliable narrator? There is, after all, a fantastic element to some of his stories (like successfully refusing to give up his camera during a gunpoint robbery), and he’s often at the right (or wrong) place at the right time (like when he says he saw a drive-by shooting aimed at a homeless person, and he hit the dirt taking photos). Not to mention he takes pride in trolling, or shitposting.

“It’s just kind of fun at this point,” he says of the content he posts on social media. “Like 80 percent of it is true.” After two months of interviews, he says, “Maybe 13 percent of what I’ve said to you is completely made up.”

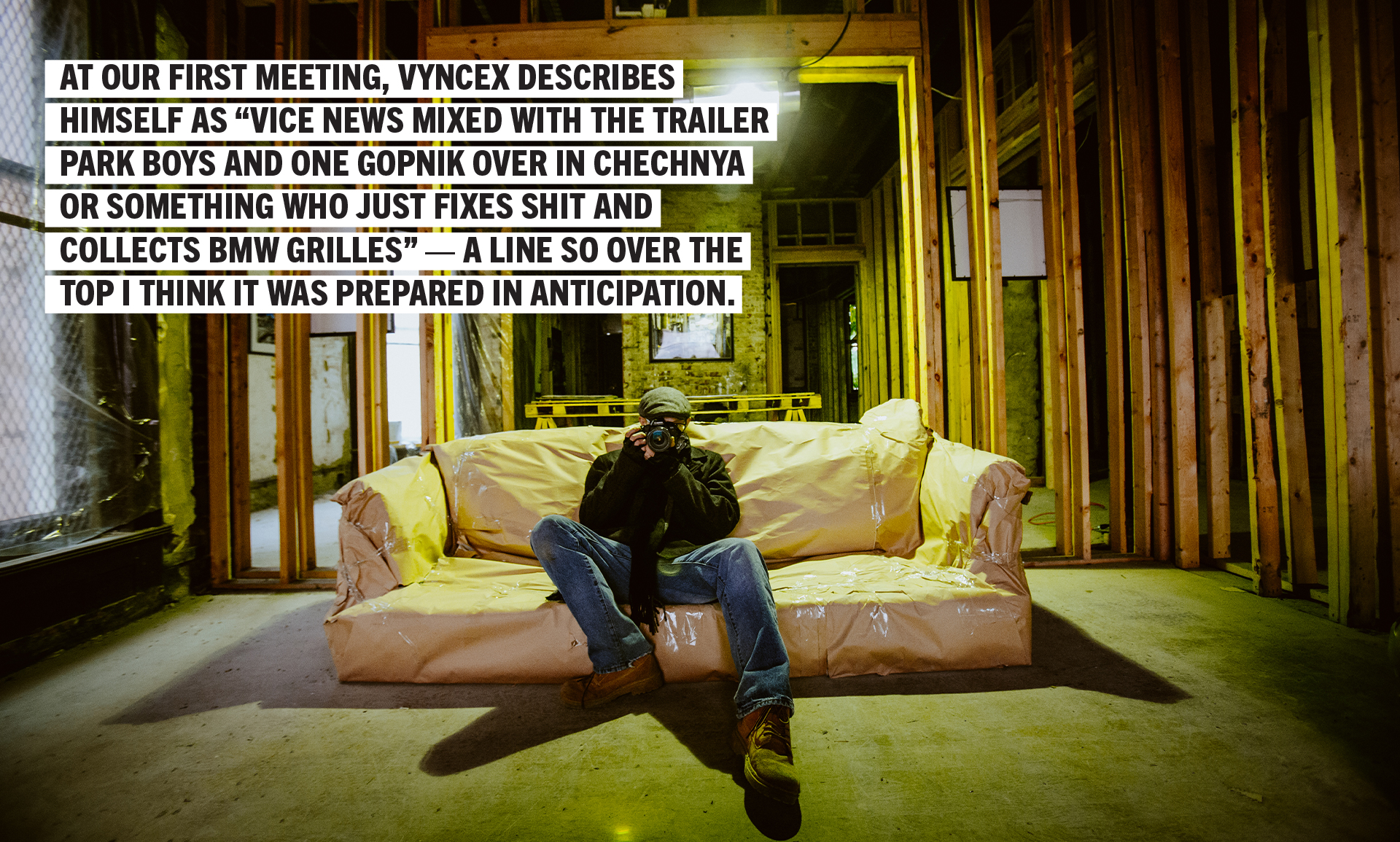

I’m thinking of unreliable narrators as I pull up in front of the address Vyncex texted me.

Online, he’s been talking about claiming a grand old building for himself and waxing on about squatters’ rights. He says he’s going to fix up the building, try to restore it to its former glory. But I have my doubts as to whether the place actually exists. I mostly expect he’s just found a building that’s easy to access and isn’t otherwise occupied.

I call his number and a robot tells me Google Voice is connecting the call.

A minute later, the door swings open. Vyncex reaches out his hand and introduces himself. He’s skinny with a sharp nose, glasses and a beard, wearing a flannel shirt, old jeans and boots, a beanie pulled over a receding hairline. We’re dressed pretty similarly, except he’s wearing tactical-looking fingerless gloves and I’ve got on a Bats cap. At first glance I guess he’s 30ish, though his online persona made me think he was younger. It smells like weed inside.

Framed copies of his prints hang on exposed wall studs. Brown packing paper wraps a couch. Pigeon shit stains some blueprints. Tools are lying around, as are crushed Olde English tallboys and pieces of insulation that a squatter had torn from the wall and used as a bed. The back room has a massive “Matt Bevin for Governor” sign Vyncex says he stole in the Portland neighborhood and a print of a Ralph Steadman drawing of Hunter S. Thompson. He clearly has some control over this space.

He gives me a tour through the 6,000-square-foot house. Whoever stripped down the building left in place the ornate fireplace covers, built-in mirrors and other artifacts that look like they belong in a museum. It’s hard to imagine what the original inhabitants would have made of the scene. “I don’t believe in ghosts, but whoever bought this building, if they died in it, they’re probably haunting the shit out of it,” Vyncex says. “It’s 2019 and your mansion’s gutted and there’s just somebody shooting up ‘fentanyl light’ up there, drinking malt liquor.”

We head outside, into the back. Vyncex has been cleaning up this area, trying to make it look occupied or at least maintained, but refuse still collects from people camping out. On the concrete stairs leading to the basement, he motions to a syringe with his boot. “Oh, cool, a heroin needle,” he says. “Someone really brazenly sat here and shot up dope on these stairs again?”

I’m a little anxious about what we’re going to encounter in the basement. This door isn’t secured like the rest of the building, and the needle shows somebody was here recently. I ask him if he has ever walked into a vacant building that had people inside of it. He says he has but tries not to these days.

In a flash he unfurls a baton he has pulled from his pocket and strikes the door with loud clangs. BANG, BANG! “Code enforcement!” BANG!

He opens the door with a can of pepper spray in his hand. Later, he’ll show me a pistol tucked into the back of his jeans. He tells me he doesn’t like weapons but that they’re a necessary precaution.

The dark basement could be the setting of a slasher flick. An old HVAC unit is a makeshift altar, holding a Virgin Mary statue surrounded by wrappers for the drug spice. Trash and pieces of old wood cover the ground, as does one of those ubiquitous piles of clothes and blankets you see under bridges. It’s the kind of thing you pass every day in Louisville, but here in the dark basement, it feels personal. Someone was squatting here, in a space so cluttered with debris it’s hard to find the floor. Living doesn’t get much rougher.

Vyncex hopes he can do something with the building. “I just don’t see any reason not to use the remnants of this Gilded Age fucking façade of someone’s wealth,” he says. “It’s just sitting here. It’s a shell of wealth and privilege two or three times over. And now it’s just a massive fuck-you to all the homeless people. This hulk of a goddamn useless, worthless building that has people tryna shoot up dope and shit and come in here is being unused while there’s somebody freezing their ass off just down the street.”

Vyncex’s vision is grand and always evolving: If he can fix the place up, he would live there. He floats the idea of setting up an artist colony, a place where starving artists like himself can stay for free or cheap and have studio space — something like a squatter version of Germantown’s Lava House before that burned down in 2008. (Under Kentucky law, squatters can take control of a property through “adverse possession” after 15 years of occupying it. Until then, however, they have no legal claim and can be considered trespassers.)

What stays steady in his vision is this: He wants a studio where he can create and a gallery for events. “I think it’s kind of like an exercise in public anarchy or some shit, just like reclaiming property that’s not being used. Because it was a public nuisance, man,” he says. “Somebody was totally going to come through here this winter and set this motherfucker on fire. I guarantee it.”